In the Delta Smelt, Warnings of Conservation Gone Wrong

Peter Moyle, an eminent authority on the ecology and conservation of California’s fishes, stands on the narrow deck of a survey boat and gazes out over the sloughs of Suisun Marsh. The tall, tubular stems of tule reeds bend in the wind as a flock of pelicans soars past, their white wings edged in black. It’s an idyllic scene that hints at an earlier time, back before the Gold Rush, when undisturbed creeks and tidal marsh covered the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

In the delta, two of California’s greatest rivers meet and mingle with the ebb and flow of tides from San Francisco Bay, forming the largest estuary on the Pacific coast of the Americas. Moyle knows well how this place has changed. The delta’s once wild labyrinth of meandering rivulets and floating tule islands have been replaced by a network of levees that wall off agricultural fields, towns, and remnants of wildlife habitat from the tides. A legion of invasive species now course through the reshaped channels. The many tributaries that run down from the Sierras to feed the delta have been dammed and diverted to provide water for cities and farms — a maze of infrastructure and engineering that has pushed several species of native fish into steep decline.

The creature Moyle has studied the longest and knows most intimately is the Delta smelt, now on the brink of extinction.

Moyle was a young fishery ecologist, newly hired at the University of California, Davis, when he first encountered the finger-length, translucent fish in 1972. He chose to study the Delta smelt because it was abundant but little understood. During the 1980s, he documented a crash in the smelt population, and by 1993, the fish was listed as “threatened” under both the federal and California endangered species acts. As head of a team responsible for charting a course toward the smelt’s recovery, Moyle suggested a radical solution: Conservation in the delta, he said, should focus not just on the smelt, but on an array of native fish with different life histories and habitat needs, including steelhead and sturgeon. All of their populations were dwindling as humans reshaped the ecosystem, but only the smelt and winter-run Chinook salmon were officially listed as threatened.

Moyle’s idea didn’t take hold and government efforts instead followed the letter of the federal Endangered Species Act, focusing only on the smelt. Years of intense study and controversy followed, including a series of court cases over allocating water for smelt habitat. The species continued to dwindle. In 2009, California officials changed the smelt’s status in their listing from threatened to endangered, and by then, another run of Chinook salmon, a run of steelhead, and the region’s population of green sturgeon had all joined the smelt on the federal endangered species list.

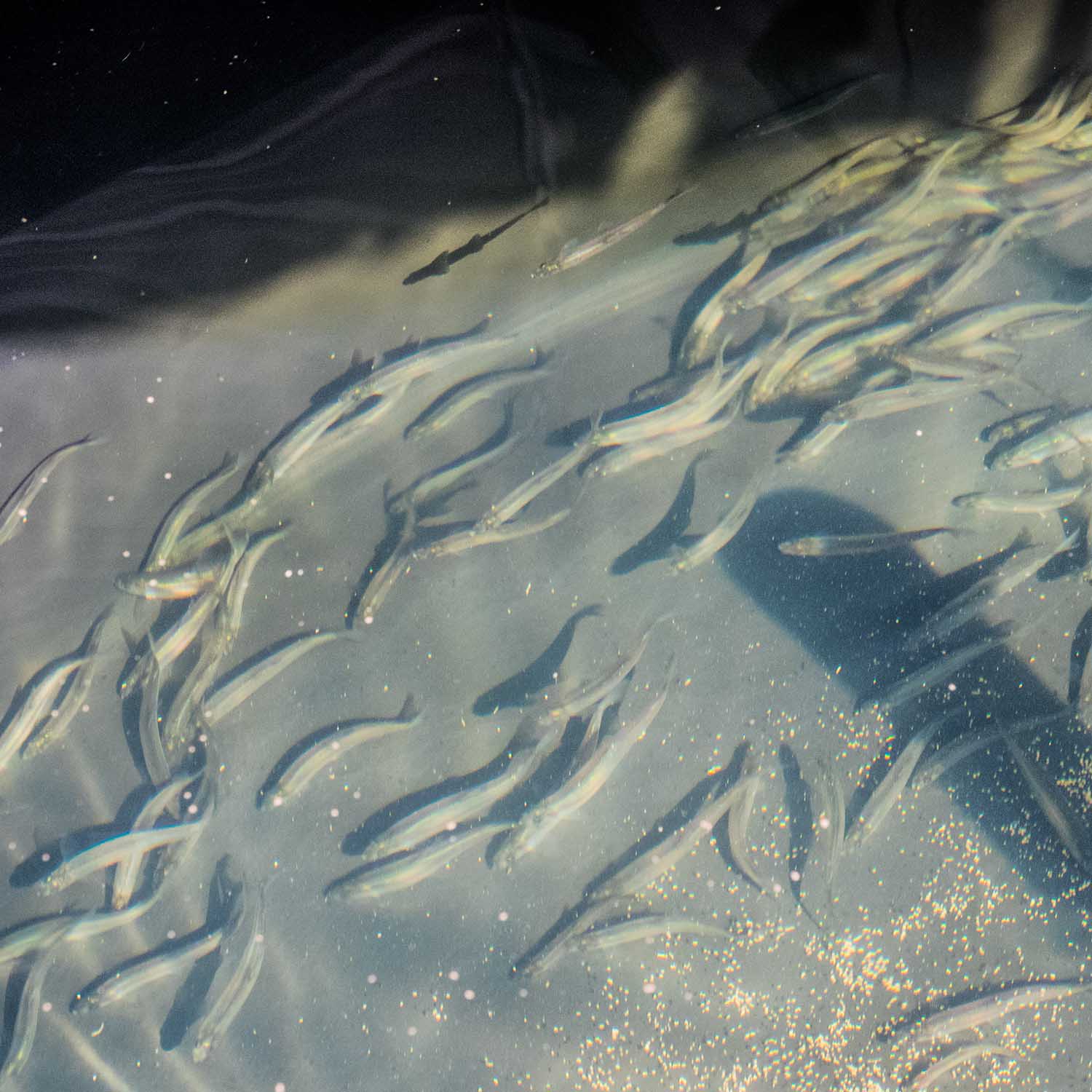

In the spring of 2015, a survey of wild spawning smelt found only six fish. Today, an estimated 48,000 survive in the wild — a small remnant of pre-crash populations. About the same number live in culture facilities created to prevent the smelt’s extinction. To some Californians, that’s of little consequence, and they regard efforts to protect remaining smelt as an exemplar of absurd environmental overreach. Why should an obscure fish, rarely seen by anyone but researchers, impair the flow of precious delta water to the thirsty farms and cities of Southern California?

But many ecologists, Moyle among them, consider the smelt’s rapid disappearance the signature of both an ecosystem, and a conservation strategy, in crisis. Moyle’s devotion to the smelt, and to the delta, appear unshakeable. But he remains pragmatic about the future. The delta, after all, has been transformed: Vast marshlands have been destroyed, water flows have been diverted to support human uses, and alien species now dominate the ecosystem.

That’s the context in which the smelt and other native species must now compete to survive — and it’s the reality that conservationists must face. As it now stands, the Delta smelt has high odds of becoming the first fish to go extinct in the wild while under the protection of the federal Endangered Species Act. Others might well follow unless new strategies take hold.

“If we’re going to save the Delta smelt,” says Moyle, “it has to be in the context of a totally different ecosystem than the one it evolved in.”

Ecosystems have always changed, of course — in response to the shifting of tectonic plates, or the advance and retreat of glaciers. The delta and all the species endemic to it evolved after the end of the last ice age, beginning about 6,000 years ago. The difference in modern times is that the changes happen much faster than ever before, as humanity reshapes landscapes and waterways, accelerates global warming, and carries species between continents and oceans.

These actions can create novel ecosystems — assemblages of species that have never before coexisted, in landscapes transformed by human actions.

Scientists began discussing the idea of the “novel ecosystem” in the early 2000s, around the same time the term “Anthropocene” became popular. Richard Hobbs, an ecologist at the University of Western Australia, has written extensively about the concept, and his work has influenced Moyle’s thinking about the delta.

Managing endangered native species in novel ecosystems can be confounding. Hobbs points to the case of the Carnaby’s black cockatoo, an iconic parrot in Western Australia, which has suffered the loss of much of its native habitat. Once the cockatoo fed on the seeds of native banksia plants and eucalyptus trees. Now, the surviving birds feed heavily on pine seeds in plantations of introduced trees. As the human population grows, demand for water increases. A government task force found that pine plantations prevent recharge of dwindling groundwater and state officials decided the plantations should be harvested without replacement. Yet in the absence of native forests, the pine plantations serve as critical habitat for the cockatoo.

A soggier example comes from Florida, where the snail kite, a native hawk, has suffered from human engineering of flows that once fed a vast maze of wetlands. The kite evolved to prey almost exclusively on the Florida apple snail, Pomacea paludosa. The kite population dropped dramatically in the late 1990s and early 2000s. At about the same time, an exotic apple snail from South America, Pomacea maculata, was introduced and began to invade Florida lakes and wetlands. The non-native snail, which is hardier and more prolific than the native species, has come to dominate many Florida habitats — and has proven to be a lifeline for the snail kite. The number of nests, body weight of fledgling kites, and survival rates of young birds have all increased in habitats dense with alien snails. In recent years, most of the breeding snail kites have relocated to lakes in northern Florida where the new snails are most abundant, and the kite population has grown significantly.

The invasive apple snail can be destructive, devouring all sorts of vegetation. It has been known to denude some wetlands, and alter the plant community in others. It can degrade habitat used by largemouth bass, a fish native to Florida and cherished by anglers. Some wildlife managers see good reason to slow or halt the snail invasion — if they can — while those who focus on protecting the snail kite see the invasion as a boon. What’s best for the snail kite may not be best for the whole ecosystem — a complex web of relationships even absent introduced species.

The framers of the Endangered Species Act never envisioned such tangles of native and invasive species. The legislation passed in 1973 with little debate, and discussion of the bill focused on charismatic creatures like the gray wolf, bald eagle, and grizzly bear. No one voted against the Senate bill, and only four members of the House voted no. It seems likely that few understood the potential power of the ESA to conflict with water projects and other major developments — a reality that played out a few years later, when a small endangered fish halted construction of the Tellico Dam in Tennessee.

Visuals: Tracy Brooks/Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources; Tim Taylor/Flickr/CC; Gregory Smith/Flickr/CC

The ESA’s focus on single species was a natural progression from previous wildlife law, dating back to royal trusteeships that controlled game hunting in Europe. Researchers estimate that the law has prevented the extinction of more than 200 species — including dramatic recoveries of the bald eagle, the peregrine falcon, and the gray wolf in parts of the West. But most often, the ESA functions as a sort of emergency room for life forms on the brink, offering protection only after species have suffered drastic loss of population numbers and habitat. Listed species in decline far outnumber those whose populations are growing.

In an ideal world, the law would be updated to incorporate a modern understanding of the need to protect and manage whole ecosystems. “You really need to change the ESA, but no one dares to do it,” says Moyle. “They’re afraid to open up that Pandora’s box, so to speak. [The law] will get gutted and not be good for anything.”

“We’ve not had a good national conversation about conservation goals since the 70s, and we’re overdue for one,” says Holly Doremus, an expert on environmental law at the University of California-Berkeley. “Unfortunately our political institutions don’t seem like they’re necessarily capable of that right now.”

A key problem with the ESA as written, explains Doremus, is that it does not focus on ways to improve or protect the wider environments in which listed species cling to existence. The bar was set far lower: To stop people from carelessly causing extinction in the course of everyday manufacturing, building, farming, and hunting. Protection of whole ecosystems was not built into the law, and its aspirations were based on the past: to hold on to all the species that populated the United States before European settlement.

The struggle to protect a threatened or endangered species in a novel ecosystem is a new frontier.

People have to recognize that they “can’t freeze nature at any point,” says Doremus. “For many systems, we can’t have something that looks like the world of 1500. As we’re forced away from that grounding, we need to articulate what our values are and what we’re trying to achieve.”

Teejay O’Rear, supervisor of Moyle’s lab, captains the survey boat as it skims through Suisun Marsh, at the delta’s western edge. He passes a hand through his long gray sideburns as he announces the vessel’s rules: Grab something solid when he goes fast, don’t knock over the fishing rods, and absolutely no carp-hating. The common carp, an introduced species that thrives in the delta, is disdained by most local fishermen. O’Rear admires carp as strong, resourceful beasts, long established in the ecosystem.

At Denverton Slough, Moyle and a student deploy a trawl net, which captures organisms from the entire water column — about 3 feet deep at this stage of the tide. After towing the net for a few minutes, they haul it in, emptying its contents into a wide shallow bucket. The creatures that squirm together in the bucket evolved all over the world: American shad and striped bass, native to the East Coast of the U.S.; the translucent Siberian prawn, from East Asia; the common carp, deliberately introduced to California streams in the late 1800s by European immigrants who longed to catch and eat the fish they’d dined on at home; the shimofuri goby from Japan and China, a chubby-looking fish that seems to wear a perpetual scowl. The researchers have captured only two natives: the Sacramento splittail — a miniature torpedo with a forked tail fin — and the tule perch, an elegant, teardrop-shaped fish.

I’d read that the delta hosts many invasive species, but spending time on the water with Moyle and his survey crew brought that abstract notion to life. Native fish here are unique, beautiful, and constitute a struggling minority. The dominance of introduced species is one of the hallmarks of a novel ecosystem — one radically altered by human actions, to the point where many native creatures face an uphill struggle for survival.

Moyle and the student identify each fish and measure its length in millimeters before releasing it back to the water. As O’Rear records the data, he confirms each finding in affectionate terms. “A nice tule perch, 78. Threadfin shad, 66. Splittie, 163.” He greets a big carp like an old friend, calling it “Carpy-pooh.”

“The delta has an international mosh of fish, just like the human population of California,” observes O’Rear. The striped bass, for example, was planted in San Francisco Bay in 1879, using fish brought from New Jersey. Stripers have thrived by feeding on whatever is available, whether it’s native salmon fingerlings or introduced crayfish. Meanwhile, humanity has driven native fish out of many areas where they were once abundant. When miners tore the Sierra hillsides apart, they sent a heavy load of sediment cascading into the rivers that feed the delta. Native fish, including Chinook salmon and steelhead, buried their eggs in the gravel, where they were smothered by clouds of sediment. Because striper eggs float and their larvae thrive in open water, they were able to flourish while their native counterparts in these areas dwindled. Overfishing to supply nearby canneries also played a role in the native species’ decline.

Moyle and O’Rear consider the striped bass, which has taken over many of the resources once consumed by native predators, an “honorary native.” Like salmon and sturgeon, the striped bass needs cool waters for spawning. And like Delta smelt, juvenile striped bass feed on zooplankton. Because they hunt silvery fish that move in schools, stripers are not a threat to smelt, which swim solo and prefer silty waters that help them remain invisible to predators.

The Delta smelt has traditionally been seen as a vital indicator of the estuary’s overall health, but the species is now so rare that it can no longer serve that role, says Moyle. “If the smelt still survives, at least you know some of the best estuarine habitat is available — cool, tidal, food-rich,” he notes in an email. “Ironically, the best indicator species today, at least among the fishes, are non-native striped bass and American shad. They are still abundant enough to be measurably sensitive to environmental change at fairly short time [and] spatial scales.”

Over the decades, Moyle and other scientists puzzled out the Delta smelt’s quirky and complex life history. Though they are weak swimmers, the smelt migrate long distances across the delta by surfing on tidal currents. They thrive in turbid water; a thick load of suspended silt and algae forms a background against which the smelt’s prey, copepods and other tiny zooplankton, stand out. In winter, adults move upstream following the flush of silty water washed into the delta by the season’s first heavy rains. They spawn in shallow fresh water; then the adults die. In spring, juvenile smelt are carried west to the zone where fresh water mixes with the saltwater of San Francisco Bay. There they feed on abundant zooplankton, and grow to adulthood.

That, at least, was the outline of a typical smelt’s life in the pre-settlement estuary. Conditions could change drastically from year to year. In times of flooding, the low salinity zone that supports growing smelt would move farther west; during dry years, it would migrate inland. Still, somewhere in the delta’s vast maze of wetland and tidal waters, smelt could always find the habitat they needed for each phase of their life cycle. An ability to locate the sweet spots in an ever-shifting ecosystem was essential to the fish’s survival. In a species that lives for only a year, one disastrous season could wipe out most of the population.

Today, those sweet spots are increasingly rare.

“The Delta smelt,” Moyle and others wrote in a 2016 paper, “is well adapted for an estuary that no longer exists.”

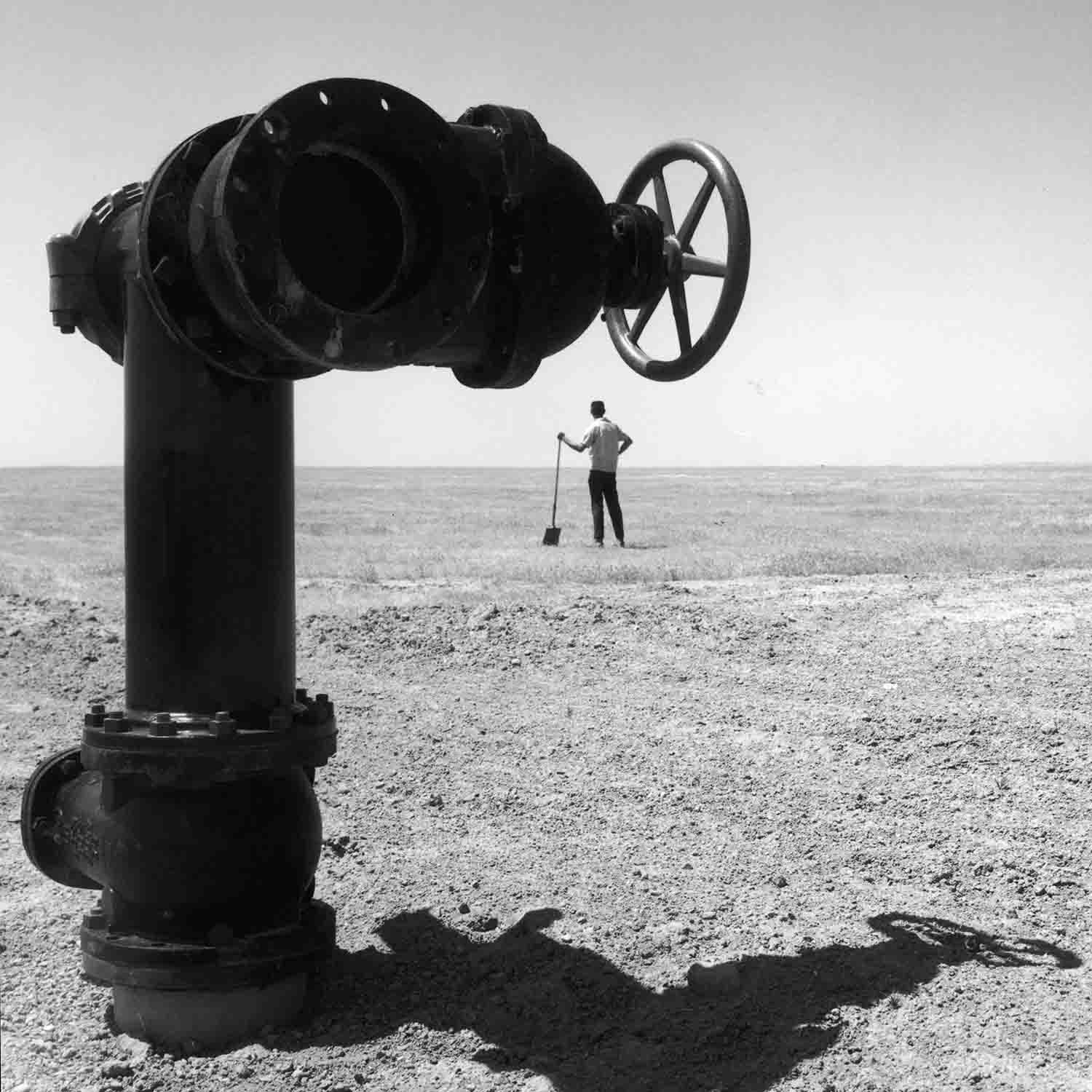

The smelt’s decline cannot be blamed on any single cause; it is the result of an onslaught of change. The transformation began in settlement times, during the 1850s, and accelerated in the twentieth century. In the last 50 years, mass diversion of the waters that formed and sustained the delta has been the most critical change. The region once received half of California’s total stream flow; today about 30 percent of that flow is diverted before it ever reaches the delta. A large stretch of the San Joaquin, the major river flowing into the delta from the south, has been drained dry.

The southern delta contains two of the largest water diversion systems on the planet. The federal Central Valley Project (CVP), a massive series of dams and canals that channel water from the far reaches of northern California to the delta and export it to southerly cities and farms, began operating in 1940. The State Water Project (SWP) went online in 1968; together the CVP and the SWP export water from the delta south to supply some portion of the needs of more than 27 million people and 3 million acres of farmland. The monster pumps of the two water projects can jointly move billions of gallons of water per day.

The amount of water flowing through the delta and out to San Francisco Bay is thus much reduced, to the detriment of many native fish. Along with these changes has come a continual influx of invasive species, from plankton to clams, fish and aquatic plants.

Smelt evolved to ride river currents into the delta, then surf the tides up and downstream in search of food. “Smelt need a really active system,” explains Moyle, “one where fresh water mixes with salt water, where the tides and the river work together to create habitat for the fish.”

That’s harder and harder to find in the delta.

Conditions in the central and south delta are especially dire. There’s little river flow — and that means there is little of the turbidity smelt are adapted to. What does flow out of the San Joaquin is farm runoff, heated and polluted as it trickles through the fields. The water is too warm for smelt. The still, warm waters have encouraged the growth of invasive Brazilian waterweed and water hyacinth. These alien plants further alter the habitat, slowing the movement of water and causing what silt remains to settle to the bottom. Introduced largemouth bass, popular with anglers, thrive in these conditions. Smelt die.

The giant water project pumps draw water from the Old River, a tidal channel that intersects the lower San Joaquin. They move so much water that they often reverse the normal northbound flow of the lower river. These reverse flows pull water from the northern delta south, toward the pumps. In the process, smelt in the north delta, which is fed by the cooler waters of the Sacramento River, can be dragged south.

Visual: FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

To the west, Suisun Bay was once a major nursery for Delta smelt. Now many smelt can no longer find enough food there to sustain them. A major cause of this problem is the overbite clam, a finger-nail size beast native to east Asia. The first overbite clams were found in Suisun Bay in 1986. The species spread fast, carpeting some parts of the estuary floor at densities up to 4,800 clams per square foot. This massive population of overbite clams filters most of the plankton out of the water, depleting food supplies for Delta smelt and other open-water fish, including juvenile striped bass.

In the last 15 years, Delta smelt have been discovered living in unexpected habitats, including Liberty Island, one of many man-made islands built in the delta to create farm land. Liberty Island flooded permanently in 1997 when its levees broke, and is now being managed for fish and wildlife habitat. James Hobbs, a research scientist at University of California, Davis, has found that some smelt stay at Liberty Island or at nearby areas in the north delta for their entire lives, growing up and spawning there. While initially this seemed like a hopeful sign, Hobbs fears Liberty Island may prove to be a death trap.

Smelt, he explains, are attracted by the turbid water in the shallows of Liberty Island. But those shallow waters heat up in summer, reaching temperatures that can stress or kill the fish. Before the north delta was tamed, smelt swam in deep, winding channels, shaded by tall stands of tule. The waters there stayed cool enough to sustain the fish year-round. Climate forecasts predict that under current conditions, much of the north delta will become too warm for smelt within the next 50 years.

Efforts are underway to change course. California’s EcoRestore program, for example, aims to create 30,000 acres of fish and wildlife habitat in the delta by the year 2020. The program’s goals are based in large part on habitat requirements spelled out in the biological opinions for endangered Delta smelt and salmon — though restoring habitat for native species in the modern delta remains a complicated mission.

Restoration ecologists are experimenting with ways to build wetlands in man-made islands. Such efforts can create habitat for native fish and wildlife, but will require active management.

Another promising effort is the Nigiri Project, which uses flooded rice fields at the edge of the Yolo Bypass to create habitat for juvenile salmon. The Bypass, built as a flood control device on the lower Sacramento River, is one of the last active floodplains in the Central Valley. Flooding takes place in the winter, when the rice fields are fallow. Experiments have shown that the fields become a food-rich habitat, where young salmon grow at the fastest rates ever recorded in the area.

The Delta smelt biological opinion emphasizes the need for tidal habitat, which sustained the species in the pristine delta. But Moyle says that restoring tidal flow is not enough. In 2006, the California Department of Water Resources breached the levee surrounding a former duck club in an effort to restore tidal marsh. When Moyle and his colleagues studied the resulting habitat, known as the Blacklock Restoring Marsh, they found it invaded by exotic plants and fish, including the Mississippi silversides, which preys on the eggs and larvae of Delta smelt. Native Sacramento splittail and tule perch swam in adjacent sloughs and managed wetlands, but not in the restored marsh.

The lesson: Creating habitat for native species in the modern delta will require invention and adaptation — and on many fronts, abandoning notions of “smelt habitat” that pre-date human settlement.

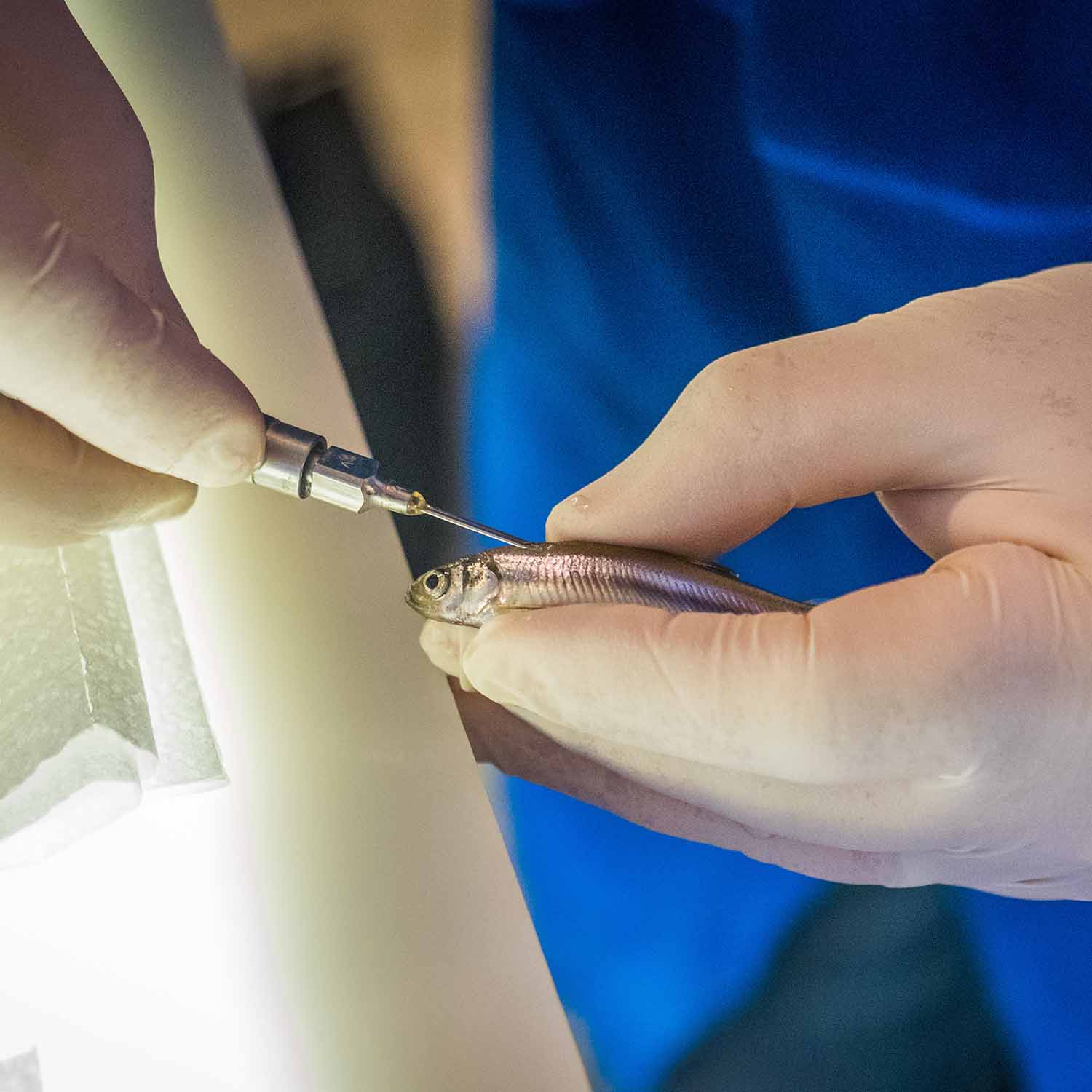

If he had the power to call the shots, Moyle says he’d give up on some parts of the Delta smelt’s traditional habitat entirely, mainly those in the south and central delta. Instead, he’d focus on improving smelt habitat in the north delta, so that the fish could survive there year-round. Through efforts like the Nigiri Project, he’d try to recreate floodplain and marsh habitats that foster the dense populations of zooplankton that once fed the smelt. Then he’d take smelt raised in captivity and carefully release them in the highly-modified wild — though he describes this as a “desperation move.”

The case of the Delta smelt has unleashed a flood of argument over what truly matters enough to merit allocation of California’s water. Like some other species protected under the Endangered Species Act — the northern spotted owl, the gray wolf — the smelt has become the target of intense resentment.

“It would take about four average size minnow buckets to hold 305 3-inch Delta smelt, yet that is the number of minnows responsible for diverting enough water to the ocean to provide a year’s supply for 800,000 California families,” wrote Harry Cline, a Fresno-based reporter for The Western Farm Press, in 2013. (Smelt are not members of the minnow family, but for some opponents of ESA-based water regulation, the label seems to sum up the fish’s perceived insignificance.) That winter, smelt caught up in the backward flow created by water exports triggered restrictions on the use of the CVP and SWP pumps.

“To protect smelt from water pumps, government regulators have flushed 1.4 trillion gallons of water into the San Francisco Bay since 2008,” wrote Allysia Finley, an opinion editor at The Wall Street Journal, in 2015. “That would have been enough to sustain 6.4 million Californians for six years. Yet a survey of young adult smelt in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River delta last fall yielded just eight fish, the lowest level since 1967.”

“Herein is a parable of imperious regulators who subordinate science to a green political agenda,” she continued. “While imposing huge societal costs, government policies have failed to achieve their stated environmental purpose.”

For some in the cities and farms south of the delta, which rely on exported water, it’s a popular assumption that water held back from export and allowed to flow west through the delta is wasted. But that notion ignores not just the estuary’s ecology, but the reality of the state’s water supply system.

Historically, saltwater flowed inland during summers and mingled with the western edges of the delta. With the completion of the two major water projects, humans gained the ability to engineer flows of freshwater in a way that pushes the bay’s salt tides back to the west, out of the delta. California’s water supply system relies on this key bit of manipulation: Managing rivers from the Sierras to the delta, and keeping enough freshwater flowing to push saltwater out of the delta. In dry years, for every acre-foot of water pumped by the CVP and SWP, an equal amount of water has to flow out of the delta to hold back saltwater. At times, this engineered balance requires restrictions on the amount of fresh water exported to the south.

Keeping water fresh at the export pumps, and at other water diversions around the delta, takes an outflow of about 4 million acre-feet per year. But officials have not traditionally separated out water needed to keep the delta fresh from water required to protect smelt, salmon and other fish. In water accounting, all have been lumped together as “environmental water.”

Greg Gartrell, recently retired assistant general manager at the Contra Costa Water District, is lead author of a report on water accounting in the delta published by the Public Policy Institute of California. The goal of the report, Gartrell says, is to “reduce the heat and smoke and shine some light on things. So that going into a drought next time, people understand what’s being done and why.”

Fish protection’s impact on water users varies year by year and month by month. In 2014-15, during the height of the recent record-breaking drought, export reductions aimed at keeping the delta fresh comprised about 3.5 million acre-feet. Only 400,000 acre-feet were dedicated to fish — or about 10 percent of the total.

The Westlands Water District, the largest agricultural district relying on water from the CVP, received a zero allocation of water in 2014-15. As a result, 220,000 acres of farmland went unplanted — about one third of the district’s total acreage. “We can point back to the biological opinions that take priority over water deliveries,” says Gayle Holman, a public affairs representative at Westlands. “The biological opinions dictate how water is going to be pumped or if it’s allowed to pump. So it has directly curbed water deliveries on the west side.” Holman attributed growing restrictions on water exports over the last 20 years to the Delta smelt. Ironically, she also emailed me a graph showing that the Delta smelt biological opinion, issued in 2008, is just one of the most recent of an array of environmental regulations since 1990 that limit pumping by the CVP. Among these is Decision 1641, a water quality plan adopted in 2000 under the Clean Water Act, which spells out the requirements for keeping delta water fresh.

During the spring of 2016, San Joaquin Valley farmers complained of pumping limitations. Then-presidential candidate Donald Trump pledged to bring more water to the valley, and mocked efforts to “protect a certain kind of 3-inch fish,” during a May 2016 campaign stop in Fresno. (In fact, pumping limits at the time were meant to protect Chinook salmon, as well as smelt.) Of the water allowed to flow downstream instead of being pumped south that April, about 66 percent was meant to keep the delta fresh, while 33 percent was for fish protection.

These jabs at smelt protection illustrate another downside of the ESA’s current approach: A single endangered species becomes the focus of anger when conservation clashes with human wants and needs. The smelt, which survived for millennia by remaining invisible, now makes an easy political target — and allows some to ignore the delicate balance that makes export of delta water practical. Saltwater can’t nourish crops or slake the thirst of southern California’s cities.

“I think we could start losing both species and farms if we don’t get this right,” Gartrell says.

In late December 2017, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife revealed that its regular fall survey of the delta’s waters had captured a total of two smelt, the lowest in the survey’s 50-year history. The following week, the federal Bureau of Reclamation, which oversees the CVP, announced its intention to change the way California’s water is managed in order to maximize water deliveries south of the delta. The proposal represents the Trump administration’s first effort to make good on the president’s Fresno campaign promise. It’s expected to trigger an intense battle with California politicians and regulators, many of whom make it a point of pride to resist the administration’s drive to dismantle environmental protections.

Moyle has spent a lifetime witnessing the overwhelming obstacles facing California’s native fish — from the state’s many dams and water diversions to climate change, which is warming the rivers and accelerating population declines. He’s also witnessed the failure of the ESA to rescue them. “I wish I could say that once the Endangered Species Act kicked in, everything got better for California fishes,” Moyle wrote in a 2013 op-ed in the Sacramento Bee. “But it hasn’t.”

Moyle credits the historic legislation with shaping his career, calling it the “‘thin red line’ in the battle against extinction.” The law remains a bedrock in conservation. But he is among a growing number of scientists who have come to understand that nature cannot be rescued one species at a time.

The delta recovery plan Moyle wrote in 1995, which recommended conservation based on the needs of all the region’s native fish, has gathered dust as fish populations continued to dwindle. Now he sees that conservation may mean protecting some introduced species along with the natives. If he could, he says, he’d revive his old recovery plan, and update it by including protections for the striped bass — an exotic creature that is now among the best indicators of the delta’s health.

“The reality is we have a novel ecosystem,” Moyle says. “We can manage it to favor the species we want — native fish, striped bass, American shad.” If you just let it go, Moyle says, invasive species will become even more dominant, with a handful of native species hanging on. But proper management can no longer amount to a narrow focus on the most-endangered fish, Moyle says. Conservations in ecosystems transformed by human actions must grapple with modern realities. These include drastic and sometimes irreversible shifts that make a return to pristine conditions impossible.

“We’re gonna lose more native species,” he warns, “if we don’t change dramatically.”

UPDATE: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that saltwater historically flowed into the delta as far as Sacramento. While some saltwater is known to have historically mingled with the western edges of the delta, it did not intrude as far as the state’s capital. The story has been updated.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Running this fountain is outrageous and irresponsible, a bad example!

Somehow we missed this last year. It is a beautiful, well done piece. Thank you.

Thank you for this highly informative article

Smelt isn’t as lovable as salmon or polar bears, nor is it a very phot0genic poster-fish for the San Francisco Estuary science and water community’s extraordinary efforts to confront the ecological imbalances of our time. But for decades people like Peter Moyle have helped Californians think of native fish as as worthy of our attention as where our drinking water comes from (the same place smelt live) or the latest advance of the white walkers (as inexorable as the invasion of our estuary by alien snails, overbite clams, microplastics, concrete, atmospheric river runoff, mercury, toxic algae, and hotter water). Wonderful to see such an in-depth, personable science story in a new venue about something our reporters at ESTUARY News have been covering for 25 years– for more deep dark stories about smelt try Options for Orphans by Kathleen M. Wong (http://www.sfestuary.org/estuary-news-orphans/) or No Scapefish in the Drought Wars by Joe Eaton (http://www.sfestuary.org/estuary-news-no-scapefish/). Meanwhile, we salut undark and Levy for a really good read, and Moyle for continuing to speak fishy truths to power.

Hi, Mr. Moyle: I live in the redwood region and we are experiencing the same disregard for the coho salmon as the delta smelt. The problem is in how the redwood forest is managed by the state board of forestry. The amount of biomass that is left to sustain a viable forest ecosystem is less than 10% of it’s natural biomass. This has changed the ecohydrological cycle and effect summer/fall steam flows due to less storm water retention and aquifer recharge which have many adverse cumulative effects. The growth rate of the forest has also been declining along with the regions economy. When will the state of California realize that business as usual is not only fatal for the coho salmon but for the state as well. Ken Spacek

Welcome to the Anthropocene! Are we too far gone to ever hope to retain visages of the world we (homo sapiens) evolved in for over 300,00 years? E.O. Wilson thinks maybe not (but probably so). Change is the hallmark of evolution and extinction events create genetic bottle necks that forward the process and ironically lead to increases in biological diversity. Meddle with ecosystems if it makes you feel good (I do) but don’t expect redemption. Enjoy the bus ride even if it might be headed off a cliff!

Excellent t information. Every Californian should read this.

I appreciate your dedication and the work you put into this article so interesting. I grew am interest back when the snail darter was the highlight.