From the work that made her famous — hard-hitting books of social criticism like “Nickel and Dimed” and “Bait and Switch” — you might not guess that Barbara Ehrenreich has a Ph.D. in cellular immunology. But the science of medicine plays a central role in her newest book.

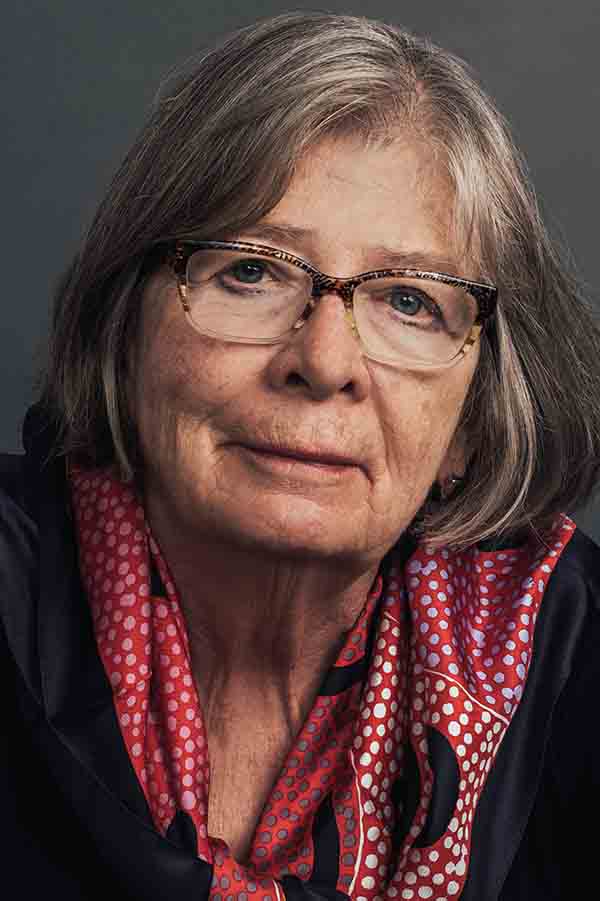

At 76, Barbara Ehrenreich forgoes cancer screenings and disdains “rituals” like the annual physical.

Visual: Stephen Voss

In “Natural Causes,” Ehrenreich takes aim at the American obsession with wellness at all costs. Now 76, she forgoes cancer screening, disdains “rituals” like annual physicals, and takes the culture to task for conferring special virtue on the healthy. The book’s subtitle does not mince words: “An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer.”

For this installment of the Undark Five, we spoke with Ehrenreich about the relationship between science and medicine, the effectiveness of mammograms, and whether the mind can really control the body, among other topics. Our conversation is edited for length and clarity.

UNDARK — Can you describe what you see as a problematic relationship between doctors and patients?

BARBARA EHRENREICH — What was fascinating to me was how thoroughly the patient is depersonalized, especially if it’s a woman, and treated as if she was just dead matter — not a live, conscious person. I didn’t realize, for example, before I started working on this, that the first patient a young doctor sees in medical school is a cadaver. And it sort of sets the tone for the rest of it. There are better ways to do it. A cadaver is not a great representative of a living human being.

So they start from this idea that they are just dealing with some kind of lump, and it goes downhill from there. As for women, a big point of contention in the mid-20th century and for a couple decades afterwards was the handling of childbirth, which typically meant that the woman had pubic hair shaved. She was given an enema. And until we really started complaining, we were given knockout drugs — more or less anesthetized.

All of those things are not necessary. There’s no evidence basis for doing things like the enema or shaving pubic hair or the episiotomy that goes on after the baby has come out. It becomes about mastery, domination — if you look at what it feels like to the woman undergoing it.

UD — What is the relationship between medicine and science?

BE — Well, it’s often very tenuous. And that’s just something that has been brought to light increasingly since the 1970s, with the first proposals that medicine should be evidence-based. Now that phrase in itself is kind of funny because what was it based on before, right? Superstition? Male intuition? I don’t know. But one procedure after another has been subjected to careful statistical analysis and found not to be as advantageous as advertised — or not at all.

One of the things that’s changed in my lifetime is the annual exam. There’s no evidentiary basis. No reason to think that people who have them live longer than people who don’t. It’s a ritual; not a scientifically based intervention. And then that difference of treating people as if they were just lumps of dead matter also interferes with any truly scientific approach to care. If you were really being scientific you’d listen to the patient, you’d regard the patient as an agent, an actor, someone with information.

I [had] this strange experience where my primary care doctor, out of the blue, decided he needed to test me for lung capacity. Anyway, [he] had some kind of new device to measure your lung capacity, how well you’re breathing, and the idea was I should blow into this, and I kept blowing into it. And that little device wasn’t registering anything. I was alive. I was somebody who works out a lot. Does a lot of cardio. But he was much more interested in what this stupid gadget was saying than anything he could find out from me just by looking at me. So that’s not too impressively scientific.

UD — You write about the problem of overdiagnosis, especially in the realm of breast cancer, pointing out that increasing mammographies doesn’t increase survival rates. Why not?

BE — The United States does far more mammograms than most countries. They do not do anything to prevent breast cancer. The idea is that maybe they can find lumps when they’re very, very small — which sounds very sensible. One problem is that a lot of those lumps aren’t going anywhere. They’re false positives.

I described having a mammogram, described to me by the medical staff as a bad mammogram, and I freaked out because I’d already had breast cancer. But I went through some further steps, a sonogram and an MRI, and they said, “Whoops! That was a false positive. We’re just using this new system of mammography now, which creates a lot of false positives.” I said, “Well, you know, that could’ve gone on to a biopsy.” And the hospital would anesthetize for a biopsy. It could’ve led to treatment where none was needed.

The whole pink-ribbon culture expands up this obedience among women. “Yes, I must have my mammogram.”

And in between your mammograms, cancer could develop and a very fast-growing one and you wouldn’t know it. I’m saying you can’t feel safe with a negative conclusion either. The whole idea that all centers start small and then grow along some curve, some time plot, is not really that well established.

UD — You write that “the mind’s struggle for mastery over the body has become a kind of Mortal Combat.” How so?

BE — I first discovered it at the gym. Where it’s not “Oh, let’s go exercise and feel better with the results,” such as stress. Today, the language is very violent. You gotta crush your body. In my gym they have a new class called “shredding your body.” It’s “Can I master my body?” Can I dominate this kind of animal attachment that I might have? It’s very odd, and that ties into some class-based things. Most of the people who have gym memberships are probably in the upper 20 percent of income, and they’re probably more likely to be managers than to be front-line workers.

The idea is, if you can’t control your own body, how could you tell other people what to do? If somebody is fat — God forbid in our culture — then that’s taken as a sign that they cannot even control themselves. So why should they have a white collar job?

I started tracking [the idea of control] into science — those diseases that really represent a rebellion on the part of some of our cells against the entire organism. Most somatic cells don’t reproduce very much. But a cancer cell says, “Oh hey, let’s just go crazy here and reproduce.” And eventually, that’s what’s killing the body.

Then you have autoimmune disease, where your immune system turns against different organs in parts of the body. The thing that most fascinates me is macrophages — the front-line immune cells we think of as fighting the bad guys. But one of the things that recently shocked me was the discovery in the early part of this millennium that macrophages actually promote cancer. That they come right from cancer cells and allow cancer cells to metastasize, to go to other parts of the body. And to me, as somebody who studied macrophages in graduate school, this was devastating. I thought they were good guys.

There is no way, that we now know of, to get macrophages to do what we want them to do. As it turns out, the cells make some decisions for themselves.

You want to boost your immune system, right? Well, your immune system could turn against you.

UD — Patients are sometimes told to “think positive,” as if that will make a difference in the outcome of their illness. What do you think?

BE — Oh, I hate that, that’s why I wrote a book about that. That’s what’s called bright-sided. And what I hate about it, it’s not just that it’s not evidence-based, but that it blames the victim. If you have cancer and the outlook is not good and you somehow fail to be positive, then people around you can just get irritated at you. “Be positive and you’ll live!” Nonsense. You may need to express anger, sorrow, fear. And we just have a society that says that’s impermissible.

It’s more dishonest when you’re telling people that they have to be positive although they know they’re in advanced stage of metastasis — I mean they’re not feeling positive. You should just respect what they feel. Don’t tell them what to feel.

Hope Reese is a writer and editor in Louisville, Kentucky. Her writing has appeared in Undark, The Atlantic, The Boston Globe, The Chicago Tribune, Playboy, Vox, and other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I was surprised to see in her book “Natural Causes” that she thought “Gaia had not figured out how to correct for the profligate human consumption of fossil fuels”. As a scientist I find it hard to believe that she would not know that the earth operates in millions of years and I expect that homo sapiens sapiens, that most opportunistic species spreading throughout all of earth to the detriment of every other species, will simply be wiped out in time. The planet will look after itself, even if that means there are no humans left.

While I can appreciate Ms. Ehrenreich’s views, this article makes them appear rigid and unyielding. I would hope she is actually more open to debate and reasoning. Perhaps the editing makes her appear more one-dimensional than she truly is. Her viewpoint is very interesting and I respect her steadfastness, “get-off-my-lawn” approach to medicine. Be well.

Brilliant liberating book. My husband and I are clost to Ehreneich’s age with good insurance. We have been preyed on just because of that and have had an overabundance of useless tests- sleep apnea, wires going up veins-.total horror shows.I clicked all the boxes- meditation- fat free diets, hard muscle work-outs- yoga etc.

We are reading this book together and laughing every night at ourselves and the fecklessness of the medical profession and what fish we are and have been.

Episiotomy is given during the birth and not after. Shaving and enemas we’re laboring moms stopped 40 years ago.

I am sorry the author only met doctors who looked at her as a cadaver. My doctors saved my life.

I and my child are alive because if modern medicine and Big Pharma. The entire piece sounds like something written by someone who won genetic lottery

These thoughts are caricatures. While the lines capture some truths about medicine and life, they fail to capture the complexity of the deeper reality.

She likes the concept of evidence based thinking, but leaves out a lot of evidence in her oversimplified generalizations about the interactions on society and on health care.

She says doctors should listen, and I heartily agree that listening in medicine is a lost art, but by making her sweeping indictments in the way she presents them she herself is failing to listen.

There’s a point in there somewhere but some of her examples are misplaced, or she draws the strangest conclusions from them. For example med students are given cadavers to work with not so they can learn to treat patients like objects, but rather more that they are studying the fundamentals of human anatomy. Oh, and whatever newbie mistakes the med students they make wont kill anybody.

Thank you Barbara Ehrenreich..I’ve always appreciated your point of view.

For a deeper dive into the problems with breast cancer epidemiology see this award winning investigative series: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-one-renee-willards-story