Heartburn Gave My Dad Cancer. What About the Rest of Us?

Nearly 20 years ago, my family got together in the Finger Lakes region of New York for Thanksgiving. The last night of our trip, we went out to a local tavern for dinner. I can’t remember if my father ordered fried shrimp or fried chicken. I do remember he didn’t eat it because he said he didn’t feel well. When I looked at him across the table, he looked gray.

Afterward, my parents returned to their home in Florida, and about two months later, in February of 2001, my father had trouble swallowing a glass of orange juice. He went to the doctor, they conducted tests, and he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. I recall my sister, trying to be helpful, sent out an email to the family with a link to an American Cancer Society webpage that essentially said esophageal cancer, while rare, is difficult to detect, and by the time symptoms arise, it’s often reached an advanced stage where it’s become difficult to treat.

I cried the entire weekend, until my eyes were swollen. I was very close to my father. He was my best friend.

His doctors were hopeful and came up with a plan: chemotherapy and radiation to shrink the tumors and then surgery two months later. The surgery happened in May, but by June, tumors were erupting on different parts of his body, both inside and out, like mosquito bites. A large one emerged on his chin, which we called a nipple.

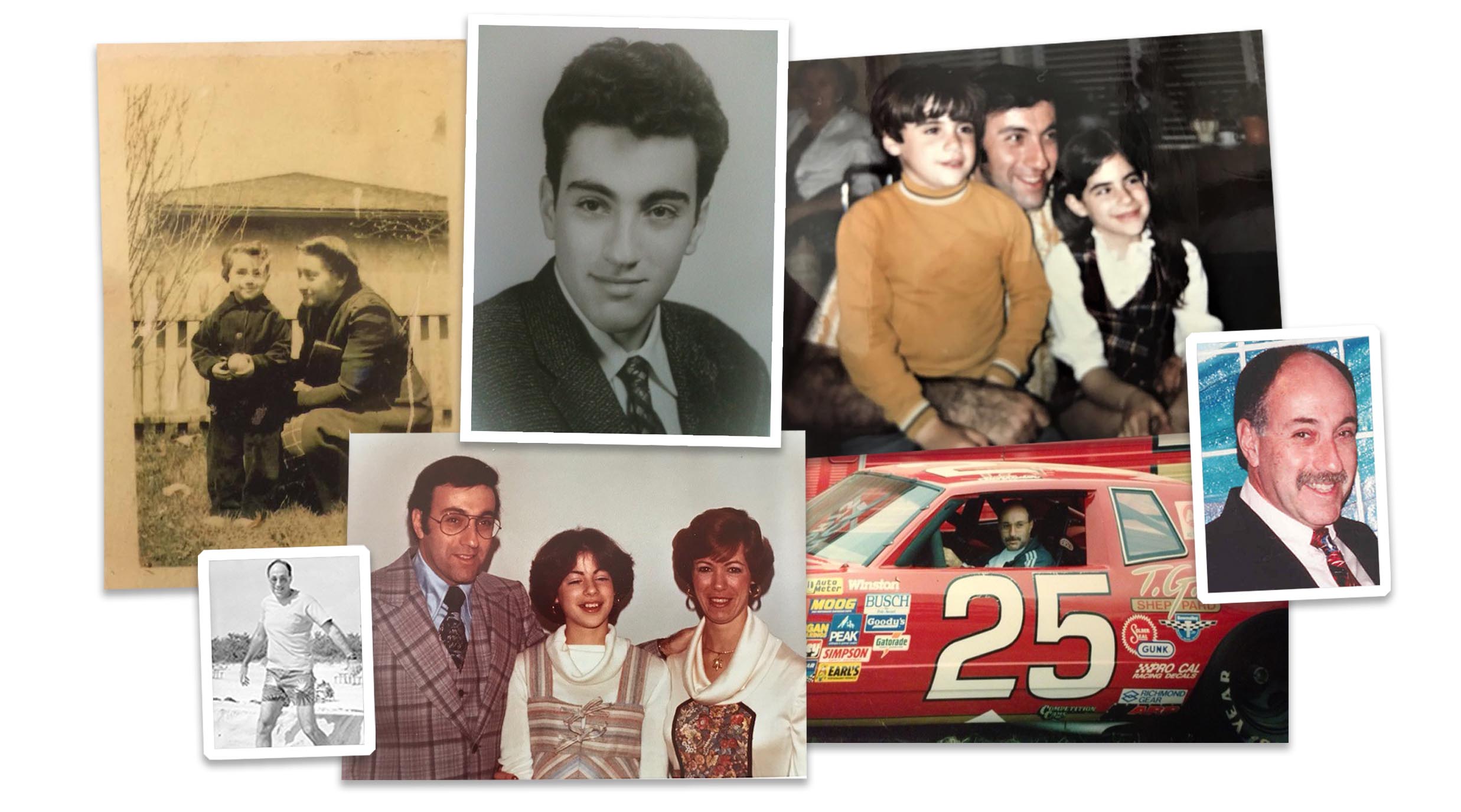

In February of 2001, my father, Edwin “Eddie” Chesler, had trouble swallowing a glass of orange juice. He went to the doctor, they conducted tests, and he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. He wouldn’t last a year.

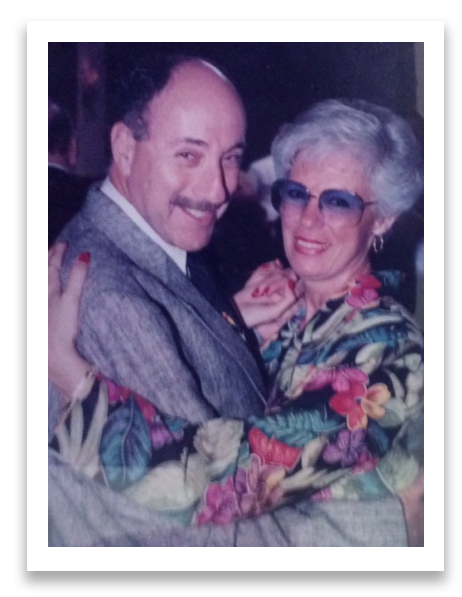

Visual: Courtesy of the Chesler family

As a last-ditch effort, my father enrolled in a Phase I clinical trial at Memorial Sloane Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. He would commute into the city a few times a week from Long Island, where he was staying with his sister. By September, doctors told him the program wasn’t working. Three months later, he was dead. He was 62.

The doctors attributed his cancer — adenocarcinoma, which usually occurs in the lower portion of the esophagus — to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) — basically, chronic heartburn. When the sphincter between the stomach and the esophagus is weak or doesn’t function properly, stomach acid can move into the esophagus. But the esophageal lining can’t tolerate this repeated exposure and so it can begin to change, cell by cell. In that metamorphosis, cell division can go awry and tumors can erupt and wreak havoc, first in the esophagus, then the lymph nodes, and eventually, the lungs, the liver, and the brain.

It’s been 17 years since my father’s death, but as I approach the age at which he died (I am now 55), I fear the thing that got him will get me. That’s because I, too, suffer from acid reflux — and so do many other Americans. One might even call it an epidemic of heartburn, with more than 60 million Americans experiencing reflux at least once a month, according to the American College of Gastroenterology. Some studies suggest more than 15 million Americans experience symptoms of heartburn every single day.

Globally, most esophageal cancer is designated as squamous cell carcinoma, which typically occurs in the upper and middle part of the esophagus and is associated with alcohol and tobacco use. The same used to be true for the U.S., but starting in 1997, American esophageal cancer patients, on average, became much more likely to be diagnosed with adenocarcinoma, which is associated with GERD. In fact, according to the National Cancer Institute, esophageal adenocarcinoma is one of the fastest-growing cancers in the country. In 1973, just 3 people in a million had adenocarcinoma in the U.S. In 2014, that rate was 26 people per million, representing an increase of more than 600 percent.

Dr. Michael Ebright, a thoracic surgeon based in Stamford, Connecticut, said many of his patients come to him because, like my father, they are having trouble swallowing. “Some patients come in unable to swallow their own saliva,” he said. I imagined my father being asphyxiated from the inside and shuddered.

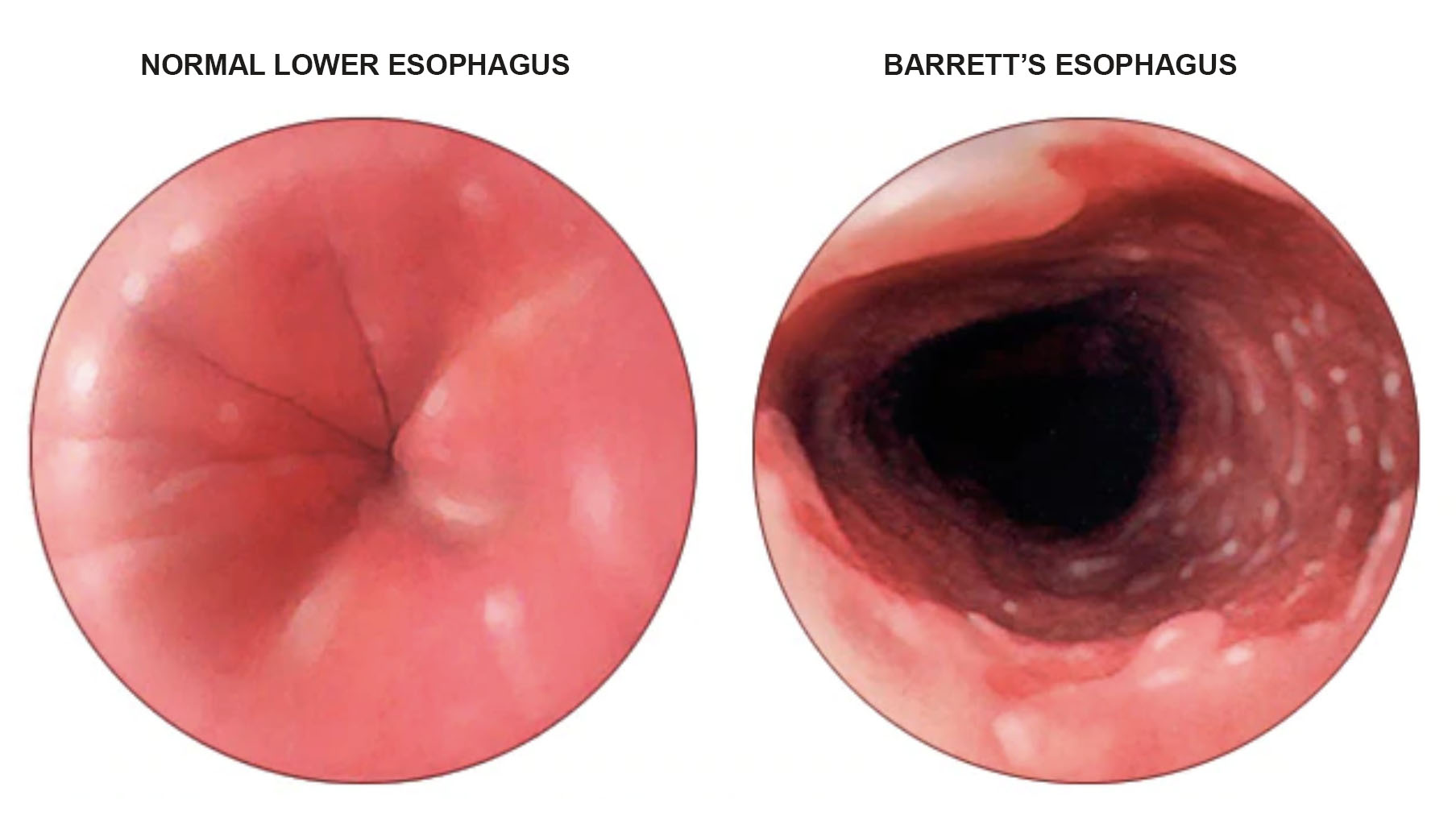

One of the most common risk factors for getting esophageal cancer is developing Barrett’s esophagus. Barrett’s is when the esophagus is exposed to so much acid, the lining, or mucosa, changes on a cellular level to that of the lining of the stomach or intestines, which is accustomed to an acidic environment. Biologically, the progression — called metaplasia — looks like this: First, the squamous cells that normally line the esophagus are replaced by glandular cells. These are normal cells; they’re just not typically in the esophagus. This can give way to dysplasia — meaning these glandular cells no longer look normal because their DNA has actually changed. Neoplasia, the next stage in the progression, is when the cells have become so distorted and fragmented, they’re barely recognizable. From here, they can begin to spread.

Not everyone with GERD develops Barrett’s — about 10 percent, Ebright estimated.

And even if they do develop it, they face less than a 1 percent chance per year that it will progress to esophageal cancer. Still, data from the National Cancer Institute shows the incidence rate of esophageal adenocarcinoma has increased for all age groups 30 and older since the 1970s — though the disease skews heavily toward older white men, while squamous cell carcinoma remains more common in African-Americans. For patients of my father’s age, the incidence rate increased five-fold from 1975 to 2015. While it seems clear to most doctors that it is linked to rising obesity and poor diet, that doesn’t fully explain the rise.

“There’s also some other risk factor that we’re not detecting,” Ebright said. “Maybe more than one risk factor that we’re not detecting, that’s most likely causing it. We just don’t know the answer.”

The mystery has millions of Americans desperately buying and trying all manner of pills and pillows and chewing gum in search of relief for symptoms that, in a non-trivial and growing percentage of cases, are not just uncomfortable, but potentially deadly. It also has dozens of researchers now trying to sort out the mechanics of this fast-rising cancer — with theories zeroing-in variably, and however tentatively, on the long-underappreciated bacterial ecosystem in our guts, and even the very medications designed to treat reflux in the first place.

Even though doctors have reassured me that I’m a low risk for esophageal cancer, I can’t help but worry. I get heartburn — often. When I swallow food, it sometimes seems to stall at the back of my throat before going down the chute. And I know renegade acid has clearly entered my esophagus because my dentist tells me it’s been affecting my teeth.

To date, the full story behind this malignant boom remains elusive, but like so many other Americans — and given my father’s fate — I’m eager for insight and reassurance.

I decided to turn to Russell Hales, a radiation oncologist who specializes in esophageal cancer at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, for some answers. When I walked into the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, which houses his office, I was immediately saddened by the idea of people going in there with high hopes of kicking the disease, only to die anyway. I remembered when my father was first diagnosed, I sat in a park outside my office with an ex-boyfriend who worked nearby. His father had died of cancer several years earlier.

“These doctors make you think they can save them,” I recall him saying, “but they can’t.”

I was horrified. What a bad way of trying to cheer someone up, I thought. I attributed it to his bitterness about his own father.

When I got up to Hales’ office, we talked about how acid wouldn’t necessarily be problematic if it remained in the stomach, but when the muscular ring between the stomach and the esophagus, called the lower esophageal sphincter, doesn’t function properly, acid can enter the esophagus and irritate its lining.

It’s common knowledge to heartburn sufferers that certain things can compromise the functioning of this sphincter, from caffeine, alcohol, and smoking to obesity, pregnancy, and a hiatal hernia. But Hales said the sphincter can also relax if the body is producing too much cortisol, a steroid hormone that regulates a wide range of processes throughout the body, including metabolism and the immune response, and is released when the body is in stress. Cortisol’s effect on the sphincter is so predictable, when Hales writes a prescription for steroids, he also prescribes an antacid because he knows the patient will wind up with heartburn.

Hales reiterated the risk factor of obesity for esophageal adenocarcinoma. I told him I must be the exception, then. “What do you mean you’re the exception? You’re not going to get this, okay?” he replied. I’d forgotten.

We talked about how squamous cell and adenocarcinoma have different risk factors and response rates to treatment. “Adenocarcinomas have a higher risk of spreading,” Hales said, “while squamous cell carcinomas tend to cause more problems locally.” I asked which was better.

“Well, they’re both problematic,” Hales said. “When it’s all said and done, you can die of local disease or die of distant disease. It still is going to be a problem.”

Another difference between the two is the profile of the person who gets it. While not wanting to generalize too much, Hales said the person who gets squamous cell cancer is usually thin, a heavy smoker or drinker or both, and tends to have had more medical problems coming in because they probably waited too long to address them. They are the type of person who puts “duct tape over the ‘service engine soon’ light in the car,” he said.

“By the time they get to see me, they have a really advanced disease here,” he added.

Asked to paint a picture of patients presenting with adenocarcinoma versus those with squamous cell, Hales offered some broad sketches based on risk factors like weight, smoking, and alcohol consumption: “The adenos are well-dressed, they’re a little younger, they’re a little heavy set,” he said. “They look like business guys that got a little pudgy, you know? Or a lot pudgy. They’re like Donald Trump.” The squamous patients, on the other hand, tend to be skinnier, Hales said. “Again, I don’t mean to stereotype here. They’re going to tend to smell of cigarette smoke. Sometimes, there are alcohol dependence issues we have to work on.”

Of course, Hales added, these sorts of caricatures oversimplify what are profoundly complex diseases that can impact young and old, and people with and without these risk factors. “Most cancers are random events,” he said. “Sometimes there aren’t simple answers.”

That wasn’t exactly reassuring, but I had more questions. What about antibiotics, I asked? I remembered when I was first diagnosed with reflux 25 years ago, I had been on antibiotics for the preceding six months to treat a recurring bladder infection. Could our famous overuse of antibiotics also play a role in the rise of esophageal adenocarcinoma? Hales said he would not put them among the top risk factors right now, but added that this could change. “I want to be clear. Ten years from now, I may be saying something different, but all I can report is what’s in the data, and right now the data shows a small association with antibiotics,” he said.

A couple of studies have hinted at this association with esophageal and other cancers, but the evidence so far is thin — and even Ben Boursi, an expert in clinical oncology and radiotherapy at Sheba Medical Center in Israel and a co-author on those studies told me that making a connection between esophageal adenocarcinoma and antibiotics would be a “giant leap.”

Before returning home to New Jersey from my visit with Hales, I took a walk by Baltimore’s Inner Harbor and sat down on the stairs in front of the Maryland Science Center. I stopped and looked around me. A bunch of school children ran out of the museum toward the harbor, and a couple of adults followed, as one yelled, “Don’t go in the water!” Two of the three were overweight. A heavyset man rode by on a bicycle. Two policemen drove by in a golf cart that said Baltimore Police, both overweight. A group of women walked by in sneakers. Overweight. A handful of people walked by eating ice cream, some with little bellies protruding through their shirts.

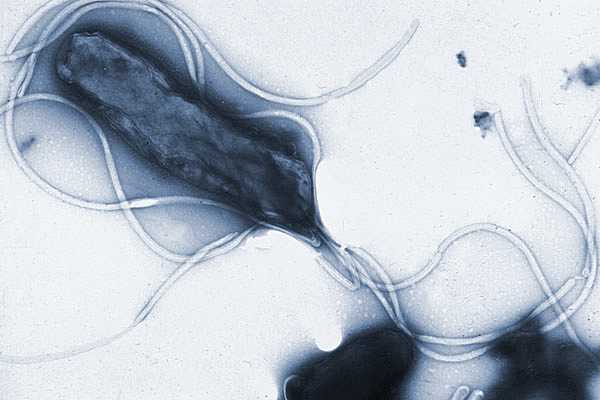

There’s no question that we are getting fatter, and that seems to have a clear link to the rapid rise in chronic heartburn-related cancer. But the fact that obesity can’t explain every case of esophageal adenocarcinoma still worried me, so I reached out to Martin Blaser, who spent the last decade studying the microbiome of the gut. Blaser, a microbiologist and director of the Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine at Rutgers University, believes the rise in esophageal adenocarcinoma is at least partly due to the loss of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, or H. pylori.

In his book, “Missing Microbes,” Blaser theorizes that our bodies contain ancient microbes, that these microbes serve beneficial functions, and that altering that ecosystem has consequences. “One of the consequences,” Blaser said, “is the fall in some diseases, like stomach cancer, and the rise of other diseases, like adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.”

This is due in part to H. pylori, he said, “which was the dominant organism in the human stomach and over the course of the 20th century has been gradually disappearing.” While that loss likely began before antibiotics were even discovered, Blaser said, the medications do contribute to the disappearance of H. pylori, and he believes this loss is driving esophageal adenocarcinoma.

“I’m going to make a very long story short,” Blaser said. “I think the rise in esophageal cancer began probably in the 1960s and the 1970s, and I think the first hit was the loss of Helicobacter pylori.”

Blaser said that in the past, when everyone had H. pylori, “by the time people reached the age of about 40, they just weren’t putting out a lot of acid anymore,” because H. pylori was killing the cells that produced it. “In the absence of H. pylori,” he said, “people are reaching 40, 50, 60, and they’re still putting out high amounts of acid.”

This is something that the human esophagus never experienced before, Blaser added. “By the way, the most important predictor of whether a person has H. pylori is whether their mother had H. pylori,” he said. “It’s passed down through the generations.”

Jason Mills, a professor in the Division of Gastroenterology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis who studies H. pylori, explains the foundations of the H. pylori-acid dynamic. In an email, he writes that the “bacterium colonized most humans in the world up until about a century ago, when less communal living and more hygiene made H. pylori colonization rates go down.” While H. pylori is good at surviving in an acidic environment — better than most bacteria — Mills explains, it still can’t handle the amount of acid a normal, healthy person produces in the main part of the stomach. H. pylori normally moves to the far end of the stomach where it’s less acidic, but in some people, its presence can “trigger events that cause acid secreting cells to die.” And when those cells die, H. pylori can spread into the body of the stomach and can cause gastric cancer.

According to the CDC, the bacterium still infects about two-thirds of the world’s population, mainly in developing countries, though most people do not experience symptoms.

“In populations where they have H. pylori, you have a distinct correlation of having a lot less acid,” Mills said in a phone call, though he emphasized that this trend does not mean that H. pylori will have a predictable effect in any one individual. Depending on where the bacterium lives in the stomach, it can actually also increase acid production.

Some researchers believe the rise in esophageal adenocarcinoma is at least partly due to the loss of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, or H. pylori, pictured here displaying multiple flagella.

Visual: Yutaka Tsutsumi, M.D.

But on average, Mills said, “the less H. pylori you have, the more likely you’ll have acid across your population. That’s for sure.” And if a population has more acid, the esophageal exposure to acid across that population increases.

So what’s killing H. pylori? The better sanitary conditions that come with life in the developed world is one obvious explanation. But the overuse of antibiotics, Mills said, speaking to me from the European Helicobacter & Microbiota Study Group where he was giving a talk, could also play a part. “My H. pylori colleagues here at the meeting do think increased antibiotic use might have a role in decreased H. pylori,” he said.

The irony in this, if true, is that the presence of H. pylori increases the risk of stomach cancer, which was the number one cause of cancer death in the U.S. up until the 1930s. That’s because when the bacterium is present, it can kill off the acid-secreting cells in the stomach, leaving a much less acidic environment. This in turn causes the digestive-enzyme secreting cells to undergo that sinister progression of change called metaplasia, putting the stomach at risk for cancer. In other words, Mills said, we killed off H. pylori, in part, to reduce stomach cancer, and we wound up with too much acid in the stomach, which puts the esophagus at risk for metaplasia and cancer.

“We’ve basically traded stomach cancer for esophageal cancer,” he said.

What puzzles cancer researchers, Mills said, is why metaplasia is a cancer risk. Mills helped organize a symposium on just this topic. He believes it’s a risk because in a hostile environment (acid and bile in the esophagus or bacterial inflammation in the stomach), mature cells revert back to fetal or embryonic cells, whose sole function is to reproduce. If they can figure out this reversion process, which Mills’ lab has called paligenosis, then they might be able to halt or reverse many types of metaplasias.

“Understanding how cells undergo paligenosis can help us figure out how to regenerate lost tissue, like insulin-producing cells,” Mills said, “and understand how the process goes awry when metaplasias don’t just repair but, for some reason, stay chronic and then even progress to cancer.”

Of course, as scientists try to figure out the cellular mechanisms, people with reflux are desperate to address their painful symptoms and will try all sorts of remedies. A woman in my writing group, Delia O’Hara, said she chews gum to alleviate her heartburn. Several small studies suggest there’s some truth to it. “I got rid of my GERD years ago by chewing sugarless gum for half an hour a day for some weeks,” she told me. “I forget how long it took. It comes back once in a while, and I chew gum for a week or so and it goes away.”

Health food stores, meanwhile, sell something called a raft-forming alginate, which is a mixture that expands in your stomach and forms pH neutral floating foam that sits atop the stomach contents like a raft. It slides up into the lower esophagus and creates a barrier, which prevents acid in the stomach from moving upward.

I interviewed a man in Queensland, Australia whose ingredient supply company makes dietary fiber from raw sugar cane by removing the sugar and grinding up the rest of the plant. The company, KFSU, originally intended to make functional fiber for basic gut health, but pharmacists began telling them that people were buying it to address their reflux or GERD symptoms. Why? KFSU’s managing director, Gordon Edwards, wasn’t sure, though he theorizes the fiber reduces the bubbling of acid at the top of the stomach.

When I’m having a bout of reflux, I drink apple cider vinegar and sleep on a foam wedge pillow to keep it at bay. I’m not sure why the vinegar works for me — the science is lacking — but I know why the wedge works: gravity. By keeping my body at a slight angle when I sleep, it keeps the contents of my stomach from moving into my esophagus, not unlike how a sewer pipe is pitched downhill from a house.

I interviewed a developer of a new and improved version of the sleeping wedge, a man by the name of Aaron Clark. Clark, a mechanical engineer, had been hired by Carl Melcher, a retired doctor who had chronic reflux and was diagnosed with Barrett’s. Melcher hypothesized that positional therapy could be used as an effective treatment for the disease. As Clark tells it, after several years of development and testing, the product morphed from a crazy contraption with hydraulics that would turn the user at night — like a rotisserie chicken — to a product that was stationary but enabled one to sleep comfortably on their left side, the best side on which to sleep to keep stomach acid from moving upward. The pillow has a hole in which one can place their left arm, like putting thread through a needle, so they can sleep comfortably and remain in that position all night.

By the end of the day, I had bought one of his MedCline pillows for a whopping $238 — though it was 40 percent off. I told myself $238 is not a lot of money to save the lining of my esophagus. I hoped Aaron Clark wasn’t peddling snake oil, but then even the most common treatments for reflux, namely, H-2-receptor blockers and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), are now receiving mixed reviews. H-2 blockers, like Zantac, Tagamet, and Pepcid, reduce the production of stomach acid but can cause headaches, constipation, and nausea. PPIs, like Prevacid, Prilosec, or Nexium are stronger, but recent studies have shown side effects such as infections, bone fractures, vitamin B12 deficiency, and, ironically, an increased risk of stomach cancer.

With the potential misuse of PPIs in mind, staff at the Lexington VA Medical Center in Kentucky implemented a PPI stewardship program, to get patients off of the medication in light of its overuse and adverse effects. Meanwhile, a meta-analysis in PLOS One in 2017 found PPIs don’t even necessarily protect patients with Barrett’s esophagus from getting cancer. The researchers concluded that “clinicians who discuss the potential chemopreventive effects of PPIs with their patients, should be aware that such an effect, if it exists, has not been proven with statistical significance.”

In fact, some researchers now believe PPIs are causing the very Barrett’s esophagus they are intended to prevent. In a 2014 opinion article in Frontiers in Oncology, researchers from Eastern Virginia Medical School proposed that a reduction in stomach acidity resulting from the prolonged use of PPIs may cause bile salts to ionize and mobilize upstream into the esophagus, suggesting that intestinal bile can induce metaplasia of the esophageal epithelium.

Not everyone buys this. Dr. Stuart Spechler, a gastroenterologist at Baylor Scott & White Center for Esophageal Diseases in Dallas, believes the newfound bias against PPIs is greatly exaggerated. “There are a lot of problems with the studies that are showing all these potential adverse effects of the PPIs and it’s very, very difficult to know exactly what the precise risk is,” Spechler said. “We do know that if you have severe reflux disease and you don’t take PPIs, your disease will come back.”

The side effects cited, like the bone fractures, cardiovascular disease, diarrhea, and strokes, are “all based on these weak associations in retrospective studies,” Spechler said, adding that “those kinds of studies can never establish cause and effect. They can only make inferences.” On the other hand, he noted, it’s virtually impossible to prove that PPIs are not causing these issues.

“We advise people to be very sure for the reason that you’re taking a proton pump inhibitor, and if you’re on it for a good reason, I think that these risks are really minimal,” Spechler said, though he added that the medication in general is overused. “I mean, there’s no question that many people taking PPIs should not be on them,” he said.

In certain cases, for those who want to try to get off PPIs, there may be surgical options.

If the problem is a hiatal hernia, it may be fixed surgically with fundoplication, where you use stitches to prevent the stomach from going through the muscle wall, then wrap the upper part of the stomach around the bottom part of the esophagus. This creates pressure to prevent food and acid from flowing upwards and if successful, most patients will be able to stop taking reflux medication. If patients don’t have a hiatal hernia and are not excluded by certain other conditions, doctors may put a magnetic ring, which is actually a string of beads, around the bottom of the esophagus that can tighten up the lower esophageal sphincter so acid doesn’t move upward. Both can help patients get off the PPIs, though Spechler says some people will eventually end up back on them after surgery.

For patients who already have Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia, there’s radiofrequency ablation, where doctors apply heat energy to the esophageal lining, or cryotherapy, where they freeze the affected tissue with liquid nitrogen in order to destroy it. The new cells that grow back should be normal.

If a tumor hasn’t yet invaded the muscle of the esophagus, you can often combine radiofrequency ablation with something called an endoscopic mucosal resection, where you actually remove the tumor without surgery by using a tube-like instrument inserted through the mouth. But if the cancer has progressed and is operable — which isn’t always the case — you might get an esophagectomy, to remove the cancerous tissue before it spreads.

My father had that surgery, and I recall they cut about 8 inches of his esophagus out (I was surprised at the time to hear we had a spare 8 inches to give up). The surgeon said my father may have difficulty eating, as his stomach was moved up and attached to the remainder of his esophagus. Turns out the problem wasn’t difficulty eating; it was that they left some cancer behind. When the surgeon came out to talk to us, he said the operation was a success — though he noted, almost as an aside, that he thought he saw a small black spot on my father’s lung but said it was probably nothing.

That night, we all smoked pot on my parents’ back porch and tried to remove from our heads any thoughts that contained the words spot and lung and rehearsed the line, “The surgery went well,” in a sing-songy tone, in case any neighbors stopped by to check on my father’s condition. We didn’t want them to know we were stoned, and we certainly didn’t want to cry.

That was in May of 2001. By June, my father had developed tumors on his arms, something Spechler says is not typical with esophageal cancer. When my father went back to his surgeon and told him the cancer had progressed, I recall him saying his doctor nearly fell out of his chair.

A month later, my parents called me at work to tell me my father’s cancer had spread to his liver. I cried out, “Noooooo!” like one might cry out as they watched their dog get run over by a car. I recall the man who worked behind me laughed because he thought I was joking. I ran downstairs and sat in a nearby park and stared up at the sky, watching the big puffy clouds float. One looked like a bunny, another, like a barking dog, and I thought, my father isn’t going to get to see clouds like this for much longer. He didn’t.

During Yom Kippur last year, I went to the Yizkor service, when prayers are said in memory of the dead. At my temple, they have musical interludes during Yizkor, and there was a young girl and her father playing together. She was a little chubby and looked nervous as she played her clarinet. She played mostly background harmony, like I used to do in my junior high band. While the boy who played first clarinet got to play the sweet melody of the violin solo in the prologue in “Fiddler on the Roof,” as third clarinet, I played mostly whole notes. You wouldn’t even know what song I was playing. There’s no honor in being third clarinet.

And yet during Yizkor, when the two finished their song, the father gave the young girl a fist bump, and I suddenly remembered my father, the cheerleader, and I flinched. I was awkward in junior high school, with frizzy brown hair and black oval glasses that I’d been wearing since second grade. But my father would stop to hear my tales of woe, how I’d been slighted by this one or that, and he’d remind me how interesting I was by just listening to me. In our pile of home movies, there’s one my father proudly took of me standing in front of our dining room table, with my thick oval glasses and a shag haircut that made my head like a crown of broccoli, and I’m playing whole notes on my clarinet, from a song that is unrecognizable.

The dilemma with GERD is when to treat someone with medication and when to opt for surgery. Far too many people rely on medication rather than exploring surgical options, said Dr. David Spector, director of bariatric and anti-reflux surgery at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital in Boston. For starters, PPIs don’t necessarily stop the esophagus from deteriorating, he said. Secondly, when you’ve got a condition that clearly has a progression, it’s vitally important to determine the proper steps are taken, before it’s too late. Spector said the talk at conferences for gastrointestinal surgeons these days is that something’s got to change.

“If we could stop the irritating factor, which is reflux, we could potentially stop the progression from reflux to Barrett’s to dysplasia to cancer,” Spector said.

“If we could stop the irritating factor, which is reflux, we could potentially stop the progression from reflux to Barrett’s to dysplasia to cancer,” said David Spector, director of bariatric and anti-reflux surgery at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital in Boston. Above, a detailed look at Barrett’s esophagus from the Mayo Clinic.

There have been quite a few publications, he noted, that have suggested surgery has no role in the management of Barrett’s. But there is in fact, he asserted, a subset of patients who would benefit from it.

“There’s tons of patients out there that have really bad reflux, and no one ever sends them to someone to be treated properly, and they’re just taking medications for years,” he said. Spector often has patients referred to him “because they’ve been taking omeprazole for the last 25 years, or however long, and now suddenly, they’ve heard on the internet or their doctor suddenly saw that these medications are problematic for long-term use.”

He stratifies reflux by how long the patient has had the condition, whether they regurgitate from it and if so, what symptoms does that cause, and how much medication do they need to take so that they don’t have symptoms. He also said my father is a prime example of someone who probably had reflux for many years and that he’d developed changes in the esophagus that eventually turned into cancer and killed him.

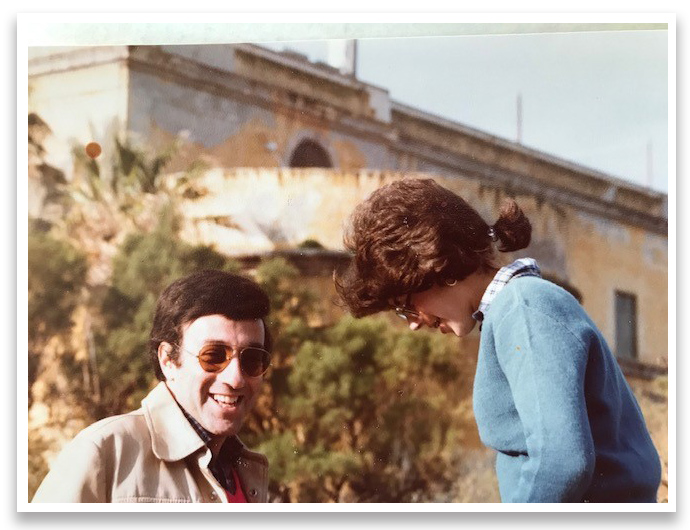

My father and me in happier times. When I look back at photos of my dad now, I wonder, was his body already deteriorating? What did his esophagus look like then?

Visual: Courtesy of the Chesler family

It’s likely that in the next decade or two, Spector said, “there will be a different way of us looking at this kind of stuff and part of the decision-making to roll towards an anti-reflux operation will be based on the fact that we know that Barrett’s can regress if we take away the offending problem, like the reflux.”

Scientists observe changes in the environment over decades, like sea levels rising from climate change. It’s a progression over time. It can be the same with cancer. A doctor friend of mine said, “It’s not like one day you don’t have cancer, and one day you do. It’s that one day you find out.” Something creepy slips inside you, like a vapor, and starts talking to your cells, whispering to them, turning them against you one by one.

When I look back at photos of my father now, I wonder, was his body already deteriorating when he was wearing that tuxedo at my brother’s wedding back in 1991? He had only 10 years left at that point. What did his esophagus look like then?

Suddenly, Spector asks me about my own condition.

“I was diagnosed with reflux when I was 29,” I said.

“Wow,” he said. Never a good word to hear from a doctor.

“I was getting those pains in my chest like a heart attack,” I said. Once I got diagnosed, I continued, my doctor “put me on the purple pill, and after a year, I said I’m not taking a fucking pill for the rest of my life. I’m just not.”

Spector then asked about my symptoms.

I get pain in my chest, I said, that “can actually radiate to my ear or my jaw, like toward my ear.”

It’s “distractingly uncomfortable,” I added.

“Do you ever have content go up into your throat — like you feel a bitter, burning feeling in your throat?” Spector replied.

Yes, I said.

“Bile-ish taste — Does that happen at night?”

“More in the morning,” I said. “I think my worst reflux could be in the middle of the night or in the morning.”

“You ever wake up at night coughing or choking?”

“No,” I said. But I told him “I often wake up with a sore throat.”

“You wake up with a sore throat?”

“I always think I’m going to get throat cancer, because I imagine that stuff is just coming into my throat,” I said.

“When is the last time you were at a gastroenterologist?”

It had been three years, but I was determined to go again soon.

Caren Chesler is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, Slate, Salon, and Popular Mechanics. She has a blog called The Dancing Egg, about having a baby at 47 through IVF.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I am late to the party here, but I needed to add my 2 cents. I’m 31 and a hypochondriac. I have been dealing with minor GERD in my early 20s to bad GERD for about ten years. Mainly LPR type of acid reflux. Constant clearing throat and cough.

I’ve been down the rabbit hole of trying everything from PPI to Algae tablets. It wasn’t until I came across a product called Valasta that changed my life. (I have nothing to do with the company, FYI) It turns out that most cancers and diseases stem from chronic inflammation. Most of the supplements/RXs out there don’t treat inflammation. There are only two supplements that are effective enough, and that is a liposomal form of Astaxanthin (Valasta is the best by miles) and SPM Active (Metagenics is my go-to). When taken in higher doses (completely safe), it will bring your hs-CRP levels below 3, which makes disease and cancer impossible to thrive. With GERD, my hs-CRP was 5.7 now; it is under 2. Most symptoms disappear unless I eat and drink bad things for a day or two.

Everyone needs to get a CRP & hs-CRP test. Then take both of those for at least 8 weeks and retest (I took 120mg of Valasta daily for 8 weeks).

What does acid do with our esophageal lining? Creates inflammation. Chronic inflammation for many years, then it turns into Barretts, then it goes from there. Nothing we are told to take stops inflammation like these two products.

What changed since the 70s? Added Sugars. It creates inflammation and cancer rates!

thanks for the nice article.I too lost my dad to esophageal adeno CA. He was already deemed stage 4, although I question that given that his liver spots, were likely hemartomas (benign liver cysts..which I also have…can be mistaken for metastatic disease). This was 15+yrs ago. Yes, all of my life my father had tums in his pocket and had stomach and indigestion. When he went in for a colonoscopy, he also claimed to have some heart burn..huge mass found at that time. He lived 18 months…chemo until platelets dropped then switched to Xeloda…followed by very late Radiation therapy…which just about killed him due to the burning pain..this was before palliative medicine…unfortunately he suffered …pain and could not swallow…looked like he was the size when he was a bar mitzvah boy…horrible to see…and he could not swallow..

Frustrated by his care and as a physician daughter, felt that I failed…I could not do anything…he closed up…did not communicate with my mom…definitely an ugly disease and would not wish this on any one. Awareness regarding chronic GERD is key…with surveillance, endoscopy, diet, etc. I too worry about genetic component. My dad was 75, fit, and enjoying retirement.

I and my student are doing research on esophageal cancer and trying to build a prediction model using machine learning.

Can anyone help like where can we find the data on the patients?

I am not sure that your comment is a completely accurate characterization of the lifetime risk of developing esophageal cancers. I understand you are trying to place the issue in perspective, but I’m not sure it is the right perspective. Let me explain that.

I have Barretts, was diagnosed more than 5 years ago, and had reflux for at least 10 years prior to diagnosis. Like the author, I feel as though I have a target painted on me…she because like her father she also has GERD. Me, because I have Barretts, and have read all this data, whipsawing between panic and denial with every conflicting or encouraging new study. Let me tell you right now that this is no way to live.

Heck, for all we know, based on studies conducted on adrenergic response, serum cortisol levels, and inflammatory disease, sheer Stress (physiological stress induced or mediated by psychogenic factors) itself could be the underlying factor causing people to have all these cancers and even cardiac events…so should we really let ourselves get all worked up about outcomes which we may ultimately not be able to affect no matter what preventative measures we take? BTW, I dislike articles that can give people false hopes – it seems that despite a few instances being observed, actually reversing the effect of Barrett’s is extremely unlikely. Removing metaplastic or neoplastic tissues can probably lower or even sometimes remove the risk, but even that, is not clear or certain.

Unfortunately, the statistics reported in “medical news” often suggest that 1% PER YEAR is the relative risk. Ie, from reading this stat, one would think that a 40-year-old with Barretts, has a 50% chance of developing esophageal cancer by the age of 90. This creates a lot of fear in the lay community because a 40 year old might see that and do this math in their heads and think well there it is, I’m gonna die from esophageal cancer with the same likelihood as winning on a black bet at the Roulette table. They don’t like these “odds” – suddenly a total toss-up “heads or tails” is now “Life or death.”

Now, in reality, that is only the mathematical implication and does not reflect the real world outcomes. The way the data are collected, the mathematical lifetime risk is clearly exaggerated when applied to the general population, because very few patients fit that model. The 1%/year data is based only on the population of people with Barrets. Typically that population is much older…in the 50s or beyond at diagnosis. In fact the average age is about 55. Interestingly men are about twice as likely as women to develop Barretts and white men are about twice as likely as other men of other races to get it (there’s some white and male privilege for ya).

So it is an absolute, but also additive risk – every year with Barretts is a fresh 1% chance of developing esophageal cancer. (If 1% were indeed the rate – which is not certain). That would apply no matter who you are and what age you are at, at the time. In other words, the annual risk isn’t greater in year 6 than in year 20, its always 1%. However, because its additive, the lifetime risk CAN be calculated by multiplying the rate by the number of years the risk has existed, but then that ignores that the average Barretts patient is already eligible to join AARP when diagnosed. So that’s part of the issue. At 55, the average man in the US only has less than 22 years left to live anyway. Thus, a 40 year old diagnosed with Barrett’s has more than double the total risk profile as a 60 year old and that is true regardless of dysplastic grading.

Based on studies in Denmark, the annual risk is actually far lower, somewhere between 2 and 3 tenths of one percent per year. Outliers like the 40 year old were probably excluded from this data, although I haven’t read it so I don’t know that for sure.

However, and this cannot be stressed enough ….that is a totally different patient population than exists in the US. As the author noted, Americans are fat. We are likely the most obese of all Westerners, due nearly entirely to our poor diets. The risk for an American might very well be 1%/year. We don’t really know. What we DO know is that obesity, and GERD and HH are all risk factors, and Americans score higher/highest amongst all developed nations on those factors. But does this risk score correlate well to observed rates of EC and mortality from EC? No, to both of those things.

What we can look at is life expectancy rates for Barrett’s patients, and if we do that we don’t find any significant deviations from the general population data, which is encouraging. This implies that despite having a greatly elevated risk of EC, overall mortality from all causes is basically the same. This means that whether you have Barrett’s or don’t, whether you are 40 or 70, assuming the annual risk is 1%, something else is 99 times more likely to cause your death – and at around the same age as everyone else in your cohort. As a white male, the likeliest population to become Barrett’s patients, we already live shorter lives than our better halves, by almost 5 years. (Note to the social justice brigade, we must get to work post haste on this “Gender Longevity Gap”. Surely President Warren will sound the clarion call?)

So that’s good news, I think, for people like the author, and myself, who both live with the fear of succumbing to something that could easily be imagined or reasoned to be our personal genetic destiny.

I’ve had problems with reflux all my adult life, never suspect that it might be also some dirty cancerous stuff. I’m after geting rd of throat cancer and reading all stuff over internet. for example in a book describing mostly common cancer types p Do I Have Cancer, I know that my symptoms were so obvious and I could deal with this much earlier with lower cost… Don’t underestimate signs, your body is giving to you!

When I was younger, I ate a typical junk food laden diet. During that time I also had severe acid reflux.

I changed my diet, eliminating most junk food and cured meats. My acid reflux stopped entirely with this change in diet.

Occasionally since then I have eaten cured meat. Every time I have done this, I experienced severe acid re-flux, hence proving in my case that acid re-flux is due entirely to diet considerations. I no longer ever eat cured meat and mostly eat a vegetable base diet.

Hi Virginia, sorry to hear your GERD diagnosis. DGL has helped me with acid reflux.

I’m sorry for your loss my farther also died of this terrible cancer. He too was only just 62. I also have reflux and as terrible as it sounds I’m terrified the same fate is awaiting me. My Dad was my absolute everything and still a year on its hurts as much as the day he passed.

Right on Mike benzodiazepines are a culprit!

Colin

Thank you for the post, it’s as interesting as scary.

What about LPR and cancer.

I am taking cimetidine which really helps.

Is there anything else I should be doing

I was diagnosed with Barrett’s Esophagus in January 2017. I went on an anti-inflammation, low-acid diet after reading “The Acid Watcher Diet” by Dr. Jonathan Aviv. I also started exercising more regularly every week.

The book was mentioned in Jane Brody’s column in the New York Times:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/20/well/pop-a-pill-for-heartburn-try-diet-and-exercise-instead.html

I had an Endoscopy in April 2018 and another in April 2019. I do not have Barrett’s Esophagus anymore, the cells are all normal.

I notice some of the “authorities” quoted in this article have significant conflicts of interest that just might color their perceptions. People reading the article need to be aware of that.

For example, the MD downplaying PPI risks is extensively funded by several PPI manufacturers.

For folks worrying about developing Esoph Cancerit pays to reread what was said early on: only a tiny percentage of folks even with Barretts go on to cancer. Far far less those with GERD.

Faint consolation of you are that person, bu you are likely NOT that person

PPIS are possibly the greatest invention in medicine. Only an idiot/nutjob thinks there is a better alternative, beyond born with a normal stomach.

Should really look into the health benefits of taking a hydrochloric supplement. It sounds counterintuitive; adding acid to a system that’s already producing too much.. ..but, if it’s understood that the microbiome is coming into play, as well, a desperate lunge-like effect whereby the body is over compensating for too low of acid by producing too much.. and continually getting worn out via this, it may make sense to see how adding HCl to the system could help not only adjust for this, but also readjust the microbiome that is having such an effect on the digestive pH to begin with.

I also had GERD, Barret’s, and esophageal cancer.

However, because my gastroenterologist knew I was at high risk, he did an upper endoscopy every 6 months. As a result, he caught my cancer at a very early stage and removed it surgically. I did not need chemo or radiation. That was 18 years ago, still cancer free.

So yes, see your gastroenterologist on a regular basis, and ask for regular endosopies.

Dear Caren,

I’m very sorry for your loss. I also lost my mother to untreated GERD, except in her case, she was aspirating stomach acid at night and inhaling stomach gases that over time caused the destruction of her lungs. She was misdiagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis because her pulmonologist couldn’t figure out a cause for the rampaging inflammation in her lungs. (My mother didn’t smoke, didn’t have a genetic history, didn’t have industrial exposure.) But my mother did have horrible reflux and a hiatal hernia. I am bitter to this day that her doctors did not treat the hernia and allowed her to suffer from a problem that could have been corrected, likely with life-saving results. Take care of yourself. D

I’m surprised there’s no mention in the article nor in the responses of the part played by use of benzodiazapines in all their flavors. Not long after starting to take half a Zanax before bed every night to induce sleep, I started to feel the effects of GERD and at one point lost my voice for a couple weeks since the acid had progressed up my esophagas to affect my larynx while sleeping. The benzos relax that sphincter separating the stomach from the esophagas allowing the acid to seep upward.

The severety of the voice problem went away over time, although I still occasionally have a rough voice, I suspect for this reason. I still habitually take a benzo analogue at night, etiozlam – available without prescription.

When investigating my voice problem (this occured nine or ten years ago) I discovered the relationship between benzo use and GERD. The relationship between benzos and GERD was known at the time so I’m surprised to not see it mentioned in this article with comments.

I am sorry for your loss, Caren. Thank you so much for writing this article. I suffer from GERD as well and have Barrett’s. This has been the most frustrating condition to manage especially as an adult and I am glad there are finally more in-depth discussions happening around acid reflux. I had been meaning to make an appointment with my gastro doctor and after reading your article this morning, I did just that.

This is a very good article. I lost my husband 5 months ago due to esophageal cancer. It is a brutal disease with a very high rate of mortality. He had GERD when I married him. He progressed from Tums to Rolaids to Zantac to omeprozole over 45 years. No one told him he needed an endoscopy until he couldn’t swallow.

I’m very upset with the medical system and I am a nurse.

BAKING SODA IN WATER

this will get rid of reflux completely and make you bupr like a trooper, no PPI bs and no side effects – it’s that simple

GMO foods and Microwave Ovens!!!

I began to experience bad symptoms with a sore throat ( but no cold) and a constant hacking dry cough

This was almost 23 years ago. My gastric doc diagnosed me with early stages of Barrett’s and suggested the ablation. A few days after surgery, I had to go back in because food was getting stuck in my throat. My recollection is they used done kind of balloon to open up the throat. Fast forward 23 years, no signs of recurring Barrett’s but I have been on PPIs ever since. They may have had an effect on my hip fracturing while I was awaiting my date for hip replacement surgery.

We talked about the other surgeries but they were a little too radical for me. I keep hoping there will be another less radical cure. For now, I live with the status quo

Thank you for your very interesting and thoroughly researched article. I have had reflux for 9 years. Almost immediately after my 5th c-section I got SIBO and two years later reflux. I do believe they are both the result of the 5 pelvic surgeries I had. I have been going to acupuncture every week for the last 7 years. It will never cure the reflux, but it appeases it. Without acupuncture my reflux would be out of control. I ordered some of the Kfibre. Hoping it helps!

I have acid reflux and I have tried everything that’s out there and nothing help tomorrow I will call my doctor to schedule an appointment for an endoscopy. My sister passed six months ago from cancer of the esophagus.

The last part, about the bitter taste at middle night and morning, really got my interest. I have been trying for a decade to figure out why the bitter taste. Even though I don’t have frequent heartburn issues I have gone after this issue as though it were GERD or LPR. PPI’s, Gaviscon, wedge pillow, and you name it. It’s just a nasty but not sour taste, made worse if I do a mouthwash. My gastroenterologist just says if using a PPI doesn’t improve it then it is out of his realm, without suggesting who’s realm might help me. He was not interested in testing further and was dismissive of any question about the sphincter. I have excellent dental hygiene and the dentist sees no erosion of oral tissue. The article makes me want to revisit this issue but I’m not sure how to approach.

Please accept our sincere condolences on the passing of your father. Thank you so much for shedding light on this devastating cancer. I, too, lost my father to esophageal cancer. It will be 21 years since he passed on Father’s Day in 1998. My family and I started The Salgi Esophageal Cancer Research Foundation in his memory and our mission is to raise awareness, encourage early detection and to fund research of esophageal cancer. We are successfully achieving all three components of our mission and honored to share that in November, 2018, we awarded research funding for the second time since the charity was founded in 2011. Our hearts go out to everyone who has been impacted by esophageal cancer. There is a dire need for awareness of risk factors, symptoms and research for early detection, improved treatment options and underlying causes of esophageal cancer. Thank you again for sharing your father’s story.

I was diagnosed with GERD at around 23 (after years of being told my inability to swallow was because of anxiety, of course, as a woman). The doctors weren’t quite sure whether or not to put me on a PPI then, and I tried a few that didn’t seem to make much difference. Fast forward a few years, and at 28 I’ve now had four dilations due to narrowing of the esophagus and now take a PPI daily. My most recent doctor said I had the worst case he had ever seen for someone my age, so prospects aren’t great. The trouble with GERD, as this article kind of suggests, is that really aren’t any clear steps to follow. Should I be taking a PPI daily forever or not? My mother and brother both have GERD as well and take PPIs, and have had dilations, but now my mom wants to get off of them because of the side effects. After the dilations the chest pain/food getting stuck stopped for me, which is a mercy. I’ve had a lot of teeth issues, wearing away of the enamel, etc. and every morning I often cough up gunk that seems like solidified acid. Sigh.

From another science journalist, thanks very much for writing this story for everyone who suffers from this.

Excellent article. My husband suffered from acid-reflux from the time he was 16. He developed Barrett’s Esophagus in his 40’s despite taking PPI’s. Fast forward to 2015 when I came across an article in our local business journal about a physician who helped develop the magnetic ring that goes around the esophagus to help the sphincter muscle close (and lived in our community). My husband went through rigorous tests to see if the magnetic ring would work for him. As it turned out his esophageal sphincter was too week to benefit from the magnetic ring.

But, he was a candidate for the Nissen Fundoplication surgery which he did have. The operation was very successful, and he has not had to take any PPI’s or antacids since.

My late husband died at age 57 from esophageal adenocarcinoma, after many years of GERD and taking all sorts of PPIs. Was never diagnosed with Barrett’s; main symptom was trouble swallowing and after that, we were off to the races: surgery, radiation, chemo. 18 months from diagnosis to death. His surgeon–chief thoracic surgeon at Georgetown U–said she believed there must be environmental contributors and that she was embarking on that avenue of research. I never followed up with her. Too painful, even for me, as a journalist, to revisit that whole thing. Thanks for your work.

Who was his surgeon?

I’m 56 years old…and of Jewish extraction. I mention this, as, in looking at photos of your father in his youth, his facial features are so similar to mine and my father’s at that age that we could almost be related. As well, my own DNA test indicates 23% of Eastern European Jewish extract. So, I must wonder if excess stomach acid has a heavy genetic component as part of its cause.

Over the last few years, I had increasing issues with occasional acid reflux…no actual diagnosis…but occasional bouts necessitating antacids and the occassional Zantac–and, yes, some attacks were very painful. I also became incredibly intolerant of red wine. It felt like it was setting my gut on fire and eventually associated with a sore throat that constantly felt like I had just burned it with hot scalding coffee–it was unrelenting. Unfortunately for me, a red wine lover, who even made his own, stopping red wine was the only thing that truly alleviated this. I can still drink 1-2 beers/day and tolerate white wine. I believe, without any actual medical diagnosis, that maybe I actually suffer from histamine intolerance, something that I believe Zantac can also address. With abstaining from red wine, my acid reflux is all but gone now; even though what I may be experiencing is not true GERD, this article, for me, is cautionary. Thanks again for publishing.

“When I’m having a bout of reflux, I drink apple cider vinegar and sleep on a foam wedge pillow to keep it at bay. I’m not sure why the vinegar works for me — the science is lacking ”

The apple cider vinegar seems to induce the valve to close, and that keeps the acid in the stomach.

I am a 36yr old male recently diagnosed with Barret’s. I was told that I needed to go on PPIs for life. When I looked into the what PPIs long-term effects were, and the fact that I young, I did not want to go on PPIs, so I looked into other ways to treat my condition.

I found a website: http://fixyourgut.com where I worked with John to eliminate my reflux, which I did. I am now reflux free without the aid of PPIs or any other drug. I encourage folks to seek alternative methods to elimination of reflux through the use of supplementation and changing of your diet. I do not know if my Barret’s has gone away, but I will check later this year. Good luck everyone!

Adam, can you say what you did to reduce, even eliminate, your reflux?

How do you know you are now free of reflux? Though it was not covered in the article, many people have silent reflux, including silent reflux severe to cause Barrett’s and cancer. It is interesting that you would trust some dude from a website over your doctor, especially, as stated in the article, that the supposed side effects from PPIs are far from established as fact. I am confused that the fact that you are so young is an argument against PPIs. Having Barrett’s when you are so young is what should scare you.

Hi and thank you for sharing this story. I’m sorry about you losing your Dad to Esophageal Cancer. Many don’t realize that it can arise from chronic untreated/undiagnosed GERD/Reflux. As April

marks Esophageal Cancer Awareness month (the ribbon color is periwinkle), so sharing your story helps towards raising awareness. There are procedures available to help resolve GERD/Reflux by fixing the anatomical issue rather than masking symptoms with PPIs and medications. For example: Traditional fundoplication surgery ie: Nissen/Lap Nissen, which involves cutting the anatomy in the abdominal area to fix the spinster area/valve issue; and/or a Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication (TIF) surgery that is done without incisions, through the patient’s mouth and from within the stomach under full visualization of an endoscope. GERDHelp.com is a consumer education website with a lot of information for those suffering from GERD/Reflux. The bottom line is that if you’re suffering from chronic GERD/Reflux, schedule a visit to talk to your Primary Care or GI Doctor about it. They can determine next steps re: potential treatment options. Please don’t ignore symptoms or assume they are harmless. Take the next step and get a proper evaluation. It’s better to be safe now than possibly sorry later for having put it off. Today there are several effective and SAFE treatment options to help resolve GERD at the root cause of the disorder. Ask your Doctor for help.

“safe” is a relative term. I have a phamacist friend who says he would never have an abdominal surgery, because he has seen too many bad outcomes. My own experience supports his fears.

I had a Nissen fundoplication, but it somehow came undone.

So a year later, they opened me up to redo the surgery, but 3 days later my stomach ruptured.

I was in intensive care for over a month, on a respirator the whole time, and in the hospital for 67 days. And that was over the holidays, no less! Beforre Thanksgiving till late January.

Then 3 years later I got the cancer anyhow, so they removed my esophagus and most of my stomach.

But that was 18 years ago, and I am still cancer free.

I was diagnosed with GERD at the age of 16, after having terrible sore throats and a cough for nearly 2 years. That was 33 years ago and this article worries me. Thanks for shedding some light on the issue.