Building Diversity in Science, One Interaction at a Time

To get to her Thursday morning biology class at San Francisco State University, Imani Robinson would often hop off the bus and take a shortcut through the hallway of a neighboring building. The hall was drab and institutional, its beige walls lined with award plaques and headshots of engineering faculty. The framed grid of faces — largely male, mostly white or Asian — caught the attention of Robinson, an African-American student. But what really got to her were what she described as repeated, suspicious stares from professors watching a young woman with dreadlocks pass through their halls. “They’d do double-takes, looking to make sure I had a backpack,” said Robinson, who graduated in June with a bachelor’s degree in biology. “They would stare at me like I’m in the wrong place, like I wasn’t supposed to be there.”

However brief or inadvertent, incidents like this can have outsized effects on racial minorities and other marginalized groups who routinely experience them. In science and math, such indignities can create a culture that shakes confidence and hurts performance, making underrepresented students feel they don’t belong — and many quietly leave.

Hispanics, African-Americans, and Native Americans make up about a third of the United States population, yet they occupy just 3 to 4 percent of basic science professor positions at American medical schools — a minor increase over their 2 percent representation as measured 50 years ago. These gaps persist despite recognition by the National Institutes of Health that diverse groups produce better ideas and discoveries. Research led by minority scientists, for example, has shown that race and ethnicity can impact disease severity and drug responses for asthma, diabetes, and other medical conditions.

“It’s been proven over and over again that diverse groups perform better,” said Alison Gammie, director of the NIH’s Division of Training, Workforce Development, and Diversity. “People work on things they’re passionate about and that affect the people they care about,” she said, so science benefits when “we have people from all kinds of backgrounds, races, ethnicities, experiences, coming to do the problem solving.”

Diversifying the biomedical research workforce is especially critical given the push toward “precision medicine,” which tailors disease treatments to individuals. Yet clinical studies still enroll mostly white patients. And when researchers tracked students’ progression from high school graduate to medical school faculty to see where in the biomedical career pathway underrepresented minorities were turning away from the field, they found two critical junctures. One was the transition from postdoctoral training to tenure-track faculty. The other was during undergraduate education.

In many cases, a nagging sense that they weren’t welcome — or worse, that they might somehow fulfill or validate entrenched, negative stereotypes about their race or ethnicity — helped to derail their careers in science.

Over the last four years, the NIH has issued more than $180 million in grants to 10 colleges and universities to test strategies aimed at keeping students of color from falling through the cracks in science and math programs. Called the Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity, or “Build” initiative, the program seeks to broaden the pool of students who choose biomedical careers by addressing what many consider the crux of the problem: non-inclusive culture.

Toward that end, faculty and researchers at SF State — itself a historical touchstone in the fight for racial and gender inclusion — are now busy trying to identify and track those discrete moments and brief interactions that can, over time, cause a budding science career to go sideways for minority students. Along the way, they’re using innovative teaching techniques and modern data collection tools to test the depths (and shallows) of a litany of psycho-social concepts — “stereotype threats,” “microaggressions,” and even “microaffirmations” — to get a handle on how faculty, staff, and students can make science and technology fields more welcoming and inclusive.

“If we create inclusive and affirming environments, we will change who gets included in science and how it’s practiced,” said biology professor and leader of SF State’s Build efforts, Leticia Márquez-Magaña, in a video highlighting the project’s objectives.

Similar efforts are underway at other institutions, including California State University, Northridge, which is using its Build funding to develop a curriculum that helps science students recognize historical and institutional roots of educational inequality and empowers them to navigate these barriers. The Build program at the University of Fairbanks similarly aims to engage native Alaskan students with a One Health paradigm focusing on the ways environmental, animal, and human health are interconnected.

“What’s really exciting about Build is that it’s taking a scientific approach,” said the NIH’s Gammie. “The hope is that we will be able to get at why [the training and mentoring interventions] work. Not whether they work, but why they work.” The goal is institutional impact, she said. “A research-infused culture where students are pulled into the majors and we continue to sustain their interest in getting a STEM degree and moving into a research-related path.”

The fight for inclusion at SF State reaches back decades. In November 1968, students stormed the streets with picket signs and bullhorns, demanding more faculty of color and a revamped curriculum that includes the history and culture of ethnic minorities. “The university shut down for five to six months,” said Márquez-Magaña, who came to SF State in 1994 as the science department’s first Latina faculty hire. The strike made national news, and it gave rise not just to the university’s own College of Ethnic Studies, but to similar programs at hundreds of other U.S. campuses.

Fifty years later, Márquez-Magaña sees the Build program as the latest chapter in the legacy of educational inclusion at the school — and it’s a struggle with which she is familiar. From playground taunting to being told to settle for community college, Márquez-Magaña recalls a childhood filled with overt and implied discouragement. Undeterred, she earned a bachelor’s degree in biology at Stanford University, and continued straight on to her master’s. “I wanted to make sure that if I was coming out with a biology degree from Stanford, that I could represent well,” she said. “That was my biggest motivation.” She later earned a doctorate in biochemistry at the University of California, Berkeley.

Today, SF State is a mostly minority campus, with many students who are the first in their families to go to college. But to these first-generation students in particular, science classrooms can still have an exclusionary feel. Khanh Tran, the youngest son of Vietnamese immigrants, is a biology and Asian-American studies major at the school. Several years ago, while taking an ethnic studies class, he noticed how students were invited to share their own experiences — to talk about “what do you know, and what can you bring to the classroom,” Tran said. Science lectures, in contrast — often presided over by white men stressing Euro-centric values like individual discovery and scientific competition — took little interest in students’ culturally divergent approaches to research and empiricism. Many students came from ethnic backgrounds valuing interpersonal connection and cooperation, for example, but felt that there was no place for this in science classrooms. Others, Tran recalled, felt that success required leaving their humanity and cultural identity at the door.

“When I stepped into the science building,” Tran said, “I felt like I had to zip on a white persona.”

In 2016, he shared these thoughts with Imani Davis, an African-American classmate who was also taking biology and ethnic studies classes. In addition, both served as facilitators in small peer-led classes, called supplemental instruction, aimed at supporting students in large-lecture STEM — science, technology, engineering, and math — courses. The two students wondered what it would be like to incorporate the personal reflection and sharing components of ethnic studies classes into a science classroom. Could this small change encourage first-generation students to stay in STEM and get their degrees?

That year, with help from SF State chemistry professor Alegra Eroy-Reveles, Tran and Davis put these ideas to the test. Each week at the start of their supplemental instruction period, rather than opening textbooks or diving straight into a problem set, they handed out journals and asked students to spend 5 to 10 minutes answering a question about personal experiences and motivations. How are your family’s values helping you navigate college? What are your goals, and how can this class help you achieve them? Recall a moment that made you want to pursue a STEM major. How did you feel?

At the end of one such class, Tran said a student came and talked with him about the journaling. The young man was in tears, Tran recalled, saying that he felt stuck in a rut, depressed. “He was like, ‘Thank you so much,’” Tran said. “No one ever asked me about my family or background.’”

The trial run earned local press coverage and earlier this spring, the team secured Build funding to expand the journaling practice to 16 biology, chemistry, physics, and math classrooms. The project has since grown to involve about 2,000 STEM students at SF State and a neighboring campus, the University of San Francisco.

“Going to college is scary when you feel you don’t belong,” Tran said. “If I can ask them to think about their own story, that’s enough.”

During his first semester at SF State in fall 2015, Sergio Ramirez was floundering. “I couldn’t relate to a lot of people,” he recalled. “In STEM … you have to leave your feelings and emotions and history at the door so you can assimilate and progress.”

Ramirez said he was one of very few students of color in a white-dominated environmental science class. Each day the professor asked students to give examples of ways to be more eco-friendly — taking shorter showers, walking to the grocery store instead of driving, or turning off the air conditioner when you’re not home. “Well, I grew up broke so I take five minute showers and I don’t have a car … we never had central A/C,” Ramirez said. “By the sixth day, I ran out of things to say.”

Realizing the cultural and socioeconomic gap between him and his classmates, Ramirez says he hardly spoke during class discussions. “I’d be like, ‘no, they would say that’s silly’… even if I knew the right answer or thought I had a good idea,” he said. Other students seemed more articulate. “It really sounded good, the way they were speaking, the words they were saying,” he recalled. “They had a leg up.”

This sort of self-doubt saps mental energy and hurts performance — particularly for students from underrepresented groups who already struggle with feeling they don’t belong. Usually the psychological strain arises from the fear of confirming a negative perception about one’s social group. In academic circles, students who identify as black, Latino or Native American often contend with nagging beliefs that they won’t succeed in math and science.

In a pivotal 1997 paper, Claude Steele, a social psychologist at Stanford University, coined a term for these predicaments: stereotype threat. According to Steele, what makes such circumstances tricky is that from the outside, “the situations of a boy and a girl in a math classroom, or of a black student and a white student in any classroom, are essentially the same. The teacher is the same; the textbooks are the same; and in better classrooms, these students are treated the same.”

And yet minority students like Ramirez experience the classroom very differently than majority students — and often suffer under the radar. “At the back of your mind, unconsciously, you’re thinking, ‘Gosh, am I supposed to be here?’” Márquez-Magaña said. “Your stress response is activated. Your cortisol levels go up. Your working memory is being tasked with thinking about this stuff consciously or unconsciously, instead of just performing.”

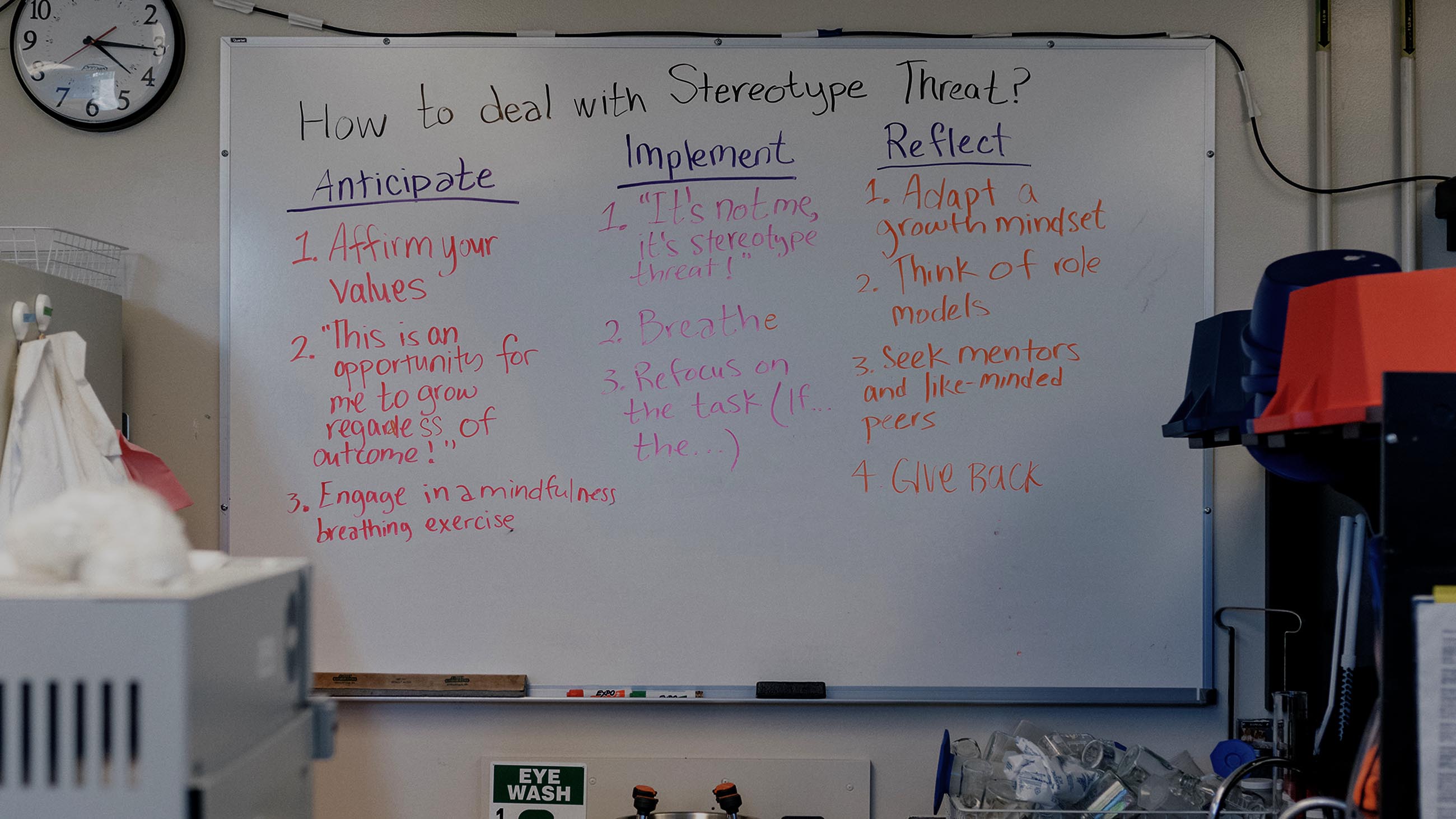

Márquez-Magaña has worked with a team of researchers led by SF State psychologist Avi Ben-Zeev to design a short web-based tutorial, funded by Build, which teaches students about stereotype threat and encourages them to draw upon lived experiences to cope in these situations. Last year, the team published a study showing the program helped underrepresented minorities perform better at school and build resilience to future threats.

Still, it’s not just about fixing the student, Márquez-Magaña said. “It’s more about fixing the institution, the faculty, the peer mentors.” Toward that end, Márquez-Magaña and her colleagues are leading workshops with new faculty and student facilitators at the school, as well as with staff at other Bay Area campuses. Ifeyinwa Asiodu, an assistant professor in the School of Nursing at the University of California, San Francisco, learned about stereotype threat at a workshop led by Márquez-Magaña last summer. “It was the first time I’d heard the term,” Asiodu said. “I was completely taken aback.”

Growing up in southern California, Asiodu was the only black girl in her fifth and sixth grade classes. Continuing through high school, college, nursing training, and graduate school, “I’ve gone almost my entire academic career in terms of being an n of one… or one of very few,” said Asiodu. “I don’t know that everyone understands, or has experienced that phenomenon, of being in a space where there are no other clinicians or researchers or just anyone who looks like you or has similar experiences.”

She’d heard of imposter syndrome — the psychological pattern where a person doubts his or her achievements and fears being exposed as a fraud. But stereotype threat was different. “The focus wasn’t just on the individual person, it really highlighted the system and institution we are in and their role in making individuals feel a certain way,” Asiodu said. “It was refreshing to hear the information and realize that folks had identified this as a problem.”

Márquez-Magaña, too, felt validated when she learned psychologists had a term for something she had quietly endured for much of her academic life. Struggling through introductory biology and chemistry courses as a Stanford undergraduate in the 1980s, she said she nearly switched her major to Chicano studies. But when she earned the top score on a molecular biology exam during junior year, Márquez-Magaña had a striking realization: “I was like, oh my gosh, I can be good,” she said. “It wasn’t that I was not smart. It was that I was underprepared.”

Still, there was a problem. “I couldn’t get into research labs,” Márquez-Magaña said. “The white and Asian men always seemed to get the research experiences, and I assumed it was because they were better prepared.” She figured it had something to do with connections they had and she didn’t — or that there was just “something deficient in me.”

Looking back, she suspects it could have been that “their assets were seen more clearly than mine … as a first-generation short brown woman.” And it’s not hard to see how these sorts of unconscious prejudices — called implicit biases — can arise. Márquez-Magaña recalled having a heated exchange with a white male classmate during a study section in her college dorm. At one point, she said, the other student told the class that the only Latinas he had ever seen or talked with were “the ones who worked for us, cleaning the house.”

It was what many researchers over the last decade would call a microaggression — a term coined in the 1970s by African-American psychiatrist Chester Pierce at Harvard University. It’s meant to capture the more nebulous forms of bigotry that, while often unintentional, can make some people uneasy. Some psychologists argue that microaggressions are poorly defined and thus the evidence for their harm is inconclusive — though the subdisciplines of psychology are replete with research into overlapping concepts like “implicit bias,” “modern prejudice,” “covert racism,” or “ambiguous threat.”

Whatever the label, Márquez-Magaña said the dorm conversation was an aha moment for her. “That guy’s perception about Latinos was colored by the fact that the only ones he had run into were in the service industry,” she said, “and so it was very hard for him to accept the rest of us.”

More recently, some researchers have begun focusing on a contrary concept — microaffirmations. Mary Rowe, an economist and former ombudsperson at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, describes these as “apparently small acts, which are often ephemeral and hard to see, events that are public and private, often unconscious but very effective, which occur wherever people wish to help others to succeed.”

Neuroscience research suggests it could be more effective to train people to deliver microaffirmations than to avoid microaggressions. Microaggressions are like the proverbial elephant in the room. “If you tell someone, don’t do a microaggression, they do a microaggression,” said Márquez-Magaña. Instead, it may be easier to encourage people to seek opportunities to affirm. Another challenge with focusing on microaggressions is that discussions and trainings on this topic can leave some whites, Asians, and other overrepresented groups feeling they’re being targeted as perpetrators.

Last year, Márquez-Magaña teamed up with SF State psychologist Charlotte Tate and computer scientist Ilmi Yoon to create a cell phone app for logging both microaggressions and microaffirmations. Funded by Build and inspired by a similar mobile app built by researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz for tracking microaggressions, the SF State team started beta-testing its app in April.

For each incident, the app gives users space to jot down a brief description of what happened, noting the time and place. Using checkbox menus, they can indicate if the incident involved race, gender, sexual orientation, or other factors. And there are slide-scale surveys for users to indicate to what they extent they felt angry, sad, uplifted, or a range of other emotions after the incident.

Robinson was one of the first beta-testers, and the suspicious glances from engineering professors were one of the first microaggressions she submitted on the app.

She’s also logged microaffirmations — such as the time her ancient Roman literature professor compared poetry to hip-hop music. She related what we were studying to “my kind of music,” Robinson said. It was a small gesture, but it helped create an atmosphere where Robinson felt comfortable in her own skin. “I could open my mouth and share my thoughts and emotions without being regarded as ‘the black person’ in the classroom,” she said.

Márquez-Magaña hopes these and other logged incidents will give a snapshot of campus culture that will help the team test other strategies for supporting underrepresented minorities in biomedicine. Some of the microaffirmations have been shared anonymously at professional development trainings to help faculty see the power of these small, purposeful gestures. Whereas the stereotype-threat training focuses on “the disease,” Márquez-Magaña said, the microaffirmations are “a solution, an antidote.”

Ultimately, the goal is to create learning spaces that are affirming and inclusive of all populations — particularly those that have been historically excluded.

“By fixing it for them,” Márquez-Magaña said, “you fix it for everyone.”

Esther Landhuis is a California-based science journalist who writes about biomedicine and STEM diversity for teens, Nobel laureates, and everyone in between. Her stories have appeared in Scientific American, NPR, Nature, Quanta, and Science News for Students, among other places.