Old Friends: The Promise of Parasitic Worms

Alex Loukas, a parasitologist at the Australian Institute of Tropical Health & Medicine at James Cook University, recently studied a video taken during an endoscopy of a patient diagnosed with celiac disease — an autoimmune disorder in which, among other things, the ingestion of gluten can cause severe damage to the digestive system. Where Loukas expected to see aggravated tissue, however, he instead saw pockets of harmony — most of it centered around a pair of centimeter-sized worms embedded in a section of the patient’s small intestine.

“It’s remarkable how little inflammation is around these two worms sitting there eating happily,” Loukas said.

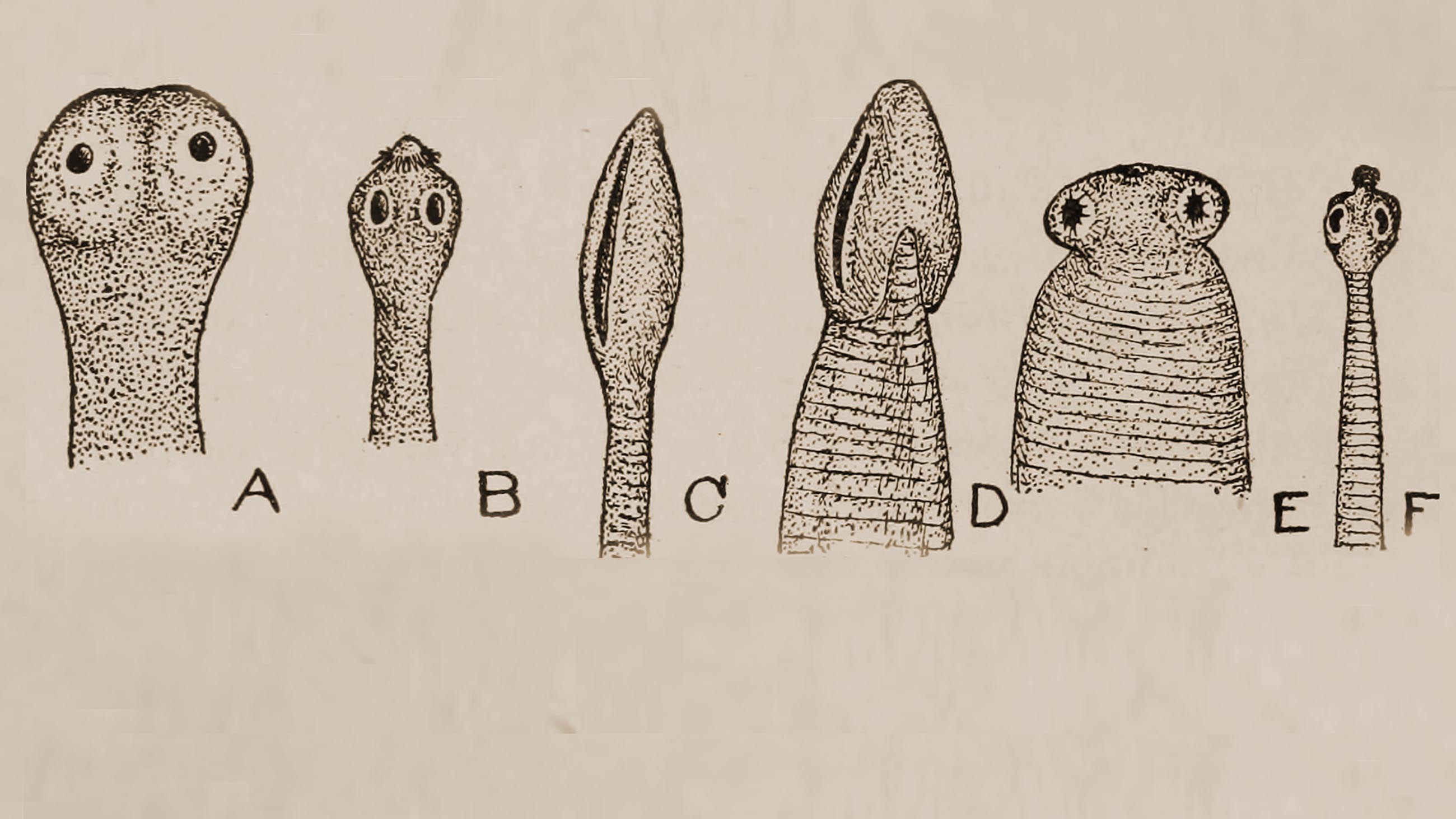

The hookworm Necator americanus seemed to emanate a “be cool” vibe on the inflamed intestines of patients.

Visual: Jasper Lawrence/CC

The patient in the video had volunteered to be infected with Necator americanus, a species of hookworm, as part of a small trial to study the parasite’s impact on celiac disease symptoms. Just as he could see no visible inflammation accompanying the worms’ presence, the study also appeared to confirm that, on a molecular-level, the worms were sending out something of a “be cool” vibe, coaxing the body to decrease inflammatory immune cells, even in the presence of gluten.

Loukas is among a persistent group of scientists who believe deeply in — and are working hard to confirm — the lost magic of parasitic worms, collectively known as helminths. The worms, the thinking goes, evolved as opportunistic free-riders, living and thriving over millennia inside the blood and guts of a variety of mammalian species, including humans. In order to survive in such environments, helminths, which can include any of a variety of flukes, tapeworms, and nematodes, developed adaptations precisely along the lines of what Loukas observed — including an uncanny ability to manipulate human immune system responses. The researchers’ hope is that this characteristic might somehow be exploited to manage any number of common but difficult to treat inflammatory diseases, from disorders of the bowel to asthma and multiple sclerosis.

And yet, while animal and small human-subject trials have shown some promise over the last decade or so — including one led by New York University and published in the journal Science in April — large-scale research into helminth therapy has been slow, sparse, and marred by setbacks. This includes a recent double-blind study involving hundreds of patients that showed the worms to be no better than a placebo.

Meanwhile, a growing number of desperate patients are proving unwilling to wait for more positive results. Even as intestinal parasites remain a dire public health problem in many poor countries, thousands of people worldwide are now navigating a furtive matrix of gray markets and online bulletin boards to learn about, acquire, and intentionally infect themselves with parasitic worms.

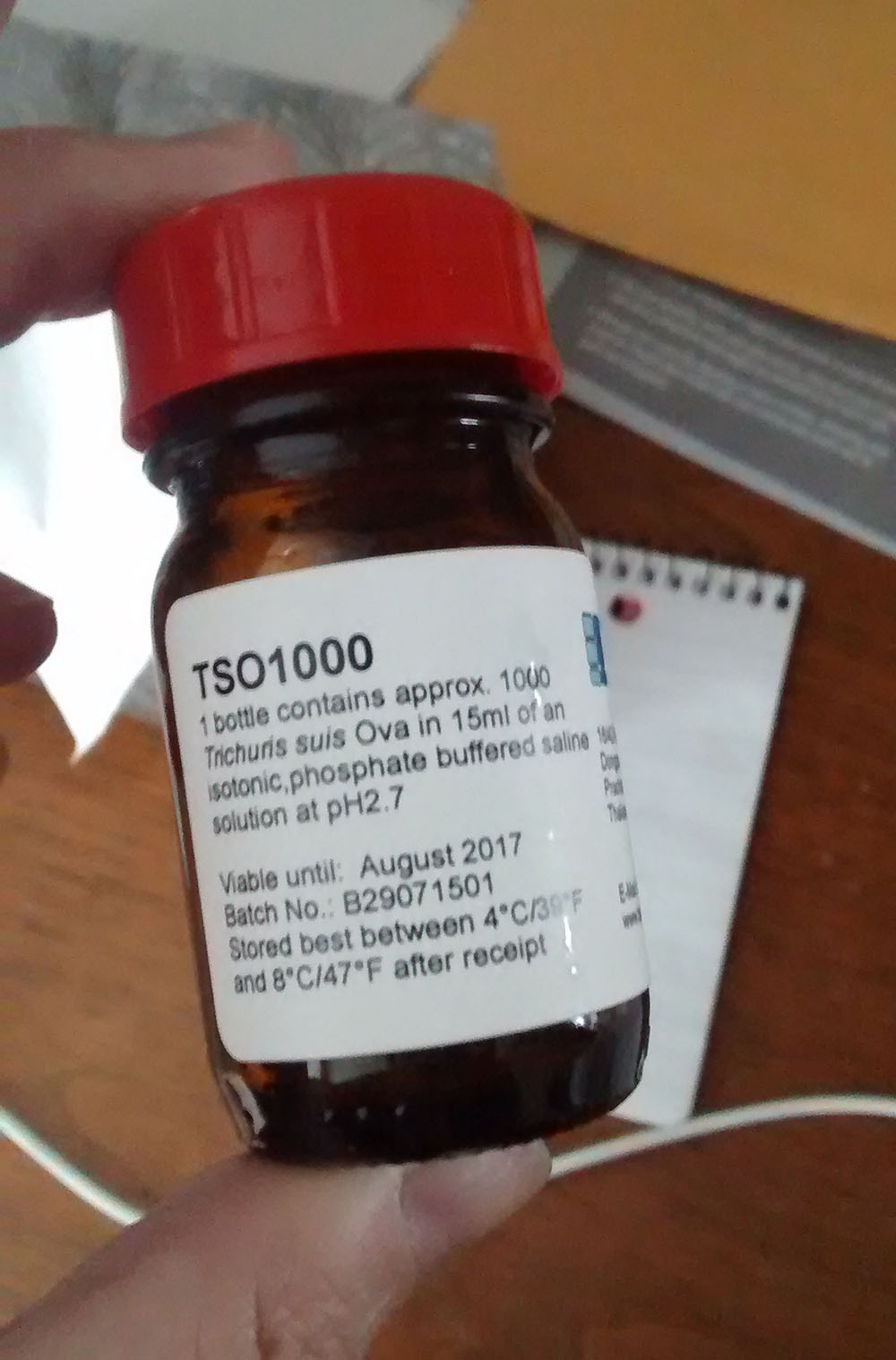

I, too, am a helminth hacker. I have used a type of pig whipworm egg called Trichuris suis ova (TSO) to help treat my ulcerative colitis, an inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD. Every two weeks, I would drink a small glass full of a salty liquid laced with 2,500 TSO, which are designed to hatch and take up brief residence at the juncture of my small and large intestines. I ordered the worm eggs from a company based in Thailand. They cost about $1,500 for a three-month dose.

I cannot say if these worm eggs, or even the worms, are truly effective. I take other anti-inflammatory medications, and my disease symptoms have variably waxed and waned over the course of my helminth treatment. Complicating matters is the fact that inflammatory bowel disease itself is unique to each individual: A wide array of environmental and genetic factors mean that the disorder, and any arsenal of potential treatments, will impact each patient a bit differently.

I also have seen nothing to convince me that I or anyone will find parasitic worms at the local drugstore anytime soon — though researchers might one day isolate and synthesize the still mysterious molecular mechanism that allows some worms to apparently calm tormented bowels.

All I really know is this: Our relationship with parasites is very old, and it is very complicated.

When someone is diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease, a catchall term that typically includes both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, they are being indoctrinated into what remains one of modern medicine’s enduring mysteries. While previous suspected causes like diet and stress have been ruled out, and ample evidence suggests that, as with celiac disease, some sort of immune response dysfunction is to blame, no one really knows — yet — what causes IBD.

Along the same lines, effective treatments involve what can be, for the patient, a frustrating battery of hit-or-miss options. After diagnosis, IBD sufferers normally start out with drugs like mesalamine, a powerful anti-inflammatory, taken orally or as a rectal suppository, to keep the full complement of diarrhea, pain, fatigue and weight loss in check. If those don’t work, doctors sometimes recommend corticosteroids to tamp down the immune response. Steroids, of course, have nasty side effects, especially if used long term, so doctors prefer to use other drugs to keep patients in remission.

If anti-inflammatory drugs don’t work, doctors usually recommend what’s called a “tumor necrosis factor-alpha,” or TNF-alpha, inhibitor. These work by suppressing the function of the TNF-alpha cytokine, a cell-signaler that promotes inflammation and cell death in the intestinal lining. In clinical trials for the TNF-alpha inhibitor infliximab (known by the brand name Remicade), between 20 and 25 percent of participants achieved steroid-free remission after 30 weeks. That’s not bad, but it’s by no means a miracle drug.

If none of this works, patients can elect for surgery to remove parts or all of the colon, which can give them a longer stint of remission.

No one knows the precise numbers, but IBD affects at least 3.5 million people globally, including a million Americans and 2.5 million in Europe. The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America estimates that somewhere between 23 and 45 percent of people with ulcerative colitis, and as many as 75 percent of people with Crohn’s disease require surgery. “Some people with these conditions have the option to choose surgery,” the foundation notes on its website, “while for others, surgery is an absolute necessity due to complications of their disease.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America estimates that hundreds of thousands of sufferers face surgery to address their conditions.

These grim prospects are at least partly responsible for the intense interest among both patients and researchers in helminth therapy.

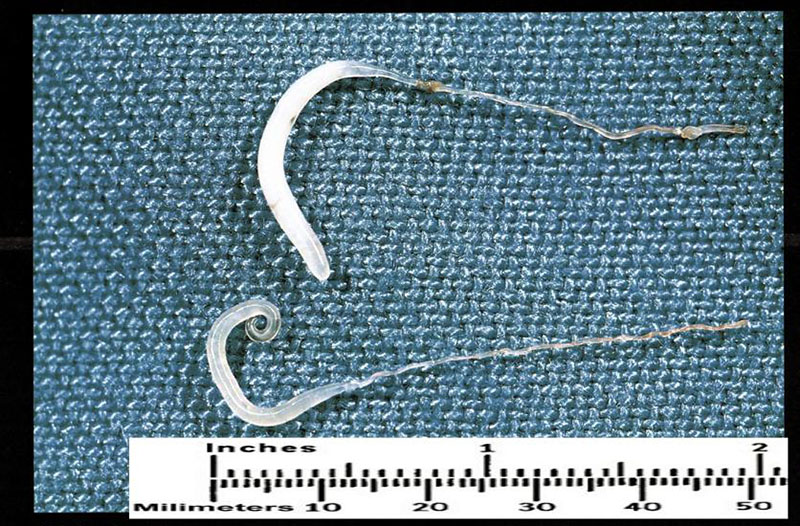

Parasitic worms mostly infect humans through contaminated soil, although different worms have different life cycles. Hookworms, for example — among the most common parasitic infections in the developing world — first start life as microscopic eggs that are shed in stool, then become larvae that, under unhygienic conditions, can penetrate human skin. Once inside the body, the larvae, which are just over half a millimeter in length, eventually settle and mature in the small intestine, where they can live for one to two years. In contrast, the blood fluke, a type of parasitic flatworm, spends part of its maturation in snails. At a later larval stage, it can also penetrate mammalian hosts — including humans — directly through the skin.

Whipworms, meanwhile can only infect humans if the eggs are swallowed, after which they end up maturing in the intestines.

Although the human body evolved with a variety of these parasites onboard, the rich world has spent the last century assiduously eliminating them. That was, of course, for good reason: Even today, at least 1.5 billion people are plagued by parasitic worm infections that, left untreated and uncontrolled, are a public health menace that shaves years off their lives. Blood flukes, for example, infect as many as 200 million people worldwide, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers Schistosomiasis — the disease they cause — “second only to malaria as the most devastating parasitic disease.”

And yet, as the industrializing world dewormed and sanitized the day-to-day lives of its citizens, scientists began to notice a trend: increasing rates of a variety of autoimmune disorders and allergies. The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease, for example, is far higher in developed nations than in emerging economies. And as immigrant groups have migrated from developing nations to industrialized ones, researchers have documented increased incidence of IBD among those incoming groups.

Many scientists now attribute these correlations to what’s known as the “old friends hypothesis” — the idea that, because our bodies evolved with a diverse mix of microbes, parasites, and pathogens, our immune system has also adapted to, and perhaps even in some cases benefited from them. This doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone needs intestinal worms. Autoimmune problems likely arise from myriad circumstances, with a mix of genes, viruses, and a host of other unknown environmental factors playing a role. But it’s possible that some people derive a particular and long-evolved benefit from the worms — or at least the molecular influence they have on our bowels.

To researchers exploring helminths, this suggests that the human-worm relationship might sometimes be something other than one-way and purely parasitic — and even potentially mutualistic and symbiotic. We host them, and, like the best of frenemies, they help us by keeping our immune system from attacking itself.

“Worms,” says Joel Weinstock, a gastroenterologist with the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at Tufts University and a pioneer in the field of helminth therapy, “used to be a universal partner with the human race.”

He set about bringing those partners back together.

In the mid-1990s, Weinstock was making a name for himself — along with colleagues and fellow gastroenterologists Robert Summers and David Elliott — at the University of Iowa, where the team was spearheading research into helminths as a treatment for IBD. The scientists already knew that helminths had unique and powerful interactions with their hosts — including the ability to dampen immune responses — and they wanted to test whether certain benign worms could be used to control the disease’s often intractable suit of symptoms.

They focused their efforts on pig whipworms at the suggestion of U.S. Department of Agriculture microbiologist Joseph Urban. Urban, an expert in swine parasites and mucosal pathogens, knew of a study in which some “adventurous” parasitologists reported that they had infected themselves with the pig whipworm to study its lifecycle. They’d found that the worm egg didn’t live long in humans, nor get a chance to mature and shed out.

Those were precisely the characteristics that the Iowa scientists were after, so they began cultivating the eggs using special, pathogen-free pigs as hosts. The animals were carefully raised in a controlled environment, examined by microbiologists and veterinarians, and prior to use were given anti-helminth treatments to make sure there were no other parasites in place. At that point, the pigs were infected with the TSO, and began shedding eggs about 100 days later.

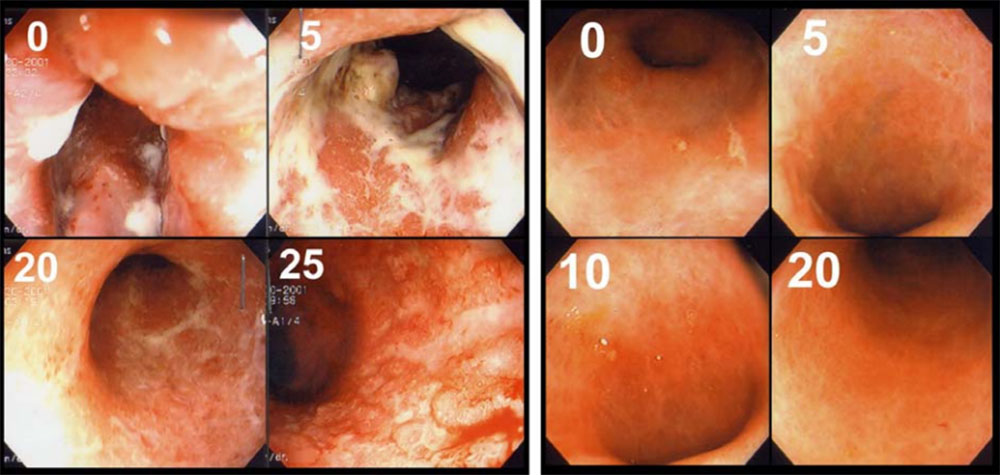

By all accounts, the eggs were a success — at least in some small safety trials. Six out of seven patients with Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis achieved remission from their disease symptoms in the first open safety trial, the results of which were published in 2003. In a study a few years later with 54 patients with ulcerative colitis — randomized, double blind, and placebo-controlled — 43 percent saw improvement in their disease symptoms compared to 16 percent on placebo.

Weinstock’s success eventually drew the attention of Detlev Goj, a German entrepreneur who already had plenty of experience selling uncharismatic minifauna to the masses. Goj had first entered the drug business by starting a company that developed a treatment for wound care using the blowfly maggot — today a therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Goj says he wanted to find more examples of living organisms as healers.

“I was very confident,” he said, “that there must be much more out there in nature that we could convert and use in modern medicine.”

Goj contacted Weinstock and his team, and by 2003, he had sold his blowfly company and launched a new business, first called Biocure, and later renamed Ovamed, in the Hamburg suburb of Barsbüttel. Goj licensed the TSO production methods pioneered by the Iowa researchers — “You cannot do it on your own at home,” he told me — and in 2011, the company partnered with drug companies in Europe and in the United States to conduct a Phase II double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the treatment involving 470 Crohn’s disease patients. The German drug conglomerate Dr. Falk Pharma headed up the trial of 250 patients in Europe, and New York-based Fortress Biotech (then called Coronado Biosciences) ran its end of the study with 220 patients in the United States.

Anticipation was high, but three years later, all future plans for TSO research were scrapped following disappointing — and unpublished — results of the Crohn’s disease trials. Patients had been given either 250-, 2500-, 7,500-egg doses, or a placebo, every two weeks for 10 weeks. But, none showed significant improvement compared to the placebo, according to an abstract presented during a European gastroenterology conference in 2014.

The lack of improvement in symptoms was notable, and Goj and others scrambled to explain it.

Speaking to the biotech business website Fierce Biotech in 2013, Coronado executives suggested that positive results in the study were, in part, diluted by an unusually high placebo response rate. Goj, meanwhile, blamed project planners at Dr. Falk Pharma, who he claims insisted on changing the pH value of the solution in which the eggs were stored. In the original TSO studies — and in the TSO he continues to sell today — eggs are stored in a solution with a pH value of 2.7 and no preservative. His partners in the TSO study wanted to increase the pH to 5 and add preservatives. This could have made the eggs ineffective, Goj speculates.

Dr. Falk’s research and development head Roland Greinwald declined to comment on the pH used for the study, citing confidentiality obligations, but in an emailed response stated: “The potency assays used to monitor the quality of the eggs were within the specification and did not indicate any problem with regard to quality of the eggs.”

Whatever went wrong, the impacts of the failed trial have been widespread, and Weinstock is among many helminth researchers who believe it has helped to stymie or slow helminth studies elsewhere. Companies don’t often go back and repeat trials, says Weinstock, referring to the Crohn’s trial, which he was not affiliated with. “They walk away from it,” he said. “And that kind of poisoned the well.”

Indeed, as the Dr. Falk/Fortress Biotech trial imploded, Bana Jabri, a professor of medicine and pathology at the University of Chicago completing her own Phase II clinical trial of TSO on ulcerative colitis patients, says she started to see her supply of TSO, provided by Coronado, shrivel. “We got patients enrolled and the study was stopped before it was programmed to stop because of the decision from the company,” she says.

Professor Bana Jabri of the University of Chicago saw her supply of TSO diminish. Here, she discusses the role of the microbiome in regulating various human immune responses.

Jabri says her research was structured differently from the Crohn’s trials in that her study attempts to understand how the eggs work on a mechanistic level. To that end, colitis patients offer a unique opportunity to test both inflamed and uninflamed tissue, she says. A typical ulcerative colitis patient has a “line of demarcation” in their colon, below which is inflamed and above is the non-inflamed region. For her study, she took samples of the inflamed and non-inflamed region before and after treatment with TSO, she says. By getting samples of non-inflamed tissue, any changes seen there are independent from inflammation and strictly linked to receiving the worms, Jabri adds.

The Chicago team did not have enough placebo and non-placebo treated patients to make any definitive statements, but longitudinal samples where patients serve as their own controls still may provide insight into how TSO treatment works.

Jabri hopes to publish her results early next year, but most helminth research, including Weinstock’s, is now focused on trying to mimic the anti-inflammatory effects of worms through the discovery of worm products that mediate these effects or through the development of a synthesized drug that mimics the worm products, as opposed to treating with worms themselves. “Going forward, I think it is less likely that the pharmaceutical industry will invest in running more clinical trials using live worms,” Weinstock wrote in an email. “Rather, it is highly likely they will be interested in trials using molecules that will simulate the approach that worms take to mediate host immune modulation.”

William Parker, an associate professor of surgery at Duke University, who has studied gut inflammation and helminth therapy, thinks that will prove too difficult.

“We need to get it to the point where everyone has access to helminths,” Parker says, adding that the worms should be treated almost like a vaccination, given to mothers and children, once they’ve been weaned.

That’s a contentious idea, but as Parker sees it, helminths might be able to prime a child’s immune system for life, so they’d never end up developing a wide variety of autoimmune problems in the first place. Parker, for example, is studying a helminth that would be easy to make available at medical centers, much like fecal transplants are available today. He hopes a wide range of medical centers will become interested in that helminth (called HD, for Hymenolepis diminuta) and plans to “make whatever technology we have ‘open access.’”

But Parker also acknowledges the cultural barriers he will face. Amid relentless clouds of anti-scientific suspicion, it has proved hard enough in recent years to convince many parents of the importance of vaccinations. Still, he says if helminths prove to work they’re thought to, he doesn’t foresee big problems. “After all,” he says, “various assortments of germs (marketed as ‘probiotics’) are very popular these days. It’s all in the marketing.”

The fact that helminth therapy isn’t mainstream isn’t the fault of regulation, Parker adds. Rather it’s a problem with the culture of modern medical science itself. “It’s like a bunch of scientists standing around looking at a fish out of water, waiting till he gets sick, and then we’re going to figure out how we’re going to fix him with chemicals,” Parker says. “It doesn’t make any sense, but that’s the dark side of modern medicine, right there. Because we’re not looking for water to put in the fish tank.”

It’s that sort of lament, issued by scientists who, like Parker, have genuine pedigree and reputation, that have helped to fuel an underground trade in helminths, even as clinical trials falter.

Parker and others published a survey of “self-treaters” that estimates the total population of helminth hackers to be somewhere between 6,000 and 7,000 worldwide. According to his survey, the primary species of worm being used is TSO, followed by human hookworm (Necator americanus, or NA), human whipworm eggs, (Trichuris trichiura ova or TTO) and the larvae of the rat tapeworm (Hymenolepis diminuta cysticercoids, or HDC). In laying out the future for helminth therapy, the study’s authors note that to try to set up clinical trials for all variety and multiple types of helminths could be “untenable.”

“In contrast, one might envision testing different helminth formulations much as chefs test various recipes,” the authors added. “Indeed, this is essentially how the field of self-treatment with helminths has advanced.”

Such advances, if they can legitimately be called that, have unfolded sporadically, in large part because the market for helminths is regulated in wildly different ways, depending on the country. In the U.S., unless they are approved as an investigational new drug, or IND, for a study, helminths are subject to an import alert from the FDA. This means that if customs finds packages containing helminths without an IND permit, they’ll be confiscated.

The FDA declined to answer questions about the status of helminth regulation in the U.S., but a press officer from the agency pointed to the import alert, issued by the FDA in March, that outlines the agency’s concerns. From that alert:

Hookworms, Whipworms, Tapeworms, and their eggs, and larvae used as immunomodulators to treat patients with allergies, asthma, autism, Crohn’s Disease, multiple sclerosis, Sjorgren’s Syndrome, and Ulcerative Colitis by deliberate self infestation are considered to be biological products as defined in Section 351 of the Public Health Service Act. … FDA has concerns regarding the product’s safety as the Agency does not have information regarding the manufacture, control, and release tests for this product. Specifically, the Agency has no information regarding testing at the manufacturing stages and in the final drug product for adventitious agents, including porcine or rodent viruses. Additionally, there is concern regarding the potential presence of other contaminants and/or allergens within the oral mixture that patients are being directed to consume.

In Thailand, meanwhile, helminth therapy is an approved treatment and is the home base for Goj’s company Tanawisa, where I obtained my TSO. Other worms are sold by a variety of providers with names like Biome Restoration, and Autoimmune Therapies, both of which operate out of the U.K.

A bottle of Trichuris suis ova containing 1,000 pig whipworm eggs. Eggs are contained in a salty liquid, which the author ingested every two weeks.

Visual: Leah Shaffer

Like me, many people end up discovering worm therapy through social media. I had previously written a brief story about worm therapy for Discover Magazine, but only began to take it seriously when my symptoms flared up and wouldn’t respond to the usual anti-inflammatories. When your guts are bleeding and you feel sick all the time, any inhibitions about alternative therapies melt away. But I never felt like I was embracing pseudoscience. Although clinical trials have been a bust, no published data suggested there would be any dangerous side effects associated with TSO therapy. And, through social media, I found a welcoming group of cohorts with even more encouraging stories to share.

A Facebook group called Helminthic Therapy Support — formed four and a half years ago — serves as the go-to spot for all things related to helminth questions. The main administrator is John Scott, an Englishman who says he participated in early safety trials for hookworms in treating Crohn’s disease. He describes regularly dosing himself with hookworms to keep his Crohn’s disease, food and environmental allergies in check, and he has become a true believer. Before discovering hookworms, Scott says, he had difficulty eating a wide variety of foods.

On the Facebook page, Scott runs a tight ship, keeping the discussion civil, mostly scientific, and free of anyone trying to directly peddle worms to the group. Curious newcomers are often pointed to the latest scientific research, and to helpful documents that offer tips on the care and keeping of worms. Most participants assiduously avoid offering medical advice — but the group does provide a list of established companies that offer helminths, along with details about the products and pricing.

Group members are even cautioned not to take photos of their worm packages, to avoid providing any helpful information to customs control agents who might be lurking on the page. “This could have devastating consequences on those who need access to worms,” says Scott, “so this is why we keep a lid on everything.”

Aside from the social media groups, helminth therapy does have an advocacy group called the BioTherapeutics, Education & Research (BTER) Foundation, which supports research and education on treatments such as helminth therapy or the use of maggots to treat wounds. The group does not actively lobby entities like the FDA to allow helminth imports, according to its director, Ronald Sherman. The main challenge in bringing forth these treatments is the prohibitive costs of clinical trials, and, that researchers haven’t settled on one single helminth or type of therapy to test, he adds.

For his part, Weinstock says he has mixed feelings about seeing people self-treating with helminths. There’s risk in having people source these worms over the internet, obviously, since they may not be able to check the safety of the organism. Worms like the hookworm and whipworm have to be grown inside a human and eggs must be harvested from their feces, which means there’s potential risk of transfer of pathogens — though no one in the DIY worm network has reported any such problems from listed worm providers. “I’m not opposed to using an alternative approach that’s less well studied,” Weinstock says, “as long as we can watch that patient carefully.”

New York University microbiologist P’ng Loke also warns that too little is known about the precise mechanics of helminth-gut interactions to make blanket declarations about any single species and the benefits they might confer.

Loke’s recent research, for example, suggests that helminths might not work alone in modulating immune response, but rather in partnership with other microbes in the intestinal mucous. In that study, Loke and his team used whipworm eggs to treat mice bred with a gene mutation associated with IBD. The treated mice saw a ten-fold increase in a group of anti-inflammatory bacteria called Clostridia, and a thousand-fold decrease in the number of Bacteriodes — a group of bacteria associated with inflammation. It’s likely the Bacteriodes were being out-competed by the Clostridia, but the implication was unmistakable: Not only do helminths secrete proteins that can reduce inflammation, they also seem to be associated with the growth of other gut microbes.

While Loke has seen positive outcomes from helminth therapy, he notes that it is also possible for a helminth infection to exacerbate colitis symptoms by elevating a type of inflammatory response in the colon lining. “If helminthic therapy becomes widely used,” Loke and his colleagues noted in one study, “it will be particularly important to separate patients into groups that may respond, may not respond, or may suffer disease exacerbation from infection.”

But Goj has grown impatient with these sorts of clinical formalities, and he has set his sights instead on getting TSO approved in Europe’s “novel food” category — and eventually doing the same in the United States. This would have TSO regulated as a sort of dietary supplement, rather than a medical treatment, and Goj is hoping to set up a production facility set up in North Carolina.

If TSO is approved for such use, he says, he’ll be able to lower the price, and will likely find eager buyers. According to Goj, his application for TSO to be novel food is currently being reviewed by staff at the British Food Standards Agency and he is still in process of completing his application to the FDA. Representatives from BFS confirmed it is still under review.

It is unknown whether other worm products have gone through a similar process at the FDA, because the agency does not disclose that information.

In the meantime, researchers like Alex Loukas, the Australian parasitologist, are still hoping to develop a pill that could mimic the benefits of helminths. Loukas first isolated beneficial worm molecules by culturing hookworms in the lab and collecting their saliva. Within that saliva, Loukas identified 200 different proteins — basically a buffet of potential anti-inflammatory molecules to sort through. His team has tested one of the proteins on mice and found it protects against the development of colitis and asthma. His work had attracted funding from the Philadelphia-based pharmaceutical company Janssen Biotech, and he is currently looking for new investors.

A micrograph of an egg from the “human whipworm,” Trichuris trichiura. It is among the primary species of helminth that patients are buying online for self-treatment. Will it ever make it to the pharmacy?

Visual: CDC

Of course, this begs the question of how — or whether — a pill mimicking the effects of a worm would work any better than drugs like TNF-alpha inhibitors, which are already on the market. For his part, Loukas describes worms as “stopping inflammation from occurring in the first place, rather than trying to mop it up after it has occurred.” Drugs like TNF-alpha inhibitors come in after inflammation has been triggered by immune signalers, he says, while the worms are adjusting the immune system upstream, before inflammation even begins to start.

Whether these and other discoveries will lead to new treatment options for the desperate masses seeking some measure of control over their bowels — and a variety of other disorders — is by no means a given. While there is something of an arms race right now for microbiota-derived therapies, some researchers suggest that, much like direct worm therapy itself, parasite-based medicine development remains something of a funding orphan.

William Harnett, an immunologist at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow who uncovered a worm molecule that holds some promise against allergies, asthma and lupus, says that while it is possible to obtain support for research into these molecules, obtaining funding to move towards the pre-clinical stage is more difficult.

He also says he didn’t start out to seeking a worm pill at all. Rather, his team was hoping to develop diagnostic tests for a group parasitic worms — filarial nematodes — that can cause elephantiasis and river blindness and other devastating disabilities in the developing world. Along the way, Harnett and his fellow researchers stumbled onto something beneficial in this group of otherwise harmful worms: Because they were trying to stop the host’s immune system from eliminating them, they were also stopping similar inflammatory responses that cause other diseases.

In subsequent tests with mice, the team has shown that the protein behind the nematode’s action, which Hartnett dubbed ES-62, can prevent the development of arthritis and other conditions.

Working with chemists at his university, Harnett has turned ES-62 into “drug-like small molecule analogues” — basically molecules that would be easy to manufacture and turn into a drug — that still retain the positive effects of the original protein. He knows there’s demand for such treatments because desperate patients have contacted him asking for help with their autoimmune disorders. Though Hartnett says the industry is cautious, he’s begun to receive queries from drug companies about testing his molecule.

Whether these initial stirrings will ever reach critical commercial mass for Hartnett or any other scientist remains to be seen, but helminth researchers have plenty of as-of-yet unexplored helminth proteins to occupy their time. Loukas, for example, notes that he’s found huge “families of proteins,” all of which may well have varying anti-inflammatory properties. “They’re each different enough from each other to suggest that they have subtly different functions,” Loukas says, adding that it may well be that a combination of multiple worm molecules will prove most effective in the treatment of IBD and other disorders of the digestive tract that seem to accompany modern life.

Or perhaps, he says, different molecules will service different shades of inflammatory disease.

“All of that,” Loukas says, “lies ahead.”

Leah Shaffer is a freelance science writer based in St. Louis. Her work has been published by Science, Discover, Wired and the St. Louis Post Dispatch, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Dr. John McDougall (“The McDougall Plan”) was dying of ulcerative colitis, while in medical school. He healed himself through a vegan diet. He’s still around going on 50 years later.

On YouTube you can view the videos of Dr. Joel Wallach who promotes a line of supplements he claims can cure most of these “autoimmune” conditions though he also argues for absolute elimination of gluten and oils.

As far as these arguments about what is “natural” and what we evolved in concert with–well we did not evolve with any refined grains, prepared “convenience” foods, GMOs, and especially NOT bags of Hot Cheetos the kids these days seem to virtually live on. As a lifelong allergy sufferer (both severe hay fever-going-on-asthma and skin-reactant “hives”) I would side with elimination (“rotation”) diet analysis before I would start infecting myself with worms. I took allergy shots in my teens and it made a dent in my symptoms but never completely relieved them. Only elimination of dairy and white flour did that.

Later in life I became afflicted with horrific dermatitis totally resistant to all medications. Only fasting stopped it, followed by total elimination of gluten prevented it’s return. Fasting has been a miracle cure for me. Dr. Valter Longo of USC in the g0-to guy on the medical research underlying this; he’s on YouTube too. You will NOT learn of him on corporate network TV for obvious reasons–you can imagine what the pharma and food companies think about this!

Everything you need to know about helmnith therapy and ‘helminth hackers’ can be found here: https://helminthictherapywiki.org/wiki/index.php/Helminthic_Therapy_Wiki

I have been using helminths for Hashimotos for nearly two years, and my partner for Crohns for over one year – both of us have had significant improvements in our health and I would recommend looking into to it if you have an auto immune disease. If it doesn’t work – a worm tablet can fix it.

Can these help scleroderma anyone know?

As a 68 year old practicing physician I have seen many things come and go, also have seen many things poo pooed initially as pseudo science become accepted as effective in certain applications (maggot treatment of wounds, probiotics, acupuncture, etc) It is well observed that children raised in modern clean environment have higher incidences of allergy and possibly autoimmune issues as adults. Having a dog or cat in the house, or playing in dirt as a child can transfer “training” to our immune systems. As I look back, growing up in a lower class home in a major metropolitan US city, I remember distinctly having been treated for “worms” on multiple occasions, as well as most of my classmates in grade school. IBD, gluten sensitivity and colitis were very rare diagnosis until the 1970’s. Anecdotally this makes one think about the relationship of childhood “infections” and later immunological issues. As stated in the article it is clear that 3rd world citizens have a much lower incidence of immunological diseases until they migrate to the first world. Logically, there must have been some mutually beneficial aspect of “parasites” and humans evolving together.

Is the organism still considered a parasite if undetected it is harmful but is beneficial to the same species in other instances (ex: used to treat specific disease)? Perhaps it’s a mutuacite?

Surely there would be other side effects from ingesting these worms? They’re living off what you eat so things like fatigue or malnutrition come to mind.

I was on course to have my sigmoid colon removed. I was having periods of severe debilitating painful inflammation that I was convinced was not due to diverticulitis alone.

I drove to Canada where I had shipped hookworms to a hotel, checked in, infected myself, and drove home. 17 hours straight driving.

I am now 5 months in and it is almost as if I have no problems with my gut at all.

As soon as the weather gets warm I think I will be traveling back to Canada to get another 25 or so to infect myself with.

Best 200 dollars I have ever spent.

The only reason it is illegal here in the states, I’m convinced, is to protect the profits of drug companies.

Hi Mike. Where did you order the worms from? (I’m in Canada). Thanks!

Mike can you tell me where you got the hookworms in Canada?

I wish the author discussed the level of desperation involved in ordering online from an unregulated supplier harvesting the eggs you ingest from feces.

I am in remission from ulcerative colitis because of human whipworms and hookworms. Pig worms are too expensive and evolved to live in pigs anyway. Also 3 months is way way too short to run an effective study. My colonoscopy went from “severe” to “minimal inflammation” in 15 months. I’ve stayed in remission the entire time since.

Ben