If you live in a major urban center like Chicago, the concept of wilderness might seem remote at best, hemmed in as you are by concrete buildings and asphalt streets. Thoreau wrote that “In nature is the preservation of the world,” but what nature would the city dweller expect to see except manicured parks with green lawns and non-native trees?

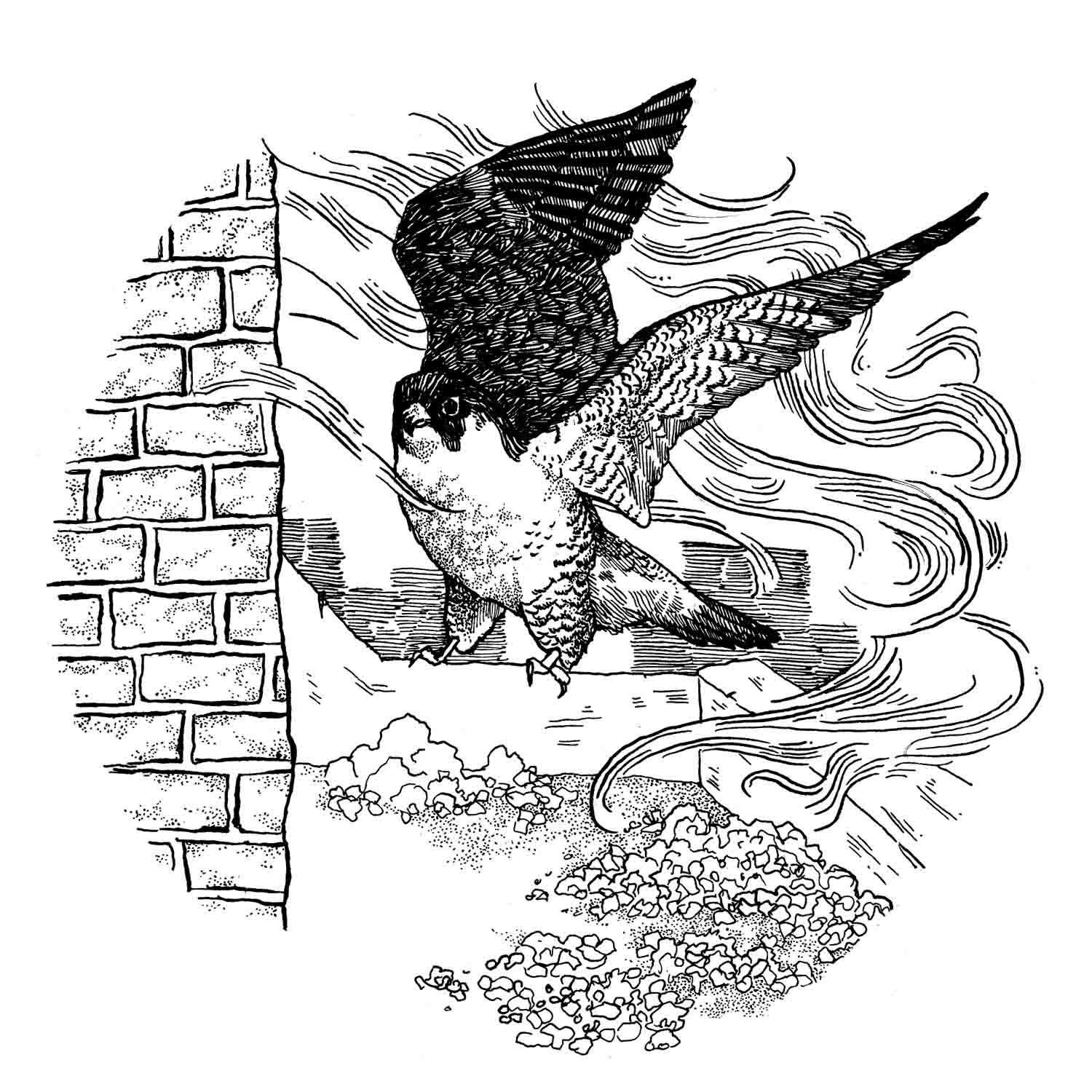

In “The Way of Coyote,” Gavin Van Horn, the director of cultures of conservation at the Chicago-based nonprofit Center for Humans and Nature, wanders the city by foot and kayak and discovers a surprising abundance of wildlife. He visits places like Northerly Island, which hosts several dozen acres of rolling prairie, and he spots animals everywhere, including a peregrine falcon perched on a library, a coyote on a golf course, and a beaver in the North Shore Channel. In fact, the city accommodates some species quite well: chimney swifts and cliff swallows readily adapt to urban structures, while coyotes, raccoons, and opossums can do fairly well if they don’t get caught.

For this installment of the Undark Five, I spoke with Van Horn about his encounters along the wilder byways of his hometown, our instinctive need for connection with nature, and his decision to invoke three figures as “spirit guides” for his book: the conservationist Aldo Leopold, the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, and the Native American trickster Coyote. Our email exchanges have been edited and condensed for space and clarity.

Undark: Urban wilderness seems like a fairly new concept. Is that correct? If so, what do you think has led to the growth in interest over the last several years?

Gavin Van Horn: There’s an environmental narrative — probably the most dominant one in the 20th century — that categorizes urban areas as degraded, decaying, and biotically depauperate. According to this story, to experience real nature one must escape the city. That narrative has some basis in reality. Particularly during the heyday of the Industrial Age, cities earned their smoke-belching, disease-ridden, malefic metaphors.

However, people have always sought out and actively created green spaces in cities. Most cities are built near areas where the conditions are favorable to life; a reliable source of water, for example. Urban renewal and beautification movements, including ideals for large urban parks as democratic spaces, are part of urban history, too. In some cases, urban planners were far-seeing enough to protect large areas of habitat or forest preserves that are now integrated within the fabric of cities.

So while the conjoining of the words urban and wilderness may be relatively new, the potential was there. With reference to cities, however, I prefer to speak of wildness (the self-renewing processes that create the conditions for the flourishing of life) rather than wilderness (typically large tracts of land or water that are formally designated for protection). The scale is different than it is in Denali National Park, for example, but wild experiences and encounters can be just as powerful and meaningful in urban areas.

In terms of increasing interest in urban wildlife, there is first a growing recognition that ecological communities don’t cease to exist where the city limit signs begin. Wildlife will adapt. Second, wildlife biologists are now conducting long-term studies about urban wildlife populations in cities around the world, providing insights into the lives we share. Third, an increasing interest in urban wildlife and nature is inspired by a deepening unease that people, especially children, are in danger of losing essential connections to the natural world.

UD: Urban wilderness is a bit of an oxymoron. How do you reconcile the two aspects, especially given that species (e.g., peregrine falcons) are now inhabiting urban-defined ecological niches (i.e., skyscrapers) that they would not have in the wild?

GVH: Habitat is habitat. We don’t need to reconcile the urban and the wild in this case; the peregrines have already done it. That’s a strong theme throughout the book: Other animals show us that they aren’t concerned with our concepts of what should be in a city. Is there food? Shelter? Enough room to raise one’s children in relative safety? If yes, then there are a lot of adaptable animals who can tolerate and benefit from human presence.

The next step is how to create cities that are more welcoming of other species, more generous in the way they are constructed, and more mindful of the ways in which other animals can thrive in our midst if the conditions are favorable.

Usually those conditions — large green spaces, connected trails, healthy waterways — are good for human well-being, as well. The Chicago River, for example, was once incredibly inhospitable to life — highly manipulated, channelized, treated primarily as an open sewer and a conveyer of industrial effluent. Over the last three or four decades, with better regulation, fewer industrial pressures, more extensive sewage treatment, and the restorative care of those who live near its waters, the river has become a wildlife magnet. I’ve paddled through the heart of Chicago alongside beavers, herons, turtles, wood ducks, dragonflies, and all sorts of other creatures — even had the pleasure of watching a mink chow down on a crayfish as I floated by.

UD: When you talk to Chicagoans about urban wilderness, what is their response? Are they open to sharing their city with wild creatures?

GVH: I think there’s a growing hunger for connecting appropriately, perhaps motivated by a vague sense of anomie. Of course, people have concerns: What’s that opossum doing in my backyard? There are squirrels in my attic! There are practical considerations, and sometimes tough decisions to be made — for example, about the impact of deer on native plant life. But the question you’re asking, I think, hinges on nurturing curiosity: How can people move beyond fear of the unknown or unfamiliar into acceptance and possibly even celebration of other forms of life?

To me, this is why urban areas are so important. We begin where we are; we cultivate our most intimate relationships and experiences close to home, where we live, work, and play. Most people will never have the opportunity to swim with dolphins in the Caribbean or hear the howls of wolves in Yellowstone. Our ethic of care, our empathy, our sense of how humans are dependent on other forms of life (pollinators, for example), our shared vulnerability in the face of change, and our capacity for wonder — all of these things are informed by daily practice and encounters facilitated by urban nature exploration. We can choose to enclose and insulate ourselves, or we can make micro-adjustments that gently place us in the pathways of other creatures.

UD: What are some of the benefits of urban wilderness? Why is it important to city dwellers?

GVH: The benefits are increasingly well-documented, from social health to personal stress reduction. Though it deals with a broader swath of immersive experiences than urban nature, “The Nature Fix” by Florence Williams is a book I would recommend for those interested in learning more about the neurological and physiological benefits of nature engagement.

The greatest benefit of exploring urban nature is the potential such places hold for fostering the recognition that humans aren’t a species apart; we live in the midst of a vital world — not atop it.

UD: Why did you choose Leopold, Lao Tzu, and Coyote as your “spirit guides”?

GVH: All of these characters profoundly influence how I perceive the city, and they share the quality of being boundary crossers. Leopold for his scientifically informed environmental ethics, and the way he integrated his field experiences and love of the land into a beautifully articulated vision of ecological wholeness. Lao Tzu (in the poetic clothing of the “Tao Te Ching”) for looking to the integrative, imminent wisdom of the natural world as a key to human humility. And Coyote, the adaptive trickster archetype of this continent, for his impudent, playful, confounding affront to so-called efficiency, utility, and presumed human dominance.

One of the most pleasurable chapters to write was the conclusion of the book, when I put the three of these characters together in conversation, roaming Chicago’s lakeshore after a pit stop at a bar. Each of them, in their own ways, provides reminders that humans are one species among numerous others in a more-than-human world — a world that invites our attention, fidelity, and care for its wild flourishing.

Sarah Boon is a Vancouver Island-based writer whose work has appeared in The Rumpus, Longreads, The Millions, Hakai Magazine, Literary Hub, Science, and Nature. She is currently writing a book about her field-research adventures in remote locations.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

In my yard in the southwest corner of Chicago, there are foxes, chipmunks, possums,garter and brown snakes, and living unpoisoned soil. The fireflies in the summer add to the magic. Rewilding nurtures the land and the soul.