For All They Know: The Agonizing Uncertainties of Flint’s Water Safety

On the third day, I asked Gina Luster for a cup of tea.

“Oh, OK!” she said in her bright manner, sending her 8-year-old daughter, Kennedy, to the basement to bring up a case of bottled water. The Lusters opened a few bottles, dumped them into the tank of a cube-shaped device on the countertop, and then hit a button. We waited about 10 minutes or so as the white plastic machine performed its reverse-osmosis magic and gurgled “cleaner” water out of a lime-colored spigot. When there was enough, Luster put the water in a pan and turned on the range to boil it. While that took place, she twisted off the lid of another bottle to rinse out a mug, then stuffed those empties into a gigantic plastic bag, already awkwardly bulging and listing to one side with the mass of hundreds of other plastic bottles — two days’ worth, she said — on the landing of her basement steps. She then scrambled for a tea bag.

“It’s not just the lead. It’s not,” says Gina Luster, 42, who lives with her 8-year-old daughter, Kennedy, in Flint, Michigan. “It’s the E. coli and the Legionella, too. And God only knows what else. They don’t know.”

Ten months after a local pediatrician announced that blood tests among her patients were showing widespread, dangerous lead exposures in children across the city — and that she and other scientists suspected Flint’s water supply was to blame — my hostess believed this was the safest way to complete a simple task.

Who’s to tell her otherwise? Her process was laborious, obsessive. The reverse-osmosis machine, donated by a well-wisher from a Chinese company who saw her mentioned in a news report, may or may not be doing anything. The bottled water might not have needed further purification, although its label, adorned with images of Star Wars characters like BB-8 and C3PO — designed to promote the 2015 installment of the franchise — suggested it had been bottled as far back as a year ago.

Like so much else about life in Flint these days, there’s some disagreement about whether bottled water goes “bad,” but Luster takes no chances.

“How do you know what’s in the water from the sink?” she said, pointing at the place in most homes where most kitchen activity begins. Here, it has become little more than an inconvenient silver hole interrupting the countertop. “We can’t use that. I mean, we do sometimes, you know, with the filter. But we just had another boil-water advisory because of a water main break. So, it’s not just the lead. It’s not. It’s the E. coli and the Legionella, too. And God only knows what else. They don’t know.”

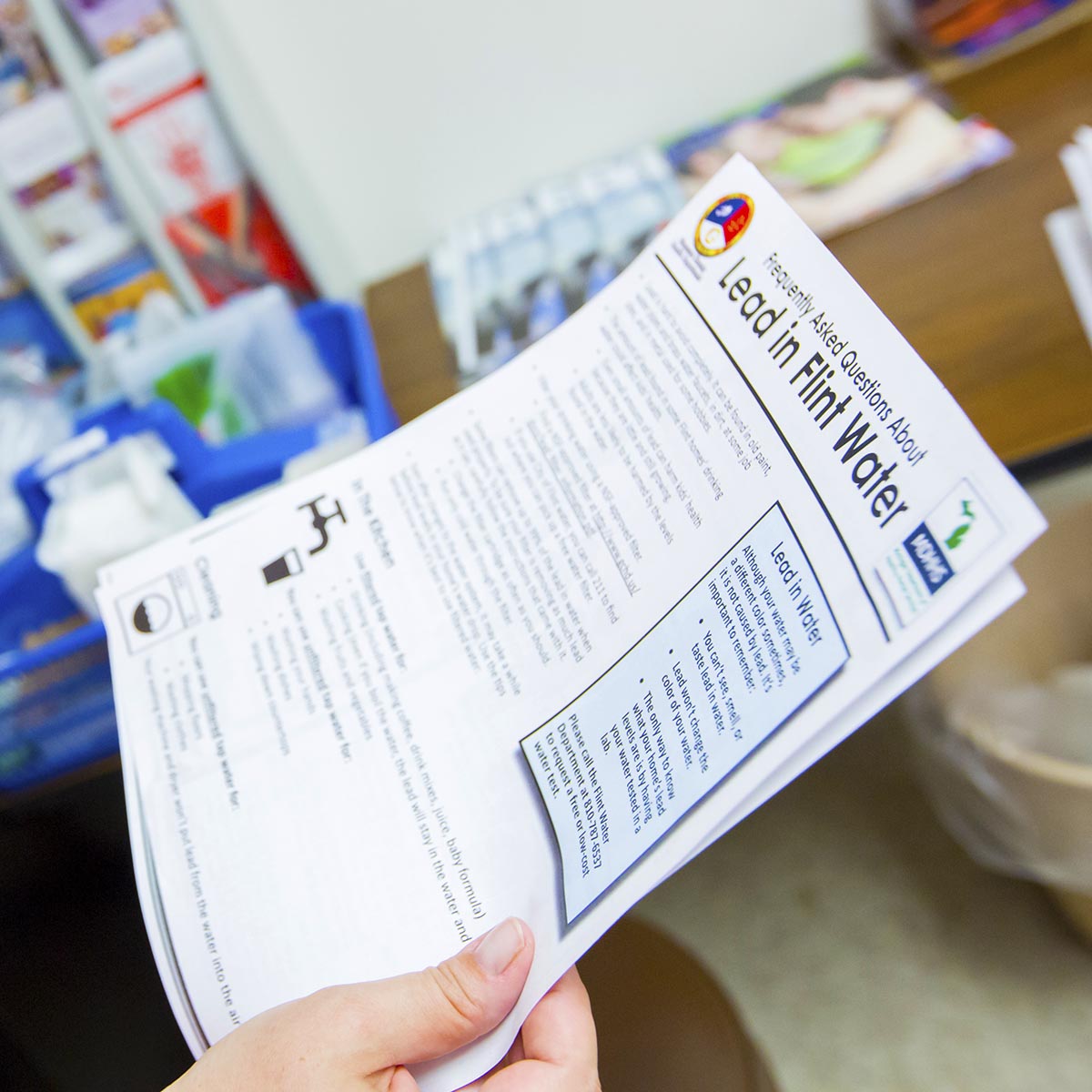

“They” often don’t. Professions of uncertainty on even basic scientific and technical questions have become something of an official refrain in Flint, and it’s one that residents like Luster and her daughter now hear, or infer, at almost every turn. What are the long-term implications of elevated blood lead levels? Should the water be used for showering? Does boiling help? What else might be coming out of the tap? Is it safe to drink now?

The answer to that last question, as of this month, is officially yes, so long as residents use a suitable filter. But it shouldn’t be surprising that not everyone believes this, in part because they’ve been lied to before, but also because on so many of these pressing questions, which still hang like a cloud over life in Flint, the most frequent and honest answer has all too often been, “We just don’t know.”

That crucial point was often overlooked amid the now-dimming klieg lights, which, for a time, bore down on this city. For however paranoid and suspicious Luster may seem, the infamous water crisis in Flint, Michigan — a mass poisoning rife with narratives of social injustice, banal bigotry, and regulatory ineptitude — belies a less frequently acknowledged truth: The millions of miles of pipes that deliver water to American homes remain, in many deeply troubling ways, a great mystery.

President Obama visited Flint last May — and made a show of drinking the water.

“We know very little about the microbial water quality in pipes and distribution systems and household plumbing,” said Joan Rose, a microbiologist at Michigan State University who has been actively researching the emerging Flint crisis since 2014. In March, Rose was awarded the prestigious Stockholm Water Prize for her research into water quality, microbiology, and public health.

“You mean we know very little about that in Flint?” I asked.

“No, I mean we don’t know that much about it at all, anywhere.”

“Well,” I replied, “that’s kind of terrifying.”

“It should be,” she said.

The vacuum of information extends well beyond microbes — and well beyond Flint. And while public health officials and scientists are careful to note that, on the whole, municipal drinking water in the U.S. is highly regulated, the roster of things we don’t really know — from chemicals and other contaminants that aren’t routinely tracked to the composition and even the location of any particular city’s pipes — is both substantial and a threat to the public trust.

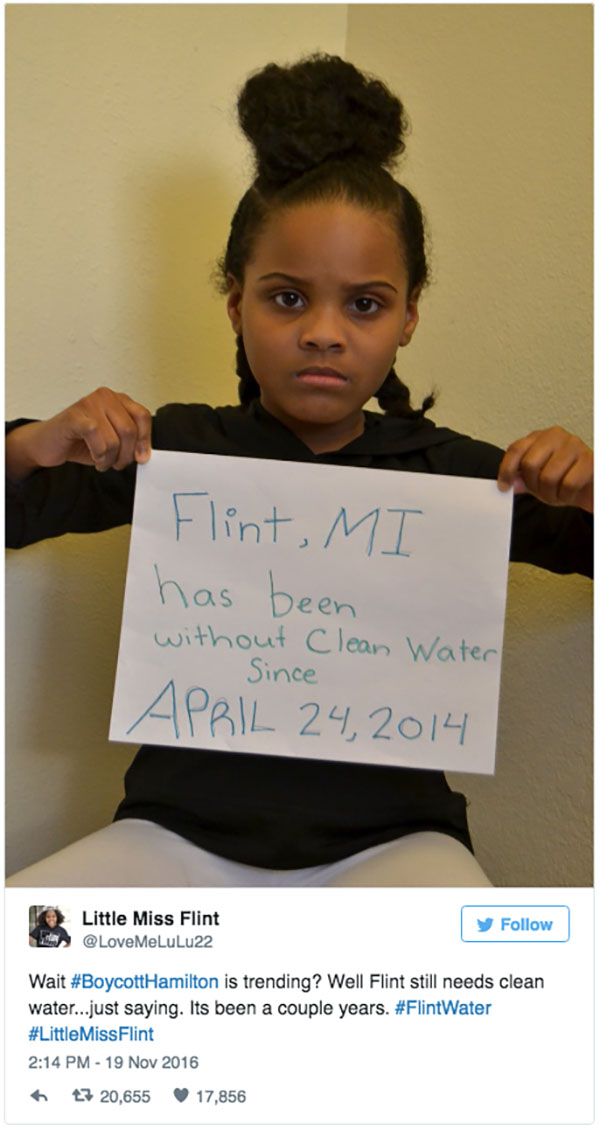

A recent tweet by Flint native Mari Copeny, aka “Little Miss Flint,” decrying the media’s disengagement with the city’s plight, has been shared over 20,000 times.

“When you lose safe water, you lose civilization,” said Virginia Tech civil engineering professor Marc Edwards, whose independent water testing at the behest of frustrated Flint residents forced the state to acknowledge the lead problem. “Once you see that, you see people paying the price, you’re ultimately forever changed by that. It’s not just people going out and buying bottled water. Civilization as we know it almost ends, for me. That’s what happened in Flint for 18 months.”

If your pipes are made of lead, Edwards added, “Using a National Science Foundation-certified filter provides a margin of safety that is strongly worth considering.”

Today, attention has shifted to other spectacles — to Donald Trump, to far-right politics, to battles over a North Dakota pipeline — though Flint residents resolutely take to social media to remind the world that they are still here, and still waiting for real answers.

Meanwhile, even as state officials announced this month that they planned to fight a court order to deliver water to residents who don’t have a verified water filter — an order they called “burdensome” — other government representatives have taken to talking openly about how little tap water they now use and why. “I’ve probably got more information than most people do and my kid will never drink the water from the faucet,” State Senate Minority Leader Jim Ananich, who represents Flint, told me during a recent visit. “I don’t think I’ll ever trust it. I was lied to for so long. And I’m in the very government that was lying to the people. I didn’t lie to anyone, of course, but I just don’t trust the government. It seems irrational, I know it intellectually, but I just…”

His voice trailed off as he looked at his infant son burbling in a stroller next to our table at a local café.

This sort of sobering contemplation is now easy to find in Flint, a largely poor, mostly black city in disrepair, where the residents now face lifelong consequences of being ignored and disempowered. But while the particulars of the Flint water disaster have allowed the world to behold its fate with a mix of outrage and “there but for the grace of God” distance, the large-scale lead poisoning was only the first shocking problem. It’s all the other contaminants that can affect poorly managed drinking water — and which Flint has proven to be particularly good at producing — that makes this a singular moment in the history of water science and regulation. Parallel to the lead exposure situation in Flint, after all, 12 people died and 79 others were diagnosed with Legionnaires’ disease — an especially virulent pneumonia caused by the Legionella bacteria, in 2014 and 2015.

Back at the Luster house, Kennedy pulled out a large piece of construction paper and a box of crayons to do some doodling — usually something with trees and girls with dark, curly hair — at the table where I sipped a cup of tea that I hadn’t actually wanted. In truth, after having slept on the Lusters’ couch for a few days and going through the motions of their lives with them, I had yet to see anyone do much of anything in the kitchen, so I was curious how they’d react.

The regimen they’d adopted reveals as much about the tyranny of uncertainty and suspicion — all of it entirely justified — that now governs life in this city. And until scientists and regulators can re-establish some modicum of faith among the people of Flint — a tall order, given how little empirical work has been done on the many ways our water treatment and delivery systems can catastrophically fail — uncertainty and suspicion are entirely rational positions to take.

“Everybody’s got this PTSD about water,” Luster told me. “I know women that you can tell they haven’t showered in who knows how long. Up under their nail beds, it’s just black. They’re not washing their hands, they’re not showering.”

How long has this been going on? The official timeline is well documented, but the truth is, even on this question, no one really knows.

Kennedy responded with a crinkled nose: “That’s kinda gross.”

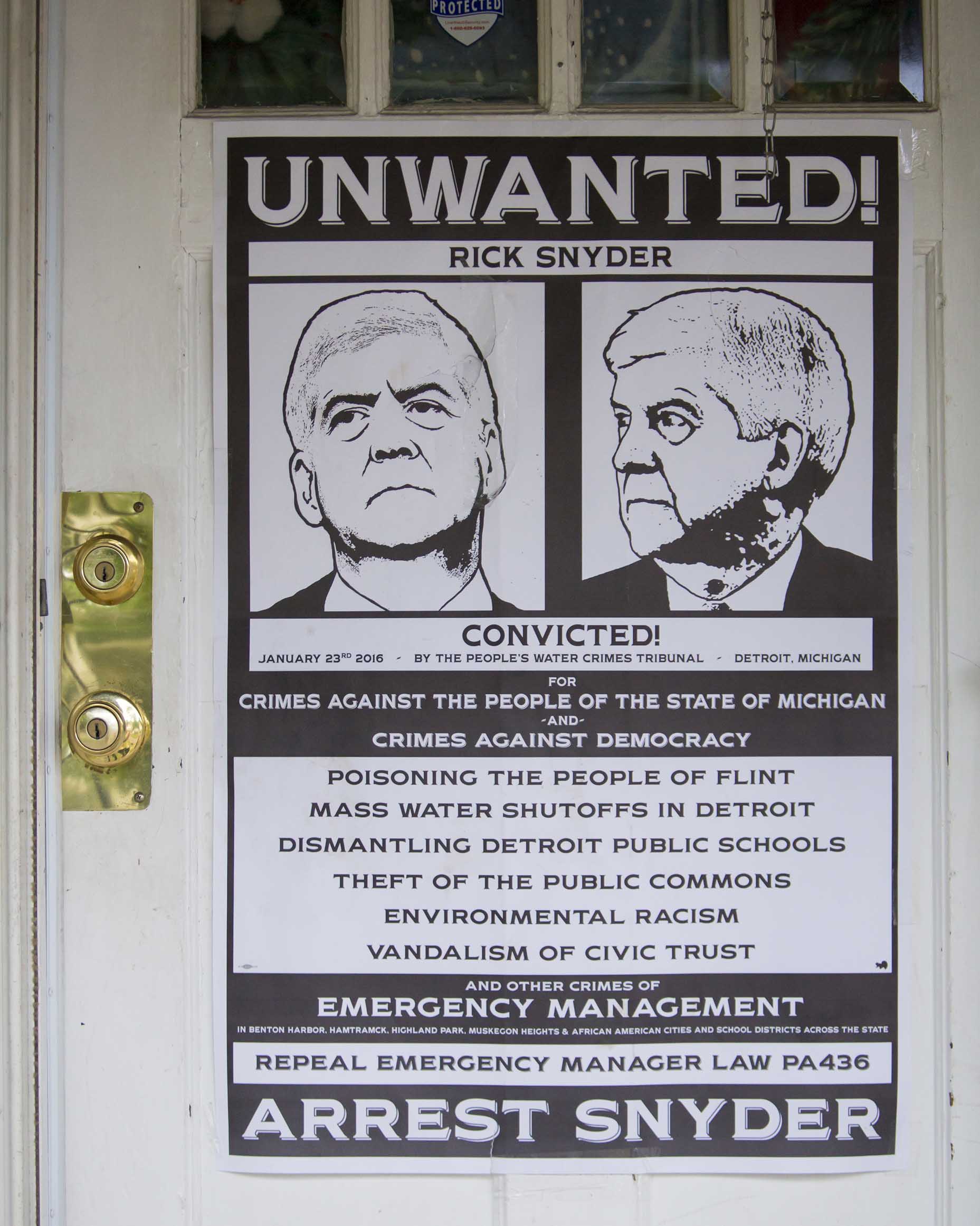

While pitched battles continue over where blame and legal liability lie, the basic facts of the Flint water disaster are not in dispute. The city was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy when Gov. Rick Snyder, as enabled by state law, put Flint under the rule of an emergency manager — a position endowed with more decision-making power than Flint’s own city council.

In April 2014, the city halted the supply of municipal water that had traditionally been piped up — at great expense — from a treatment plant in Detroit, about 70 miles away. In its place, Flint began taking in and treating water directly from the local Flint River. It was intended as a temporary measure — one that would save money until communities in mid-Michigan, including Flint, could complete work on their own $285 million water link to Lake Huron, the same source as Detroit. At the time, the target for completion of that project was mid-2016.

Shortly after the transition to the Flint River, however, residents began complaining about strange rashes and the color of the water coming from their taps. Initially, these complaints were dismissed, and residents were assured that the water was safe.

Later that summer, three advisories instructing residents to boil their water were issued after coliform bacteria was detected. The finding prompted operators of the Flint Water Plant — which had been inactive as a treatment facility for years while the city relied on pre-treated water piped up from Detroit — to boost the chlorine disinfectant levels. This might have been fine, says mechanical engineering professor Laura Sullivan at Kettering University in Flint, but the water facility opted not to also filter organic matter through activated charcoal, a common step at most water treatment operations.

“One can only imagine that it was to save money,” Sullivan said. “Anyone I spoke with, once they were aware that that was an issue — that there was no activated charcoal — was like, ‘You’ve gotta be kidding me? How in the world could they avoid that?’”

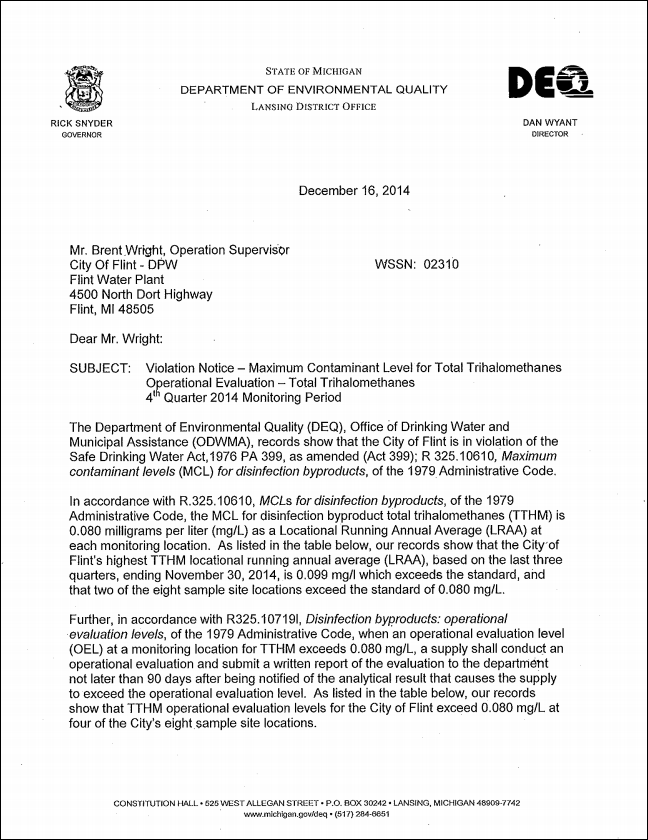

The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality found problems with the water throughout most of 2014. But the public was only informed of the findings in January 2015.

The problems associated with skipping that step are many. Organic matter in the water reacts with the chlorine to form trihalomethanes, or THMs, a known carcinogen linked to liver and kidney dysfunctions. The levels of total THMs are tested quarterly by the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, and measurements of 80 parts per billion or higher are considered actionable by the Environmental Protection Agency. Later it would be discovered that the DEQ’s tests had come back high throughout most of 2014, with six of eight testing sites in May and all eight in August of that year registering above the actionable level. But the public was only informed of the findings in January 2015, at which time then-Mayor Dayne Walling agreed to install six cells of activated charcoal to filter the water.

That was half the number of cells that a representative from Veolia, a Paris-based company that works with utilities, recommended to an advisory board — which included Sullivan as a member — but the THM levels did drop below the actionable threshold after that.

Still, local families began suspecting that other key water treatment steps, and other mounting problems, were being skipped or deliberately ignored by city regulators. Sullivan was suspicious, too. She had assumed the plant was following standard guidelines for treatment. “It was the fact that [the THM levels were] known and not shared with the residents that caused me to lose any faith in the assumption that people would be told if there was something unsafe,” she recalled.

The misgivings were not unfounded. Flint’s water, it was later revealed, was also not being enhanced with phosphates — chemicals traditionally added to raw water to coat the inside of lead pipes and prevent corrosion. This omission was especially hazardous because the river’s water, owing to high levels of chloride from washed-away road salt, is 19 times more corrosive than Lake Huron’s.

“Somewhere along the line, they lost sight of what they should’ve been doing,” said Jim Henry, environmental health supervisor for Genesee County, which includes Flint. “This shouldn’t have been a trial and error situation.”

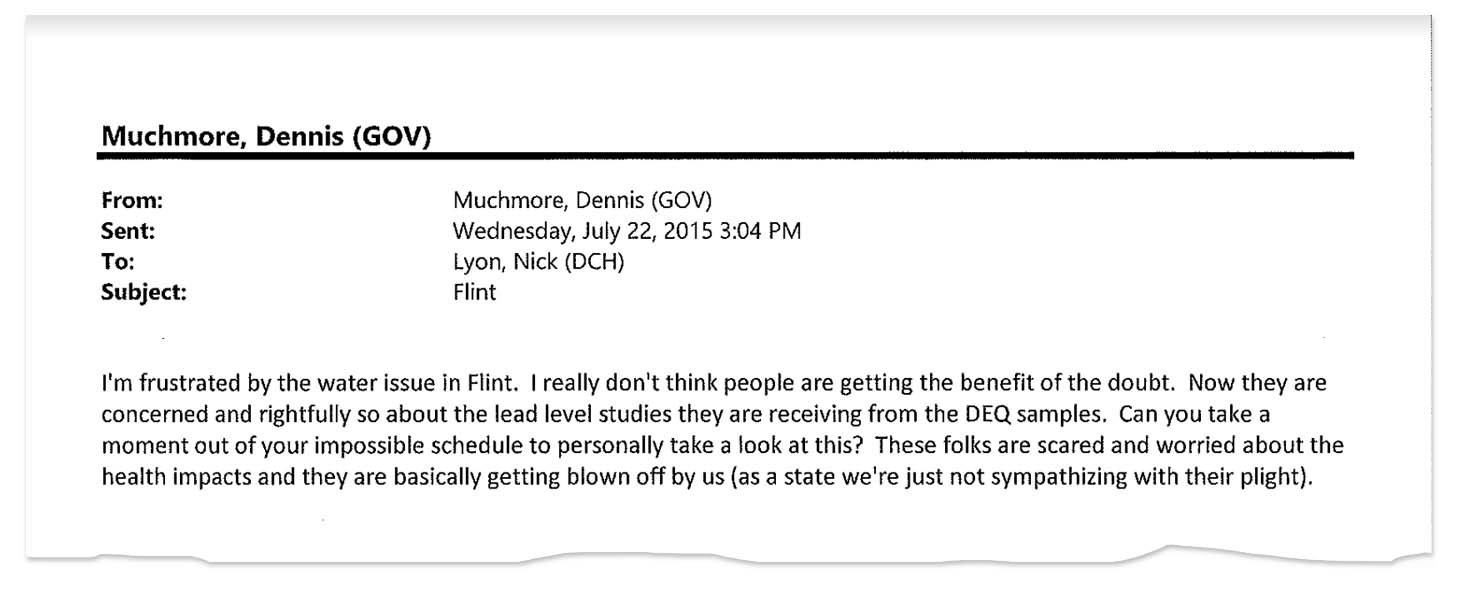

The result of the lack of corrosion controls was, among other things, a widespread leaching of lead — alongside discoloring flakes of rust — into the water. Even as children across the city were being diagnosed with elevated blood-lead levels, and despite early alarms sounded by some employees inside both city and state governments, officials at the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality insisted publicly that the water was safe. Privately, according to emails released in the wake of the controversy, officials were dismissive, sometimes callously, of the concerns of both residents and scientists. Even after a local pediatrician, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, showed in September 2015 that high blood-lead levels in children were epidemic across the city, the DEQ spokesman Brad Wurfel shrugged off the matter, calling it “near hysteria.”

In January 2016, the state declared an emergency and told Flint residents to only use bottled water or tap water filtered for lead. The National Guard was deployed to set up water giveaway stations, and celebrities like Cher donated hundreds of thousands of bottles to the cause. The state legislature approved millions of dollars for remediation, investigations were launched, and hearings were held in Washington and Lansing.

By early spring this year, Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette had filed charges and lawsuits against people and companies that, he alleges, either covered up the problems or failed to take obvious steps to prevent them.

But as stakeholders dug in for the long and arduous political and legal battles over where and how to assign blame over what happened, a new and arguably more daunting challenge loomed: What happens now with those hundreds of miles of pipe, and how will Flint residents ever again know for sure if their water is safe?

Gina Luster, like most Flint residents, paid little mind when the water switch occurred. She was a busy single mother, managing a Citi Trends clothing shop and raising an energetic daughter. She’d attended some school board meetings, but she hardly viewed herself as an activist.

On the Fourth of July in 2014, though, she was preparing to open the store when she collapsed. The last she remembered, she was reaching for the racks to stay upright. Then she was admitted to the hospital for a day, told by flummoxed doctors that she must have some virus and sent home with antibiotics. She never went back to work.

“I’d been feeling lethargic, I’d lost a lot of weight and I didn’t know why, thought it was stress,” she said as we ate Chinese take-out on her glass-top dining table one night. “I get out of the hospital and a month later, I’m still having severe body aches. I couldn’t move. I would rock back and forth. I was shaking.”

“Sometimes,” Kennedy interjected, “you would have to crawl up the stairs.”

“Yeah, my legs were like noodles, I couldn’t stand,” Luster said. “All this pain!”

“I went from being superwoman to I can’t walk,” she added.

At 42 and a scant 5-foot-4, Luster today is exhaustingly energetic. She has a narrow face and a bushel of long, thin braids, but it’s her eager, darting, chestnut eyes that are constantly probing the world for stimulation. She still suffers bouts of fatigue — afternoon naps are common and, I would discover later, she can be difficult to reach when she’s sapped — but otherwise it’s hard to imagine her in a debilitated state.

In mid-2014, though, she had dwindled from 180 pounds to 112. Specialists ruled out a thyroid disorder, multiple sclerosis, and lupus. She had mammograms, ultrasounds, and X-rays — with no answers. Around the time her hair started going brittle “like straw” and falling out, reports began circulating about brown water coming from taps around the city. That hadn’t happened at her home — yet — but she decided to ease off using the water because she figured it was hard. “As soon as I started backing off my water, I stopped needing my walking cane,” she said.

“The more I backed off,” she told me later, “the better I felt.”

Whether or not Luster’s laundry list of symptoms is attributable to Flint’s water is, of course, hard to pin down. Like so many other residents, she would eventually learn that her own blood lead levels were distressingly high, and that can come with a host of symptoms in adults, from fatigue and assorted pains to weakness and loss of appetite, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. In August, federal and state health investigators also suggested that fluctuations in pH, chlorine, and hardness in Flint’s water supply during the time it was being drawn from the Flint River could be linked to widespread reports — like Luster’s — of skin rashes. Physical stress from the crisis itself, along with changes in personal care routines and the onset of cold, dry weather, the investigators noted, could have made these and similar irritations worse.

But that same study also notes that reports of rashes and hair loss have continued long after the city abandoned the Flint River water and resumed its water intake from Lake Huron. “The city’s current water supply,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services noted in announcing the results of the months-long investigation, “does not contain metals and minerals at levels known to be associated with skin problems. In addition, nothing has been identified in the current water supply that could cause hair loss.”

Edwards, too, noted earlier this year that he had received reports of rashes from consumers using private wells, in addition to those on municipal systems, suggesting that these symptoms may be caused by other factors aside from the water.

Still, as the full scope of the water crisis became known and trust eroded in government regulators who had assured the public that the water was safe, it became easy, even rational, for residents to attribute each new itch and headache to the water coming out of their taps. And that reflex, as we now know, was not always wrong.

After all, over the course of 2014, Kennedy, too, was struggling. A bubbly child obsessed with Hello Kitty and the planets, she became quiet and testy. She complained of aches and her skin broke out in what looked like “a mixture between chicken pox and the measles,” her mother said. “She would be in the bed at night and she’d cry about her bones hurting,” Luster recalled. “We’d go to the playground and she’d say she couldn’t walk far, that her legs hurt.”

Luster now regrets not seeking medical help sooner, although she wondered at the time if Kennedy’s symptoms were just that of a child mimicking her mother. When she did take her daughter to the doctor, blood tests came back with an alarming discovery: Kennedy’s Vitamin D levels had fallen to virtually nothing. That, they would later learn, is a telltale sign of lead exposure. She was prescribed adult-dose Benadryl for the rashes and a monthly dose of Vitamin D, and Luster was left to figure out the rest. By trial and error, she came up with a mélange of shea butter, coconut oil, Vitamin E oil, hydrocortisone cream, cocoa butter, and lavender oil that seemed to help keep Kennedy’s itching at bay.

When Luster did take her daughter to the doctor, blood tests came back with an alarming discovery: Kennedy’s Vitamin D levels had fallen to virtually nothing. That, they would later learn, is a telltale sign of lead exposure.

Amid all this, the financial pressures for the Lusters mounted. The duo lives in a cozy two-bedroom, two-story townhouse with a living room and kitchen strewn with Kennedy’s school projects, laundry, toys, binders of documents, and stacks of unopened mail. There are also countless bottles of water of various sizes and shapes, empty and full.

Luster pays $650 a month for her unit in the back of a mammoth complex that is home to hundreds of low-income families — though she says she hadn’t always struggled. Her family’s fortunes, in fact, tracked neatly with those of Flint itself, starting in the 1950s when her grandfather drove up from rural Arkansas, walked into the General Motors plant, and asked for a job. He started that Monday.

Soon, he owned a home a block away from the GM property and saved enough to open a gas station. A few small grocery stores and rental properties followed, and by the time Luster was born in the 1970s, her family was part of a prosperous city’s African-American intelligentsia. Her grandparents bought her parents a home next door, and her grandmother hosted Algonquin-style daily breakfasts where everyone from auto executives to politicians to friendly neighbors would gather.

“If you looked at pictures of life then, you woulda thought we didn’t have any problems, any unemployment,” she told me as we stood across from the empty lot where the houses once stood off a road appropriately called Industrial. “All the neighborhoods were nice. Even what we considered the poor neighborhoods. Everyone was working. Even with only one parent working, people were able to afford a nice home.”

The city’s fortunes fell as GM and other automakers abandoned their factories in the 1980s and 1990s for less expensive operations elsewhere. Luster got a whiff of that early on when GM bought out the houses in their neighborhood because, it turned out, they’d been contaminated by factory-related chemicals. “We went from owning our own home, to renting our home, to my parents divorcing,” she said. “We never owned anything again.”

In her 20s, Luster had moved to Detroit, and then later to Houston, but by 2007, she was pregnant with Kennedy and back in Flint. Kennedy, whose father is vaguely in the picture and travels back and forth between Flint and Houston, was born in 2008. Luster found work in retail sales, but she was baffled at what had happened to her once-proud hometown. She hesitated to sign the lease on the townhouse they moved into in 2013, telling her grandmother she didn’t want to live in “the hood,” by which she meant the poorer, blacker section of the city. “Oh, dear, you’ve been gone too long,” Luster recalls her grandmother telling her. “This entire city is the hood. There’s really no way to avoid the hood.”

Luster didn’t get involved in activism surrounding the Flint water crisis until January 2015, when she started feeling better physically. By the time I first met her and proposed the idea of living with her for a spell, she had become a regular at city council events, protests, and community meetings. She and a handful of other so-called “water warriors” are in demand, so she’s been to Washington, Pittsburgh, Lansing, and Kalamazoo to talk about the crisis.

During the week I spent with her, we attended at least a half-dozen different meetings, most of them mind-numbingly dull, and she spoke up at every one. Where’s the donated money going? she asked. What’s going on with changing the pipes? What’s being done for the children? And their parents?

She’s rarely satisfied — and for good reason.

“A lot of this stuff that we’re finding out as far as information, we don’t know,” Luster said. “Even the doctors, you’ll hear ‘I don’t know.’ ‘We don’t know.’ ‘It’s a possibility.’

“You get sick and tired of hearing that.”

In October, just before the recent election, Luster shared her thoughts on what was motivating her to go to the polls.

A concern for scientists like Michigan State’s Joan Rose and Virginia Tech’s Marc Edwards is that the lead exposures in Flint — while serious — will overshadow the broader discoveries and alarms raised by what happened in the city. A decade ago, Edwards was among the first scientists to suggest that municipal water systems could be exposing consumers to what he dubbed “opportunistic pathogens.” In the case of Legionella, for instance, the commonly held wisdom was that it bred primarily in cooling towers and spas, places where there’s standing water that gets aerosolized and then breathed in — often by vulnerable populations like the immune-compromised in hospitals.

Edwards theorized — and then proved in lab experiments — that something else could be at play. The water treatment industry had spent a century focused, successfully, on preventing fecal and waterborne pathogens like cholera from killing its customers while, he said, ignoring the prospect that microbial bacteria could also be living in our pipes and water tanks. He began arguing that this was “the next great public health frontier for the water industry,” and by 2008 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began tracking data about Legionella cases contracted through municipal water.

“We realized that more people were dying from Legionnaires’ disease from tap-water exposure than from all of the fecal pathogens that we’ve been fighting combined,” Edwards told me. “It was always there, of course, but we just didn’t know about it.”

The water treatment industry had spent a century focused on preventing fecal and waterborne pathogens like cholera from killing its customers, said Virginia Tech environmental engineering professor Marc Edwards. But microbial bacteria could also be living in our pipes and water tanks.

There are roughly 50,000 community water systems in the United States, according to the EPA — which serve the majority of the population — and over the course of the 20th century, they have worked to create some of the safest drinking water in the world. The Safe Drinking Water Act, passed in 1974, is the main federal law under which the agency both sets drinking water quality standards, and oversees state and local compliance with them.

Still, many municipal water treatment and delivery systems are, like Flint’s, very old — and many decades after their installation, something of a mystery. The CDC itself estimates that millions of waterborne disease cases are likely to occur every year, though the precise impact is almost impossible to quantify. In part, this is because nobody is carefully tracking each incidence of most of the diseases that Edwards says can be delivered through our pipes — bugs like nontuberculous mycobacteria, which causes respiratory disease; a brain-eating bacteria called Naegleria fowleri; and pseudomonas aeruginosa, which attacks the skin and lungs. In many cases, people may become ill — or even die — with ambiguous symptoms that are never properly diagnosed.

A 2012 CDC-led study examined health care claims and hospital discharge databases in an attempt to quantify the public health and economic impacts for water-related illnesses. It found that five primarily waterborne diseases — giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, Legionnaires’ disease, otitis externa, and nontuberculous mycobacterial infection — were responsible for over 40,000 hospitalizations and nearly $1 billion in costs each year. The study tallied an additional 50,000 hospitalizations for campylobacteriosis, salmonellosis, shigellosis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and toxoplasmosis, at a cost of another $860 million annually — “a portion of which,” the researchers concluded, “can be assumed to be due to waterborne transmission.”

In early July, I was set to meet Sullivan, the Kettering University expert, but she canceled because she was hospitalized with Shigella, a highly contagious diarrhea-causing bacteria typically found passed in unsanitary daycare centers and public restrooms.

Sullivan had been nowhere near any of these when she became ill, but she did notice a city water truck on her block and theorized that maybe a drop in water pressure gave the bacteria the chance to get into her supply. “They are not considering that it was in the water supply,” she told me weeks later in the student union cafeteria where she just watched me eat because she still felt nauseated. “I don’t know what kind of evidence would be necessary for them to do that.”

In fact, neither Edwards nor the CDC would rule it out. By October of this year, Genesee County, which contains Flint, reported 85 cases of Shigellosis, and neighboring Saginaw County reported 49. As usual, answers were hard to come by. “There have been no definitive answers to what is causing this outbreak,” said Dr. Pamela Pugh, Flint’s newly appointed chief public health adviser, at a mid-October press conference to announce a CDC-aided epidemiological investigation is underway. “We know Flint is a unique situation. We’re not going to allow this to be addressed by a casebook or what we see typically as the causes of these illnesses.”

Translation: Who knows?

When Edwards first heard about the THM levels in Flint and saw the images of brown water on the news, he traveled to the city to see if, as he suspected, there was a corresponding Legionella outbreak going on. The lack of corrosion controls, he’d correctly theorized, had given Legionella bacteria a steady diet of iron and the lack of disinfection it needed to feed and grow. Add in the fact that the Flint River’s water was a few degrees warmer than what had come from Lake Huron, and conditions were ideal for a bacterial invasion.

“Now, in Flint, we have the worst living laboratory imaginable where you can study just how bad Legionnaires’ disease can get if the water system is not run effectively,” Edwards said. “The answer is: Wow. Very, very bad. Twelve people died and every indication is that it’s from the water system.”

There is a companion theory to why Legionella in particular hit the water supply with such force. Henry, the county environmental health supervisor, notes that the lack of corrosion control had been leading to a large spike in water main breaks, providing openings for bacteria to seep into the system. Edwards offers doubts about this theory, but Henry has run into a huge challenge in testing the idea anyway: City Hall. He has asked repeatedly to be notified when water mains break so he and his team can track them in the event of an outbreak, but that hasn’t happened consistently. What’s more, Henry says he has requested information on all water main breaks in 2015 — the one full year when the lead and Legionella crises collided — but “they haven’t been very cooperative even to this date,” he said, noting in a follow up email, however, that he’s now finally making some progress.

When I asked who had been standing in the way, specifically, Henry did not hesitate: “The mayor’s office.”

Having been raised in Flint himself, Henry finds it difficult not to take the lack of concern personally. “You see the mayor or the governor come down and do whatever they do, but it’s for show,” he said when we met at his office in July. “They’re not doing anything. They don’t walk down these roads. They don’t see people. They don’t knock on doors. They don’t talk to people.”

“People come in my office crying with their kids — they’re lead poisoned,” he continued. “I’ve talked to people that have Legionnaires’ disease and their kidneys are failing. Still. And it all could have been prevented if these people would have done their job right the first time.”

On the Safe Drinking Water Act, Henry’s thoughts were unequivocal: “That thing’s garbage.”

Pugh, at the press conference in October, promised better cooperation, but Edwards is unsurprised by the complaints. “I have to say, the level of dysfunction is kind of historic. The levels of distrust are definitely impeding the recovery and contributed to the disaster in the first place. I’ve never seen anything like it. And I’ve seen a lot.”

On a frigid early afternoon in March, the focus of the nation turned to the corner of Pierce Street and Greenfield Avenue, where the pavement outside Barry Richardson II’s house was an open trench. The first lead pipes were about to be removed and replaced with copper conduits under a new city pilot program, and CNN, MSNBC, and local TV affiliates across Michigan cable went live. This has been the focus of a great deal of the political effort to “fix” Flint — the notion that the best way to make the water safe again is to rid the city of any pipes made of lead or galvanized steel.

Richardson, in his late 20s with a daughter and a then-pregnant fiancée, said he was simply elated that he would soon be able to shower in his home again without concerns. Mayor Karen Weaver stood with him and announced to the world, “It is a great day for the city of Flint and it is a day that we have been waiting for. The goal is to get the lead out of Flint. We need to be focused a complete renewal of our city’s water system.”

Last March, city officials joined work crews on site to inaugurate Flint’s massive pipe replacement program.

At a cost of about $500,000, the program replaced 33 lead lines that went from homes like Richardson’s to the curb. A $2 million second phase that replaced another 218 lead lines wrapped up in October, and another $25 million is available for a third phase, which intends to cover the replacement for another 788 homes in the city.

The problem is, Flint has about 50,000 residences. Of those, officials know for certain that about 5,000 have lead lines, and another 11,000 are known to have galvanized steel conduits which, owing to all the corrosion that has occurred, are equally troublesome, because experts say they now harbor lead residue in the nooks and crannies of their rough surfaces.

About 25,000 lines are known to be made of copper, and won’t need replacing.

But that still leaves 10,000 lines, the composition of which is entirely unknown. “Right away you can see the problem,” said retired Brigadier General Michael McDaniel, dispatched by the governor’s office to oversee the pipe replacement operation. “We don’t know what we got.”

Flint — first incorporated amid the Saginaw lumber boom in 1855 — is an old and impoverished city with the sort of haphazard administrative and recordkeeping habits one might expect. So when McDaniel first endeavored to figure out where the lead pipes were, he discovered that much of the necessary archival material was kept on index cards. Many of these were illegible or damaged, many others simply nonexistent. He thought they’d struck gold when a retired city employee named Wilfred Alvord brought in a 32-year-old black ledger with plat-by-plat maps that indicated the type of piping at every building in tiny letters. Yet the book had sustained water damage while moldering inexplicably in his basement for years, and while other copies existed, many of these records, too, were indecipherable.

Scientists at the University of Michigan-Flint were able to translate as much of the information as possible into a map and extrapolate, for instance, what type of service lines were most likely, given the era during which the homes were built. But it’s neither precise nor certain to be accurate. To supplement the data, in fact, McDaniel floated the idea of asking residents to take a refrigerator magnet into their basements.

“We want them to scratch the pipe [that goes to the meter],” he said. “If it scratches, you can tell if it’s copper. If it’s not copper, you put a magnet on it. If the magnet sticks, it’s galvanized [steel.] If it doesn’t stick, it’s lead.” No such project was implemented, but McDaniel explained later that some funding for the second phase of service line replacement was used to ascertain the composition of pipes connecting to almost 200 residences.

When I met with McDaniel and his colleague, Captain Nick Anderson of the Michigan Army National Guard, in mid-July, they were excited to talk about an idea that has popped up to tackle the pipes that have proved to contain lead. The 3M corporation had reached out to tell them about a product they’ve used in Great Britain that relines the inside of corroded service pipes with a polymer resin, part of a line of products under the company’s Scotchkote brand. Rather than open trenches on every street, pulling out old pipe and installing new material, perhaps a faster, less disruptive and significantly less expensive solution would involve spraying the inside of the existing pipes with this material?

According to Fred Schiller, 3M’s business director for infrastructure, this solution could coat between 10 and 20 service lines in one day. “It basically provides a pipe inside a pipe,” he told me by phone.

The company is currently in conversation with Flint about the Scotchkote product, though it is not yet approved for use in drinking water pipes in the U.S.

On the City Hall conference table where McDaniel and Anderson explain the benefits of the Scotchkote solution is a prop — a cross-section of pipe with an inch-thick gray coating on the inside of it. The benefits are many, said Anderson, who estimated a 75 percent savings over service-line replacement, and a 30 percent savings for water main repairs. “We are advocating for considering this method and maybe as a partial pilot,” McDaniel added.

Yet there are many doubters. Sullivan, the Kettering scientist, said not replacing the pipes themselves is asking for a future disaster to sneak up on Flint. She explained that if you coat a metal to prevent it from corroding, “once there’s a pinhole disruption in that coating, the rate of corrosion at that pinhole is inversely proportional.” “If I have a surface and I coat it, and I have a pinhole in 1/1000th of that area,” she elaborated, “it’ll [corrode] 1,000 times faster,” at which point it would be too late.

Edwards said the 3M idea could be a feasible solution, but he doubts it would pass muster politically. “I think it works perfectly fine, by the way, but after you’ve betrayed an entire population, they don’t want to hear you’re going to fix it on the cheap. Especially when that’s what got them into this mess in the first place. So I think that’s almost off the table. Almost a non-starter. But who knows? There’s not going to be enough money to do everything people want to see, that’s for sure.”

That was Gina Luster’s instinctive reaction: “No one trusts any kind of solution that is not pulling pipes up,” she said. “We want them up and out and destroyed. That’s the only thing we can accept.”

Today, the already-treated water coming into Flint from Detroit is infused with additional phosphates and chlorine in an effort to help the local pipes regain their protective coatings and prevent further iron or lead from leaching into the system. These additional treatments began at the end of 2015 under orders from the EPA and CDC, and in early August of this year, Edwards’ team retested the water and found it dramatically improved. In an email, Edwards said the findings showed the water to be no more dangerous than any other water used for bathing, “although it still had excessive lead that could be avoided by using bottled water and/or filters.”

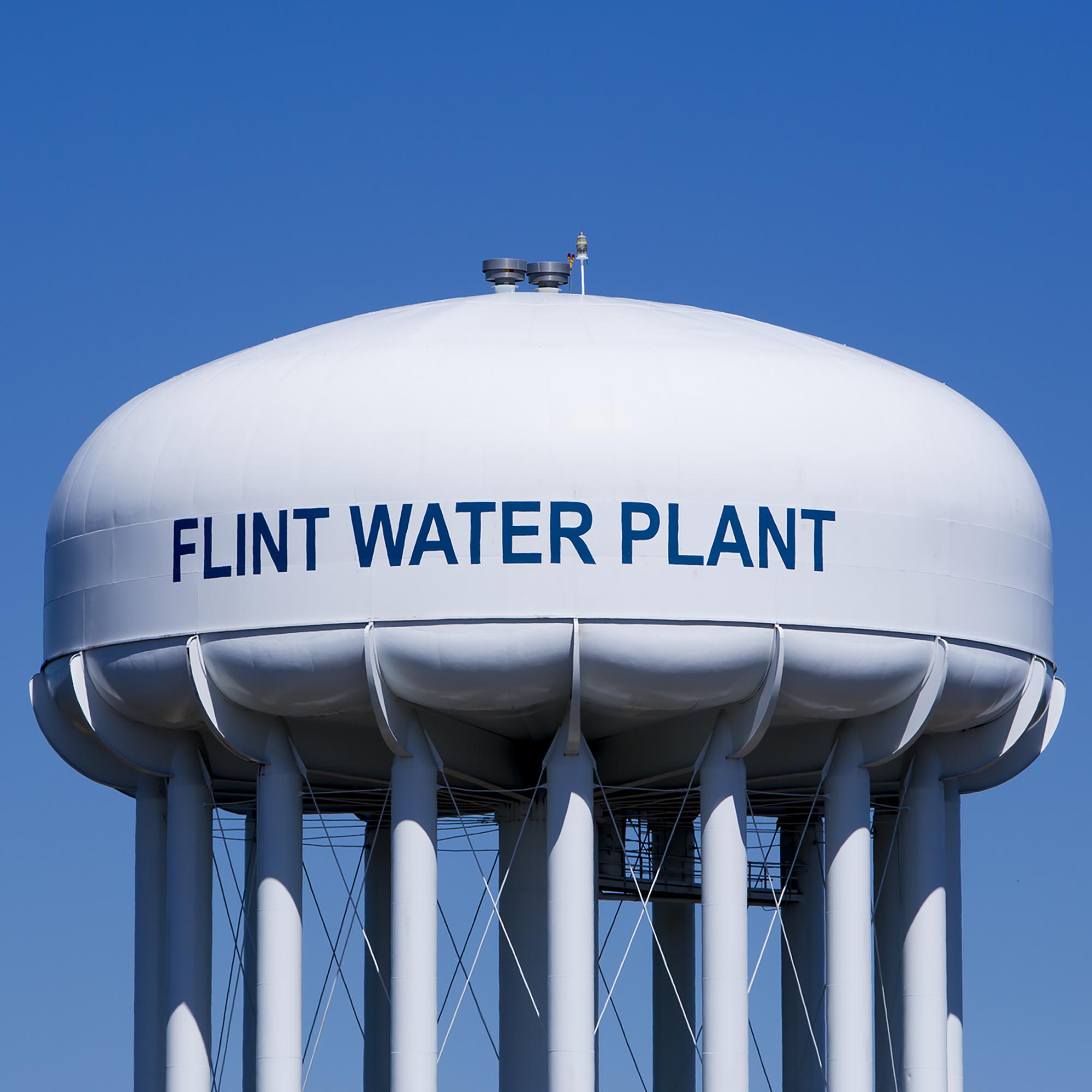

This has left the Flint Water Plant — a yawning campus on the bank of the Flint River that once churned with water treatment machinery — now mostly idle, and after months of pleading, I became the first reporter to have a comprehensive tour of the facility, which many now view as a crime scene.

I was met by JoLisa McDay, the plant’s new supervisor, and she was both relentlessly upbeat and reluctant to get drawn into the controversies that led to the community-wide lead exposure and, of course, her hire. She came from a managerial role at the Detroit water plant and she’s got a masters degree in chemistry, but she dodges even the most elementary questions about the past, such as whether anti-corrosives would have averted the entire crisis.

“That question I really can’t answer because truthfully in me coming here, I’ve been focused on moving us forward,” she replied in a Dolly Parton-esque cadence. “There’s been so many people, universities, engineering firms that studied and [are] continuing to study the past. If I keep looking at that, my team will never make it to doing what they need to do.”

The now-iconic water tower looms behind the main, low-slung brown structure of the plant, fronted by a semi-circle of brown stone pillars atop a few granite steps. In the lobby, which until October of last year rattled with the noise of pumps moving Flint River water, machinery stands museum-gallery silent.

The tour is equal parts generous and bafflingly opaque. McDay walks me all over the property and allows me to take photos from the outside of any of the buildings, even one of the tanks that adds chemicals to the water. But then there are other buildings and operations that are, somewhat incomprehensibly, off-limits.

We walk past a small red brick building that was once a pumping station when the water was being brought in from the Flint River. McDay had already made it clear the river will never again be used as a water source, so there’s no future purpose for whatever sits inside that building. “Can’t I just look in the window?” I ask. “No,” she said flatly. “That’s still my infrastructure. I don’t want to give you the keys to know where to access it.”

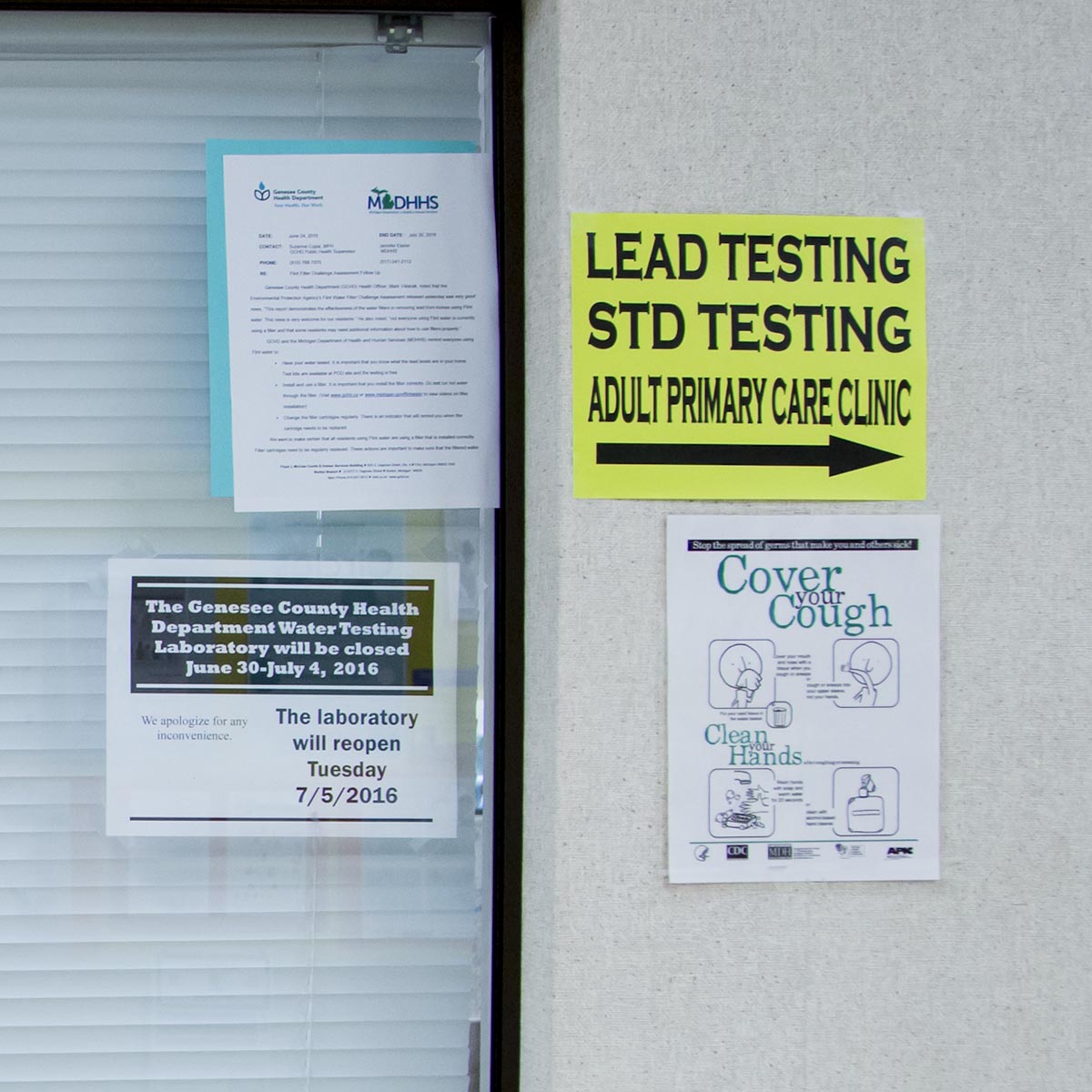

The reason offered is that the Flint Water Plant is a piece of critical infrastructure as designated by Homeland Security, but the vigilance is situational and inconsistent. For several months, members of the public were allowed to drop off water samples for testing here. Then, in May, a group of protesters that included my hostess, Gina Luster, staged a “die-in” where they lay down outside the front steps as the media watched until they got a call that the police were on their way and left. After that, McDay said, “I made the executive decision that we could no longer allow people on site for that purpose.”

The three previous times I’d been there, including one when I didn’t have an appointment, the gate was open and there was no officer in the little guardhouse. McDay explained that a garbage truck hit the gate two weeks earlier and it would no longer close. I didn’t bother to ask why it would take so long to fix at a site of such “critical infrastructure,” and in any case, McDay added that there’s generally nobody in the box anyway — though someone is watching on a video monitor via cameras, somewhere. “That you can’t see, like in any other facility,” she said. “Normally, we’d put you through a background check, make sure you’re not on any terrorist lists. I mean, how do I know you’re not going to try something?”

This didn’t happen for me, she said, because she presumed the mayor’s office vetted or vouched for me. (I gave no personal information necessary for assessing security clearance to anyone in Flint at any time in the course of reporting this story.)

The water tower at the Flint Water Plant looms over a designated water distribution site. State officials are now now fighting a court order to deliver bottled water to residents who cannot go to pick it up themselves.

We walked to what appears to be a three-car garage. Inside are three 220-gallon white plastic vats that are feeding chemicals into the adjacent building where the water is coming in from Detroit. “Because these are temporary systems, they’re something I can show you,” McDay said before she lets me shoot photos of it.

I didn’t protest, even though it seems like this is precisely the juncture where, for the foreseeable future, the system would be most vulnerable to evil-doers.

“What’s going on now is mandated by EPA order — the additional chlorine that you’re adding, the phosphoric acid, the ability to add sodium hydroxide,” McDay explained, referring respectively to disinfectant, corrosion control, and a chemical to moderate the pH of the water. “These are not installations you’ll see in any other system that’s using water from the city of Detroit. Only Flint is doing this. And it is a concern. The concern is that you’ve got one utility that uses Detroit water that has to do all of this, and if Flint is actually successful, you gotta wonder about the implications that it holds for everyone else that uses Detroit water. Will all of those other utilities have to put in these kinds of installations?” McDay asked aloud. “Or will Detroit have to actually put some kind of installation in their system in order to feed all of their customers because Flint has demonstrated that they can do it.”

Edwards would later find these remarks puzzling. Flint, at least in this sense, is different. “To use an analogy that’s especially bad and probably not applicable, ‘Once you have cancer, you have to do extraordinary things to get it stopped’… It really was necessary to add a lot more than what they were adding before to maintain corrosion control.” Noting that the extra phosphates are intended to hasten the rate at which the protective scale builds up on the inside of the pipes, he continued: “The rate at which the pipe is treated is directly proportional to how quickly it heals. It was added by Detroit as a maintenance measure, not a curing dose.”

“We’re barely under the action levels for lead now, maybe. Seven months with the curing dose puts it just now within the range of other cities,” he added.

Inside the main building, there is little activity to see except a series of pipes that are set up as a rig to transmit data on the water’s pH and other properties to EPA monitors elsewhere, and a laboratory where two scientists are doing other testing. I wanted to ask the lab workers about their jobs and whether, perhaps, anything might have been learned in these rooms that could have prevented the lead crisis from happening in the first place.

But McDay stridently stopped the employees from answering, insisting that I could not talk to them without their union’s approval. So, instead, I put the same question to her. “I can’t answer that question,” she said. “I’d have to know more about the process that was going on at the time. My aim is to move us forward. I know I’m not going to use the Flint River. I know there are certain chemicals I’m not going to use.”

“Looking backwards,” she said, “doesn’t advance the agenda going forward.”

That philosophy is a hard sell for people like Gina Luster, though not everyone is as hypervigilant as she is. Others in her complex are either letting their guard down with regard to the tap water out of sheer exhaustion, or because they think the whole thing is hype. It’s a hassle to keep going to the fire station to get bottled water or replacement cartridges for filters, after all.

One night, I wandered out to a courtyard where the neighborhood’s teenagers were milling, flirting with each other or, in many cases, just idling quietly by the glow of their smartphones. Only about half of the two dozen kids I chatted with said that the parents or grandparents who care for them are paying much attention to whether — or how — they use the water.

“My ma was real hyper about it for a few weeks, but how long do you not take a shower, you know?” said Dezzie Jackson, then a high school junior. His girlfriend, LaDonna, said her father’s been saying the whole thing is a big hoax. “I don’t know why he thinks someone would hoax about this, but that’s what he say,” she shrugged. Most households follow some sort of hybrid approach: Use bottled water whenever it’s around but, as another kid said, “Don’t go crazy about it.”

Luster said she’s done preaching, but she maintains a strict and cautious regimen — one still endorsed by experts in the city — and she and Kennedy follow it: Do not open your mouth in the shower, don’t stay in too long, and don’t let the water be too hot, because the heat ruins the water filters. Both mother and daughter alternate between using wet wipes to bathe and taking quick lukewarm showers or baths. When they need to wash their hair, the Lusters use the facilities at her mother’s house, located outside of Flint.

Though Edwards has said there’s no “scientifically valid to reason to believe that risks of bathing or showering in Flint are currently higher than in other U.S. cities,” Luster — who says the water from her home is still making her hair fall out — isn’t prepared to take any more chances. The reality is, the Lusters don’t “live in crisis” so much as they mold their lives around avoiding the crisis as much as possible. All of these months have created a sad, ridiculous, but seemingly permanent new normal.

The idled kitchen is among the biggest changes. “We live on takeout, canned pop, canned juices,” Luster said. “Before, I literally cooked every day…I’d make grilled chicken, put it on a salad. I’d make homemade fattoush all the time.”

“There was always salad along with two or three vegetables and rice,” she continued. “We used to drink right out of the tap. Every now and then I’d buy bottled water, but it wasn’t something for a regular basis. We were using tap water for everything. I was rinsing everything off. That summer after the switch, I was telling Kennedy to drink more water because we were starting to not feel well.”

“I’m saying drink more water, drink more water,” Luster recalled, “and the water was the problem.”

In early August, Kennedy went for a checkup and blood test. At the beginning of the year, her blood-lead levels were over 6 micrograms per deciliter. In April, it was measured at 5.3. This time, for the first time since she had been checked, it was under 5 — the line of demarcation for concern.

A week after my time spent living at the Luster residence, I was back in Flint for some more interviews, including a second visit with Jim Henry at the health department. I noticed the signs offering free lead sampling down the hall. The test was open to everyone — not just Flint residents — so I decided to have my blood checked on the State of Michigan’s dime.

The following Tuesday, the Genesee County Health Department sent me a link to a website with my results: I had been lead-exposed. In Flint. Most likely. The only thing the test really proved, of course, was an exposure within the prior month, and it’s possible that I was somehow exposed elsewhere. But there was little about my life in those prior weeks — other than my temporary residency with the Lusters — that would suggest any other risk points. I began thinking about the filtered tap water I used to brush my teeth, the unfiltered water that I had showered in, and everything I drank at local restaurants with signs that promised that their water was safe.

I’d taken the test on a lark — more as a way of having yet another now-common Flint experience than expecting any outcome worth writing about. Instead, more than two years after the city made the fateful switch to improperly treated water from the local river; ten months after this crisis exploded into the national consciousness; seven months after the governor held back tears as he took responsibility during his State of the State address; and two months after President Barack Obama gulped a glass of water on TV and inadvertently signaled that the worst of the crisis had passed, it appeared that I, too, had been poisoned by lead in Flint, Michigan.

The results provided little context other than a number and a scientific range. I did some Google searches, but otherwise I figured if there was any danger someone would probably be chasing me down. I was heading abroad on a different assignment and didn’t feel sick in anyway, so I didn’t even mention it to my family and quickly forgot all about it.

About a month later, during a phone call with Edwards, I mentioned my test in passing. He asked what my number was.

“Uh, 15, I think?”

“Holy shit,” he squealed into the phone. “Are you kidding me?”

“Yeah, I think so,” I told him. “Hang on. I’ll dig it up.”

“Fifteen is really bad,” he explained as I frantically hunted for the paper I’d printed out. “The level of concern for everyone is 5,” he said. “You’re three times the level of concern?”

“I found it,” I told him. “It’s 13.3.”

“Is that micrograms?” Edwards asked.

I read from the page: “U.I. — that’s micrograms?”

“Yeah,” he said. “Per deciliter? Per dl?”

“Per dl, yeah.”

Edwards gasped. “That’s not a good number.”

“What should I do? Should I be doing something?” I asked. “I’m a healthy 43-year-old. Does it matter?”

“Well, it certainly did not help you,” Edwards said. “Will it significantly impact your life? I don’t know. But there’s nothing you can do. There are people who will give you all kinds of chemicals to take, but the CDC doesn’t — health agencies don’t believe that helps.”

I took the news blankly, though my mind did drift to what other metals or microbes, besides the lead, might have sloughed through Flint’s pipes, passed through a tap, slipped through a spigot, or cascaded out of a shower head and, somehow, made it into my bloodstream. “OK, then,” I said.

“Yeah, I’m sorry, but the standard advice is that the harm, if any, is irreversible, and let’s make sure people do not get exposed,” Edwards offered. “Because once they do, we don’t know what to do about it.”

“It’s another thing,” he said, “that we just don’t know.”

Steve Friess is a former technology and politics senior writer for Politico whose freelance work appears regularly in Time, BuzzFeed News, New York Magazine, Al Jazeera America, and many more. He is based in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I always used to study piece of writing in news paapers but now as I am a user of

net so from now I am using net ffor articles or reviews, thanks to web.

[email protected] are a significant number of research papers in the sci lit that strongly indicate that skin absorption can be common, but that it loses its affinity for the red blood cells so does not register on the blood lead test, so for many years toxicologists just assumed that it did not pass through skin. this may be a big error. It would probably be prudent for ‘authorities’ that suggest peope could still use lead-elevated water to bathe in to review the literature before just assuming… as it could lead to even more law suites later. IMHO See: via Google: J.L. Stauber et al, ’94, Filon et al. ’06, Sun, C-C et al ’02, Florence, T.M. et al., Lilley, S.G. et al., Franken, A. et al, and associated citations on skin absorption of inorganic lead. Also, Si-Hao Lin et al. ’12. In other words ‘Look before you jump”. This problem is already bad enough… tragic! Showering in this water, may prove to be problematic as well as drinking it. IMHO

It is my understanding that lead is known to adversely affect calmodulin, which is very important in skin physiology. Could this play into the skin rashes??? especially if percutaneous absorption is happening in shower and bath use.Now, with schools all around the nation finding elevated lead levels…??? IMHO

We can do the science and technology to go to the moon and mars but we can’t seem to develop infrastructure that can transport water without undue influence from drinking water pipe leaching metals and other pollutants to harm public health. We can’t even eliminate fishing sinker use, that contaminates tackle boxes with a fine black nearly pure lead powder. This lead powder gets on hands, apples, sandwiches, cooler ice, and fish to be taken home to the whole family. Get a lead swab test kit from the hardware store and then check your old tackle box to get some idea of how you have spread lead contamination in the past.

As cities gradually started to avoid using lead pipes, they often started using galvanized steel pipes instead, the early galvanization processes were contaminated with cadmium as well as lead. These early galvanized pipes were far worse than galvanized pipes after much cleaner zinc became utilized in the process, easy zinc was contaminated. This apparently means that many additional pipes were leaching lead and cadmium during the acidification event period. Cadmium poisoning, even chronic low dose, has additional toxic effects potentials for the exposed populations. A sensation of aching bones can be a classic result of cadmium poisoning. Lead and cadmium are calcium utilization inhibitors, and can work synergistically to harm many physiologic pathways in the body that could produce symptom other than just the classic suite of lead toxic effect. these two toxicants combined, from the dissolving pipes, could easily damage the calmodulin in the body, that it instrumental in skin health as well as in deeper organs. This could be important to assess as potential for skin rash causation. AND, when the skin gets damaged, research shows that wash water containing lead can cause lead much better access through the skin into the body. The rashes are an important clue to additional harm brought by this devastating water pollution snafu in Flint.

Lead issues are being covered up by epa reg. ten staff in the nations largest lead Superfund site of Idaho.

I live in the original 21 sq. mile epicenter first designated as the 2nd larget NPL site in 1983.

I am a mother, grandmother, friend, neighbor and care about my children and the future of my community.

I am very involved with the grassroots work of the Silver Valley Community Resource Center a group that

has worked in good faith to bring vision, hope, lead health experts like Dr. John Rosen, Dr. Stephen Gilbert and

to the area to get help for our children. To this date, the only lead intervention program going on is SVCRC

Children Run Better Unleaded project, it is implementation of Medicaid law. Please contact them and

help get the word out about the documented cover up of epa about the lead health issues going on in my

community. Affected citizens face fear, repercussions for even saying the word LEAD.

EPA has $750,000,000 in settlment funds from the mining companies they are using to divide the

community and not help to develop the Comm. Lead Health Clinic/Center citizens have demanded and need.

thank you

These are such endless scenarios and demand a lot of attention. They have different perspectives and I agree with the points you have stated above. I also feel that if the basic necessities like food, water and shelter can be improved and taken care of in the future, we all will lead much better lives. This is really necessary for the ones who are under-privileged unfortunately.

More than 80% of daily lead intake, according to the World Health Organizations (googke WHO, lead in drinking water), comes from food and dirt (dust) in the air. The problems in Flint started when water was taken from the Flint River, while the river (like all rivers) is still polluted since EPA never implemented the CWA. These facts that most of the daily lead intake comes from food and air and that the Flint River is still polluted, were never mentioned by the media. If they had been, it certainly would have made a huge difference.