Shared Fates: Vaquitas, Totoabas, and Fishing the Sea of Cortez

Javier Valverde grew up next to the sea, mesmerized by the thick schools of totoaba that swam near the shore. These silver fish can grow to more than six feet and weigh more than 200 pounds. Some days, the young Valverde would spot them jumping high out of the water. “They weren’t shy,” he recalled.

Decades ago, fishermen in the northern Gulf of California encountered a rich bounty of totoaba, sharks, and sea turtles that would transform the region into a fishing mecca. Today, species decline and political battles prevail.

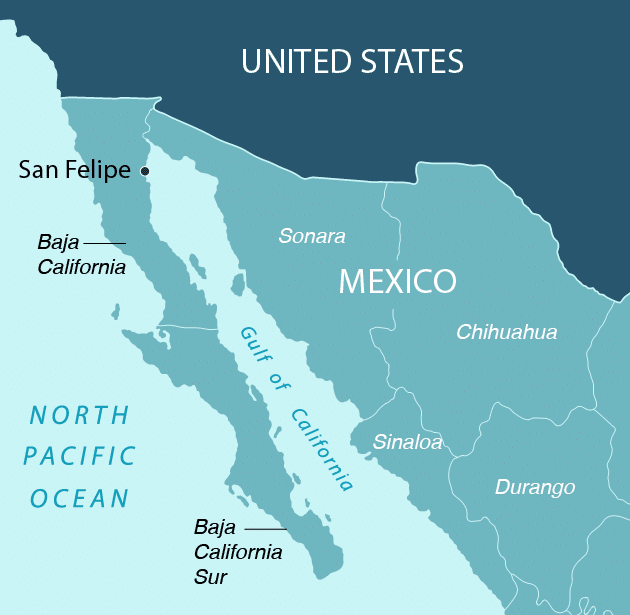

In the 1930s, Valverde’s father was among the early residents of San Felipe, a town in the Mexican state of Baja California, and situated on the edge of cactus-studded desert and sparkling ocean — the Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez. The hunt for the large drum fish had lured hardy fishermen to cross the Gulf to its northern reaches, where they encountered a rich bounty of totoaba, sharks, and sea turtles that would transform the region into a fishing mecca. By the time he was a teenager in the 1960s, Valverde was guiding tourists enticed to his village by a new hook-and-line totoaba sportfishing industry. Some fish were so big that, when held upright, they would have towered over the boy’s thin frame.

But by then, large mesh nets had proliferated across the Gulf. Commercial vessels, including shrimp trawlers whose nets indiscriminately scraped species from the sea floor, had capitalized on the largely unregulated sea bonanza. “We were no longer the only ones fishing,” Valverde said. “People were coming from all over to fish with bigger nets, bigger boats, and the fleet became very large, immensely large. And not everyone respected the sea.”

Today, the Gulf of California remains a productive if diminished fishery, contributing 54 percent of Mexico’s 2.2 million tons of commercial seafood in 2017, according to Mexico’s Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development. But those numbers belie a bitter struggle now underway here — one that has lawless poachers, economically strapped fishermen, international conservation groups, and feckless regulators squaring off over the value and purpose of this blue expanse. The battle is most vividly manifest in the fate of the vaquita marina, a captivating but rarely spotted species of porpoise, endemic to the northern reaches of the Gulf. In March, scientists declared that only about 20 vaquita remain, and the crisis has gained extensive media coverage.

But as the international campaign to save the vaquita has become increasingly pitched, so too has the plight of traditional fishing communities like San Felipe, which is situated in close proximity to the vaquita’s sole habitat. Locals say fishing bans meant to protect the vaquita have done little to quell tensions. Poachers still operate with abandon, they say — many of them in pursuit of the dwindling totoaba and its coveted swim bladder, which is sold in China for its supposed medicinal powers. Meanwhile, the system of compensation set up to support idled anglers in the region has itself grown scarce, and under the leadership of Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, many fishermen say they have not received any payments since mid-January, leading to protests.

The crisscrossing battle lines now have fishermen like Valverde struggling to make ends meet in a region that owes its very existence to a generous sea — their fates now intertwined with those of the vaquita, the totoaba, and a wide cast of national and international stakeholders. As it stands, restricted access to vaquita habitat keeps local pangas — small fishing boats — sitting motionless in residents’ yards, instead of dockside and on the boardwalk where they had long dotted the sand.

“The government has closed the sea to us,” said Valverde, a mustachioed, slender man in his 70s. “Fishing is our livelihood; what do they expect us to do?”

Mexico first began taking steps to protect the vaquita decades ago. In 1996, the government established the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) to develop an action plan that would take both scientific evidence and the economic impacts of conservation into consideration. In 2005, it established a vaquita refuge where all use of gillnets — vertically hung nets designed to trap fish by the gills — was prohibited. This was followed by the rollout of a voluntary program to help fishermen switch to using safer gear, or compensate them for not fishing in the refuge — or even leaving the industry all together.

These efforts have had little effect — in part due to lax enforcement and a dearth of economic opportunities — so, in 2015, Mexico banned gillnet fishing within the animals’ range for two years and entered into an agreement with local residents. Fishermen from San Felipe and a neighboring town agreed to remove about 800 pangas from the water. This would allow the federal government to clear the sea of nets and develop alternative fishing gear. In return, the government was to pay about $53 million to some 2,500 people employed in the fishing sector.

By 2017, Mexico had made the ban on gillnets permanent, with the exception of those used to catch corvina, a whitefish similar to sea bass. But today, pressure from conservationists persists. “Over the past 20 years we’ve seen Mexico continue to propose new programs to save the vaquita, and over and over we’ve seen exactly the same thing: that those have failed due to lack of enforcement,” said Sarah Uhlemann, international program director at the Center for Biological Diversity. Her conservation group estimates that in 2017, more than 1,400 tons of fish and shrimp caught with the banned gillnets, and worth about $16 million, were exported to the United States.

Uhlemann’s group, along with the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Animal Welfare Institute, sued the Trump administration last March for non-compliance with the Marine Mammal Protection Act’s “foreign-bycatch provisions” to protect the remaining vaquitas. This culminated in a U.S. import ban on shrimp and other seafood caught with gillnets in the region. Some fishermen now worry that this ban could be expanded nationwide.

All of these measures have taken a toll on the fishing sector. A lack of feasible alternative fishing gear and an explosion in the trafficking of totoaba swim bladders have drained the community’s lifeblood. The embargo, which applies to all products caught with gillnets within vaquita range, is one more obstacle, said Ramón Franco Díaz, who leads a federation of fishing cooperatives in San Felipe. “These are dark days for those of us who fish legally,” he said. “By law we cannot work, but those who fish illegally continue to do it, embargo or not.”

In fact, despite military and non-profit patrols that include drones and speedboats, poaching is booming. Criminal elements use the illegal gillnets to capture totoaba for its profitable swim bladder. Poachers furtively dry the gas-filled organ that helps the fish stay afloat in water and then ship it to China, where people pay up to tens of thousands of dollars for its purported aphrodisiac and healing properties.

Even when Valverde’s father first plied the gulf waters angling for totoaba, the fish bladder had been harvested for export, as well as to satisfy the region’s sizable Chinese population, who had immigrated to work in the agricultural fields. As a youngster, Valverde sometimes saw swim bladders laid out on the beach, drying in the sun. A handful of well-known locals used to sell the organ, he said, but nobody got rich off the trade.

He also never witnessed the totoaba carnage that now pervades the Upper Gulf. The fish carcasses rot on shore and float listless at sea, their guts violently ripped open. “Poor things,” Valverde said, sitting on his front porch with a somber expression. “What they’re doing with the totoaba now is an ecological crime.”

Franco Díaz figures that these days, totoaba poachers annihilating the species use upward of 500 illegal pangas in vaquita habitat. He said that’s about four times more than when the fishermen were still working. Further, a report by the Center for Advanced Defense Studies documented a link between the illegal totoaba trade and drug traffickers. The Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit concluded that the illegal trade has become so rampant that Mexico will only be able to rein it in with help from other countries.

None of this is news to San Felipe residents, who say that signs of drug traffickers began to emerge in 2012. Although fishing restrictions kept tightening for the sake of vaquita, locals couldn’t help but notice the outsiders who streamed into town with new fishing boats and new trucks. Two years later, a member of the Sinaloa cartel was murdered north of San Felipe, confirming the cartel’s ties to the totoaba black market.“It’s a very critical situation. We are worse off than when we stopped fishing,” Franco Díaz said. “Criminal organizations have taken over the Sea of Cortez.”

For all the attention bestowed on the vaquita in recent years, it remains an evasive, mysterious animal. Modern science first recognized the cetacean in the late 1950s through recovered skulls. A live vaquita wasn’t documented until the 1980s. Most of what scientists knew then came from dead specimens that washed up on shore or perished entangled in gillnets. Scientists say the blunt-nosed vaquita, or “little cow” in Spanish, may be the next marine mammal to go extinct. With dark patches around the eyes and dark outlines around the mouth that mimic an ever-present smile, the vaquita has become a captivating symbol for the human-triggered plight of vanishing species around the world.

In 1997, a vessel with a team of Mexican and American scientists conducted the first comprehensive survey of the vaquita’s abundance and range. Jay Barlow, a senior scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who was aboard the vessel, said the mammal was found only in the northern Gulf. “We estimated that there were 500 to 600 animals left at that time,” he said.

By 2015, that number was down to about 60. Now, scientists say there are only about 20 — possibly even less. “I’ve heard people say that we should just let the vaquita die with dignity,” said Barlow. “Well, I don’t believe that there’s any dignity in extinction. It’s a loss for everyone on this planet when we lose another species.”

In late 2017, an international team of scientists entered into uncharted territory: an attempt to capture for breeding the world’s most endangered marine mammal. As part of a $5 million mobilization, they built a care center and sea pens to shelter vaquita. But the team decided to suspend the operation after capturing two vaquita, a juvenile that was released after showing signs of stress and an adult that declined after being placed in a floating pen and ultimately died upon release. “When you dedicate yourself to conservation, when you dedicate yourself to marine animal care, you know that there is a great risk,” said Mexican mammal expert Ricardo Rebolledo. Though some had feared that vaquita might perish if plucked from the wild, he believed it was a chance worth taking.

Morning had just broken in San Felipe, and 11 pangas were leaving the dock carrying about 20 fishermen. They were on an eight-hour mission to mark the location of abandoned fishing nets for eventual destruction. Abandoned or lost nets, some large enough to trap whales, hang underwater like porous panels that snare vaquita, totoaba, turtles, sea lions and a host of other marine species. On this nascent fall day, the task of these men was to mark the nets’ location with buoys.

Armando Castro called out orders into a two-way radio, leading the way in the salty breeze toward the Narval, a 135-foot vessel in the distance. A short time later, Castro transferred his passengers: me, my photographer, and a federal environmental inspector. After we boarded the Narval, Castro dispersed with his fleet of pangas deep into vaquita territory in search of redes fantasmas — ghost nets — left behind, mostly by poachers, in the still of darkness.

It’s an unusual, somewhat discomforting job for men who have spent their lives tossing nets into the sea, hoping for a good catch. They worked in tandem with the Narval and a second vessel operated by the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. When the fishermen marked a location, they radioed the nearest of the two large boats to retrieve the nets. As of last year, more than 1,200 nets had been pulled from the water.

As he navigates the deep blue waters of the Upper Gulf, Narval captain Francisco Javier Melchor says the prevalence of nets left behind astounds him. “The amount of ghost nets in the water is incredible. It’s rare to not find any when we go out,” he said from behind the steering wheel on the bridge of the ship. The large windows before him framed ocean and sky in a wealth of blue hues as he searched for pangas through his binoculars.

Around 10:30 am, the first radio call came in to the Narval, prompting a flurry of activity. Men donned yellow fisherman overalls. In a tug-of-war with the sea, they used a grappling hook to retrieve a water-heavy, worn-out gillnet. This time at least, there were no live or dead animals for the federal inspector to document.

Want more Undark? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter!

Claudia Cecilia G. Olimón, executive director of Pesca ABC, a San Felipe-based civil organization that develops and promotes the use of sustainable fishing gear, coordinates their retrieval. “What dismays and surprises us,” she said, “is how, despite the fact that the eyes of the world are now on the Upper Gulf of California — and there are so many authorities deploying their personnel — illegal nets keep turning up. How do they get there?”

Locals say that when poachers are in the water, authorities often look the other way in exchange for cash. The practice is illegal, but the so-called mordida remains ingrained in the culture, despite attempts to eradicate it. Even when poachers are detained, locals say, they quickly gain their freedom and return to the sea.

Regrettably, Valverde said, bribes are a way of life both inside and outside of government. “It pains me to see what’s happening to my town.”

“I’ve been fishing my whole life,” said José Luis Romero, who was born in San Felipe nearly 60 years ago. “My father was a fisherman and captain of a ship. When I was a kid, I used to go to the ship after school.”

Standing inside a whitewashed government building one day last summer, Romero had just learned that he wouldn’t receive his compensation — it had been three months since he last did. Irregularities have plagued the government’s distribution system from the start, and today, fishermen say the payments have stopped altogether.

Romero wore a baseball cap. He had a long, untamed gray beard and furrowed eyebrows. He took a deep breath, rubbed his eyes in frustration and lit a cigarette. He hasn’t fished in several years and his inability to put food on the family table gnaws at him. He would gladly give up the government money for a chance to cast a net again in favorable tides, he said, like he did before the ban.

Although many locals are skeptical that the elusive vaquita even exists, Romero said he’s caught fleeting glimpses of the animal as it surfaced to breathe. He was among a group of conservation-minded, or resigned, fishermen who volunteered to try alternative fishing nets during the government’s early attempts to test and approve for use more sustainable fishing methods that can allow vaquita to reach their full size of approximately five feet, 120 pounds. “We wanted to do something,” Romero said. “I would like my grandchildren to see the small animal someday, but given the current situation, I don’t know if that’s possible.”

With the payment he got for giving up his gillnet, he bought a new panga and a small trawling net to catch shrimp, a lucrative export for Mexico. Like the other fishermen who agreed to the conversion, he didn’t care for the new fishing gear. “It’s very destructive; it drags wildlife and everything else from the bottom of the ocean, but supposedly not the vaquita. It didn’t catch much shrimp, all we did was waste gas testing it.”

Romero was always willing to test whatever potentially sustainable gear was brought forth, he said, but said the nets don’t yield much. “They’re not profitable enough,” he said, “so you can’t make a living off them.” As long as government officials continue to make decisions from behind their desks, without effectively tapping the expertise of the fishing community, solutions will be hard to grasp, he said.

Without his compensation, Romero and his wife, Bertha Reyes, survive on what little she makes helping out at their daughter’s thrift store. Sometimes he earns a bit of money placing acoustic devices in vaquita habitat to record their sounds. By listening to the porpoise’s rapid series of clicks, scientists can pinpoint their location.

In addition to living with financial uncertainty, fishermen also feel unfairly targeted for criticism. “Many NGOs have dedicated themselves to opposing the fishing sector without trying to understand the reality of what’s happening in the community,” said Franco Díaz, the leader of the fishing cooperatives. This has stirred local resentment, especially against Sea Shepherd, whose vessels have been a flashpoint since they first arrived in 2015.

Some locals view the organization as a foreign invader and protest its sometimes-confrontational tactics. For example, the Sea Shepherd was blamed when a man who was illegally fishing one night was spooked by one of the organization’s large vessels and went overboard. On another occasion, dozens of angry fishermen allied with an aggressive faction of the fishing sector burned an empty fishing boat bearing the group’s name and demanded it leave the Gulf of California. Suspected poachers have fired shots at its vessels and ambushed a ship crew despite the presence of federal police officers and soldiers posted onboard. The animosity is perplexing to Patricia Gandolfo, a former Sea Shepherd campaign leader. “We are here only to remove illegal nets and nothing more,” she said.

Still, the reality is that a complicated web of factors has coalesced to the detriment of both vaquita and fishermen. As time wears on, some of the unemployed say they’re tempted to scurry off into forbidden waters late at night to catch a totoaba. A kilogram of its bladder could fetch about $2,500 locally and help ease financial burdens.

Those financial burdens are not simply due to untimely payments, said Olimón. Even when there is government compensation to go around and many fishermen do get fairly compensated, others have been “left with nothing.” Most affected are the lowest-paid fishermen, entitled to just $420 a month. This situation stems from the fact that some payments end up going to people not personally engaged in the fishing sector. The unbalanced payout has marked deep divisions among local residents — divisions that are amplified as totoaba poaching surges in the absence of economic alternatives.

The fishermen’s plight reverberates throughout the town.

On a balmy day last March, the sun bathed San Felipe in pleasant warmth that drew people to the strip of mom-and-pop restaurants and tourist shops along the waterfront. A few people lounged at outdoor tables, their gazes fixed on the lonely sea on the other side of the street. Not far away, a cluster of 10 businesses with boarded-up windows hinted at a bleeding economy.

“There’s not much tourism these days,” said Martin Romo, a restaurant owner. Instead of buying the prime shrimp that local fishermen used to catch in the waters just in front of his restaurant, he must now order it from the state of Sinaloa and pass the extra cost to his customers. Perhaps more than the disappearing seafood, he said, the combined presence of the military and criminal elements keeps tourists away.

“What’s happening here isn’t just bad for fishermen, it’s bad for all of us,” Romo said. “It’s killing San Felipe.”

About 150 miles to the northwest, Conal David True strolled through his small hatchery at the Autonomous University of Baja California in Ensenada, Mexico. An oceanographer and professor, True for two decades has spawned and raised totoaba. On this day, he stood near a giant tank with a small glass window through which close to 20 large totoaba could be seen swimming in circles.

Oceanographer and professor Conal David True has been spawning and raising totoaba for decades. “The idea here is to try to supplement the wild population and try to promote and develop aquaculture in the Upper Gulf,” he said.

Visual: Lourdes Medrano for Undark

“The idea here is to try to supplement the wild population and try to promote and develop aquaculture in the Upper Gulf,” said True. He lamented the dire state of the region’s fishing industry, but spoke enthusiastically about the totoaba’s history and steps being taken to protect its stock. Doing so can relieve pressure for the wild population, he said.

Initially, his program focused on totoaba aquaculture. In the 1990s, it went further, introducing an annual release of juveniles into the species’ habitat. In recent years, his team has released as many as 128,000 at one time.

The state and federal governments are funding a major expansion of the breeding program. According to True, it will include a new state-of-the-art structure at the cost of about $4.4 million that will allow the production of up to 1 million hatchlings a year and boost restocking efforts. This will enable the campus hatchery to produce hatchlings for up to five farms in the Upper Gulf region that can employ residents. Farm-raised totoaba is already sold in some of Mexico’s restaurants. The meat may not be exported, and totoaba hatcheries are required to help repopulate the species in the Upper Gulf.

Despite the damage that people have inflicted on totoaba habitat, each spring the fish continues to spawn in the nutrient-loaded Colorado River delta before migrating back south along the Gulf, while juveniles stay behind with the vaquita. In these murky, shallow waters, the fragile fate of the two species becomes one.

There is talk of bringing back a hook-and-line totoaba fishery to revive the local economy. Early last year, Mexico’s government announced it was considering legalizing the totoaba trade, a prospect that has widespread support from the fishing sector.

True cautioned, however, that this won’t be a quick fix. Regulators still need to determine whether the population is healthy enough for this, and then regulations need to be implemented to allow a fishery. The process can be lengthy. Further, said True, San Felipe needs a more integral solution that includes more sources of employment as well as more tourism activities.

Out on the porch of his house, Javier Valverde says he likes the idea of legalized totoaba fishing. “It seems like it’s the only option for not having to use a gillnet,” he said, his speech melding in the air with the crow of a rooster and the barking of a dog. “Totoaba fishing seems like a good alternative to shrimp, which they don’t want us to catch because we supposedly kill vaquita.”

He views a possible totoaba sportfishing industry — like the one he grew up with — as a viable solution that can ease the region’s economic woes and ensure a healthy animal stock if the government sets individual quotas per season, with checks and balances along the way. “Let’s say each fisherman is allowed to catch 10 totoabas per season,” he said. “We’re obviously going to keep the best ones and we can liberate the rest. Then we can spend the rest of our time taking care of our sea and reporting those who don’t comply.”

Many view totoaba aquaculture not only as vital to preservation of the species, but also as a potentially sustainable resource for Upper Gulf communities. The notion gained favor at a spring workshop devoted to creating community-development strategies. That forum united divergent voices, but good ideas take time and funding to implement. Meanwhile, idle fishermen are getting restless.

Valverde thinks about totoaba: As the days of spring wane and the females lay their eggs, the fish will head to deeper waters — assuming they evade the poachers’ nets. What will his town be like when they return in coming years? That question fills him with uncertainty, but he holds out hope that the days of making an honest living fishing close to home will return.

“God willing,” he said, “I will keep fishing until I can no longer physically go out to sea.”

This story was produced in part with support from the Fund for Environmental Journalism of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Lourdes Medrano is a freelance journalist based in Tucson, Arizona. Her work, centered on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, has been featured in various print and online publications, including The Christian Science Monitor, The Washington Post, Wired, The Atlantic, and more.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Can I link to your article on our website and newsletter. We have been working on the vaquita for 9-10 years.

Thank you for your consideration.