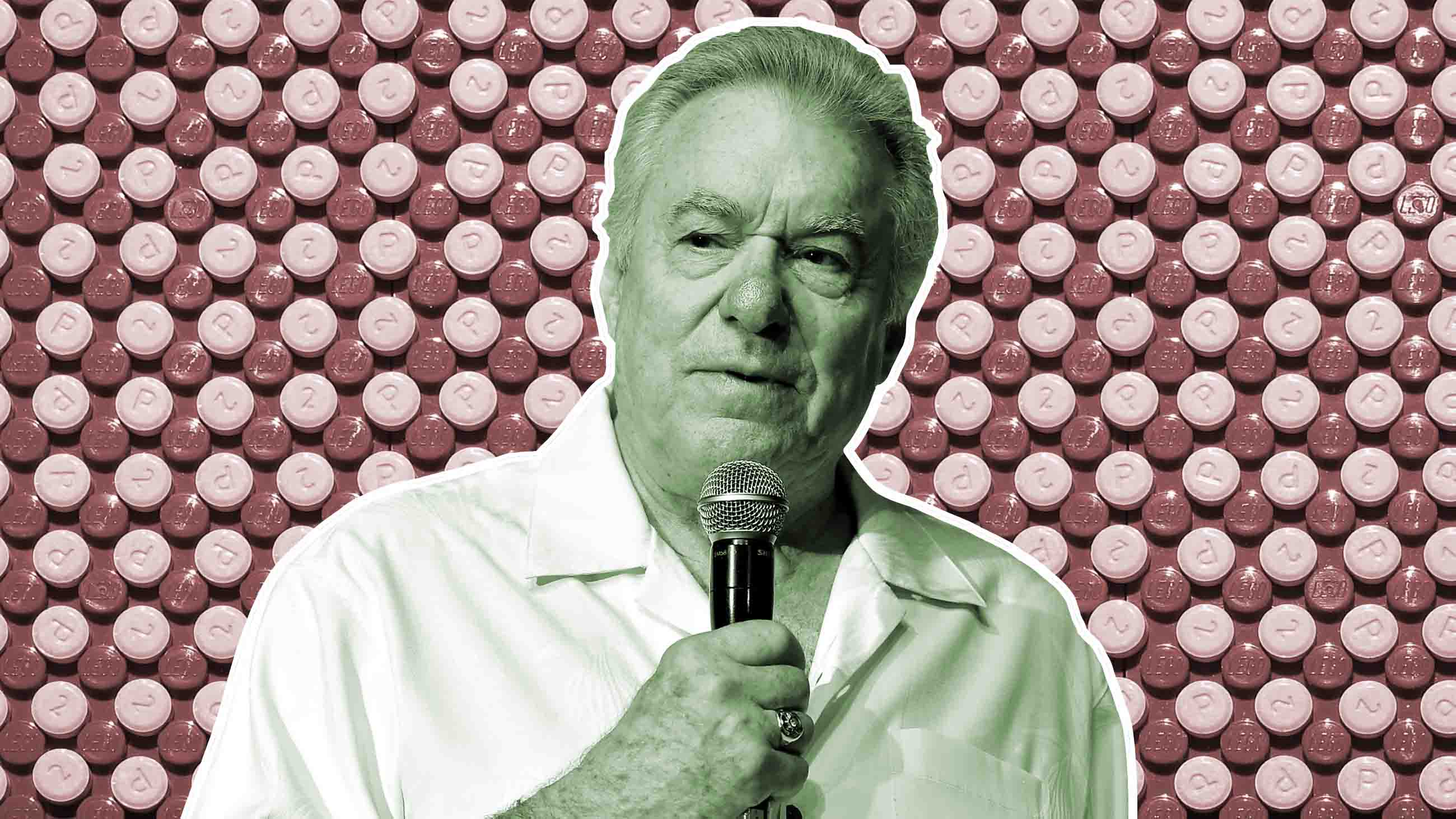

Affable Tycoon, Trump Supporter, and Champion of an Opioid Overdose Antidote

David Siegel’s crash course in the drug industry began on the worst day of his life: June 6, 2015. That was the day he and his wife, Jackie, learned that their 18-year-old daughter, Victoria, had been found unresponsive at the family’s home in Windermere, Florida. The Siegels, who had been attending a wedding in Park City, Utah, flew home.

Rikki, as the family called her, had been something of a flower child: Always barefoot, she pined for a Volkswagen bus and wanted to open her own sushi restaurant, the “Rikki Tiki Tavern,” on the Cocoa Beach Pier. She was also struggling with prescription medications, and had recently been to rehab. According to the medical examiner, she died of an accidental drug overdose. The drugs she had taken included methadone and sertraline.

David Siegel, right, with his wife Jackie. The couple lost their daughter to an opioid overdose in 2015, and Siegel now wants to make naloxone, which can quickly reverse the effects of opioids, “as common as aspirin.”

Visual: Denise Truscello via Getty

After her death, Siegel remembers thinking he had two options: “I could crawl into bed and pull the cover over my head and be a basket case.” Or, he said, “I could go out and do something.”

That something quickly became clear when, after his daughter’s funeral, he learned about naloxone, a medication that could have saved her life. Naloxone reverses the effects of opioids — drugs such as methadone, heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone, and other prescription painkillers. Opioids work by binding to receptors in the brain, and in high doses, they can slow breathing to the point of causing death. Administer naloxone to someone who’s unresponsive, however — as either a nasal spray or injection — and it acts as a powerful antidote, stripping opioid molecules off the receptors. Naloxone can bring people back from the brink of death.

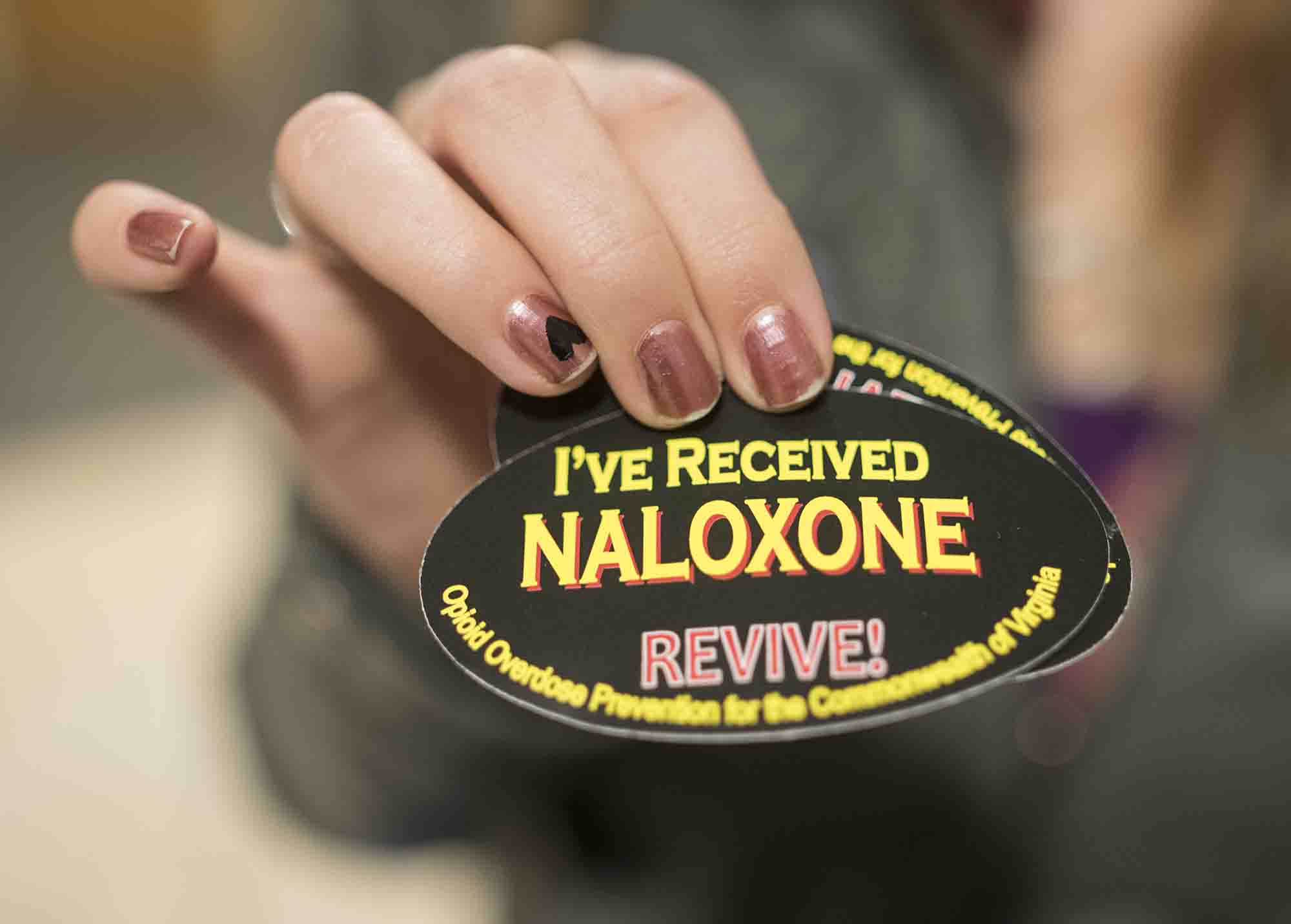

For all its potential, a web of federal and state regulations had long stymied access to, and even awareness of naloxone, but in the last two years, lawmakers have increasingly expanded access to the drug. As of this year, laws in all 50 states and Washington D.C. allow first responders — and, in some cases, civilian bystanders — to administer naloxone without the fear of legal repercussions. These laws, according to a paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, have been associated with about a 10 percent reduction in fatalities. In addition, President Donald Trump’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis recently called for a mandate that all law enforcement officers carry naloxone.

Siegel has publicly endorsed many of these measures, but a more fundamental problem remains: the escalating cost of naloxone. As it stands, the drug has been on the market since 1971, and several manufacturers have long sold injectable formulations, which are relatively hard for laypeople to use. By 2015, the Food and Drug Administration had approved two user-friendly versions, which are sold as brand-name Narcan nasal spray and the Evzio auto-injector. The former is available to law enforcement, health departments, and community organizations for about $40 a dose; a two-pack of the latter can cost as much as $4,500, but Siegel learned the active ingredient costs less than a dollar to manufacture.

This is where the 82-year-old, self-made multimillionaire, thinks he can make a difference. Siegel is the owner of Westgate Resorts, one of the world’s largest privately-owned timeshare companies. In 1998, he met Jackie, former Mrs. Florida, and the couple moved into an 8,000-square-foot house. When they married in 2000, Rikki, Jackie’s 3-year-old daughter from a previous relationship, tossed rose petals down the aisle.

The Siegels went on to have seven other kids and began building a 90,000-square-foot home, a project chronicled in the 2012 documentary film “The Queen of Versailles.” The film makes Siegel out to be an affable, outsized caricature of the sub-prime housing crisis who, among other things, paid a visit to the office of then-real estate mogul Donald Trump in an attempt to save the foundering, high-end resort complex Siegel was developing on the Las Vegas strip. Unhappy with the film’s portrayal, Siegel unsuccessfully sued the filmmaker for defamation.

After his daughter’s death, Siegel initially avoided going to Versailles as he took up the cause of drug addiction and overdose. In 2015, the family founded Victoria’s Voice, a private foundation that advocates for legislation designed to reduce access to prescription medications and encourage the co-prescription of naloxone — also a key recommendation of President Trump’s commission on opioids.

Siegel still drives to his company’s headquarters behind a taupe-colored strip mall in Orlando, but tells visitors he has turned over operations to his top executives. He maintains that his passion is no longer finishing construction on Versailles. Instead, his desk is piled with file folders and printed-out emails relating to his plan to flood the market with cheap naloxone, in an effort to put the antidote in the hands and noses of people who need it most.

“If somebody is laying on the ground turning blue — one breath from death – you give them a squirt,” Siegel said. “Within two to five minutes, they’ll be sitting up telling you what they took.”

Siegel says he believes it’s possible to undercut the competition by several orders of magnitude with a cheaper imported drug, and that he’s spoken with a business associate in China who offered to sell him a nasally administered form of naloxone for 60 cents a dose. “I’m going to bring it in for a dollar,” Siegel said. “I want to make it as common as aspirin.”

The odds of success on this front for Siegel — as unlikely a hero for naloxone and the greater opioid crisis as anyone might conjure — are far from clear, though his proximity to power seemed, at least for a time, a potential asset. Prior to the 2016 presidential election, Siegel made it clear he thought little of the drug czar who served under President Obama. “Goes around, makes a few speeches,” Siegel said. “The government has not lifted a finger with this epidemic. The weight of the presidency could end this epidemic.”

During Trump’s campaign, he claims to have bent the candidate’s ear. “I told Donald Trump, ‘If you get elected, I want to be the next drug czar.’”

Siegel did appear on stage at several Trump rallies, but despite maintaining that he had all the right connections in Congress and the White House, he was not named director of Office of National Drug Control Policy. Today, the post remains open; in October, Trump’s nominee for the role, Tom Marino, withdrew after The Washington Post and “60 Minutes” exposed his connection to pharmaceutical companies. (Despite a recent announcement of Kellyanne Conway’s involvement in Trump’s opioid strategy, her specific role has not been confirmed.)

In the meantime, Siegel has continued brainstorming, lending his voice to the chorus of those calling for expanded naloxone access. Over the last two years, he has spoken at events at the University of Central Florida and the Orange County Jail, as well as at bill signings in Tallahassee and Washington, D.C.

His plan to import naloxone from China is hypothetically feasible, but it remains to be seen whether Siegel can channel his personal grief and enormous wealth to ultimately flood the market with cheap naloxone.

Rikki Siegel was one of 52,404 drug-related deaths recorded in 2015, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and opioids were involved in the majority of those deaths. Many of the fatalities, whether from legally prescribed painkillers or heroin and fentanyl, are considered accidental. “I don’t think [Rikki] had any intentions of killing herself,’’ Jackie Siegel told ABC News. “I think she just wanted to soothe the pain she was going through.”

As David Siegel set about educating himself, he spoke with the surgeon general and officials at the Drug Enforcement Administration, as well as visited rehab facilities and talked to “former addicts in recovery.” He quickly realized that naloxone was not a cure-all: it does not treat substance use disorder, the chronic underlying condition, which can take years to treat. But he came to see how denying naloxone would be like refusing to give insulin to patients with diabetes, or nitroglycerin to someone, as Siegel put it, with heart trouble.

Not long after he helped campus police at the University of Central Florida procure several thousand dollars’ worth of naloxone, Siegel says law enforcement officials were telling him things like: “We would carry it, but we can’t afford it.”

Insurance companies negotiate rebates, and while many patients covered by health insurance are buffered from price increases, Dr. Phillip Coffin, director of substance use research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, said naloxone’s cost puts the most significant strain on the community-run outreach programs serving the under-insured and uninsured. “Most of these service programs are tiny,” Coffin said. “They need naloxone that is really, really inexpensive.” (The head of Baltimore’s health department said this summer that, because of costs, the city would begin rationing Narcan.)

Efforts to expand access to naloxone have been contentious — some argue there’s a lack of empirical data, and others argue that it bypasses the doctor-patient relationship — but they resonate with nonprofit organizations such as the Harm Reduction Coalition, along with public health officials. In 2016, the New England Journal of Medicine published an op-ed written by a group of researchers at Yale and the Mayo Clinic arguing against the high price of naloxone. Among their proposed solutions: “Importation of generics from international manufacturers that have received approval from regulators with standards comparable to those of the FDA.”

Leo Beletsky, a drug policy expert at Northeastern University, said, “Honestly, I’m more surprised that it hasn’t happened already…. It’s available abroad for less than a dollar a dose.”

But compromising on cost could potentially compromise safety, according to Dr. Roger Crystal, the CEO of Opiant Pharmaceuticals, the company that developed Narcan nasal spray. (The product is marketed in the U.S. by the company’s partner Adapt Pharma.) Crystal said Narcan was priced as cheaply as possible. In terms of safety and simplicity of use, Crystal believes that lower-priced competitors would almost certainly offer suboptimal dosing and treatment. “Because it’s suboptimal, it won’t work as well,” Crystal said. “How do you define not working? Unfortunately, that’s when someone dies. There’s a real responsibility here.”

But Beletsky argues that the bar for safe manufacturing and labeling is set high, especially for sterile injectable formulations of naloxone. “None of these problems are insurmountable,” he told me, adding that, in countries such as Ukraine, naloxone retails for 40 cents.

Last summer, Siegel traveled to Washington to lobby for the $181 million Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which included $200,000 in grant funding specifically for naloxone. That day, he remembers meeting another woman, who said her 34-year-old daughter had come home one evening, gone to bed, and an hour later was dead. “‘Do you know what naloxone is?’” Siegel remembers asking her. “She said, ‘No, what is it?’ I said, ‘Unfortunately, if you had known what it was, your daughter would probably be alive today.”

“That story can be told thousands of times,’’ he said. “People should not be dying out of ignorance.”

The walls of Siegel’s office are plastered with grip-and-grin photographs showing him with dozens of celebrities. Bill Clinton. Trump. Newt Gingrich. Arnold Schwarzenegger. Dolly Parton. The lion that, he said, modeled for “The Lion King.”

Below the photos, he keeps a large poster: On the left side, a neon green image depicts a normal 17-year-old’s brain; on the right, a similar scan pocketed with dark spots carries the label “Smoking Marijuana Weekends 2 Years.”

“Looks like it’s been shot with a shotgun,” Siegel said.

Siegel feels that cannabis not only damages the brain, but is a gateway drug. He has advocated for mandatory drug testing in middle and high schools as well as colleges, and believes the best way to stop the drug abuse is to prevent people from using drugs in the first place.

It was a sentiment that came up during one of Trump’s campaign stops in New Hampshire, just before the GOP primary. The candidate acknowledged that his brother, Fred, had succumbed to alcoholism, and said, “the way to shake the habit is not to start.”

Siegel endorsed Trump, and many of his positions on fighting drugs. “We’ve got to build that wall,” Siegel told me. “We’ve got to keep it from coming in from Mexico where most the drugs come.”

He also feels that drug dealers who sell fatal doses of drugs should be charged with murder, although that position is arguably counterproductive: Sociologists have found that criminalizing overdoses deters people from seeking help and calling 911.

Siegel is no stranger to controversy. Westgate’s high-default loans and high-pressure sales tactics have been the target of lawsuits, and he’s been accused of selling mortgages to people who could not afford them. He paid $5.4 million after being found guilty of battery related to sexual harassment in 2008. He also sent a letter to his employees hinting at layoffs and his subsequent retirement in the Caribbean if Barack Obama was elected President — something he did not follow through on.

Nonetheless, Siegel maintains that his anti-drug campaign is purely altruistic. “I’m not in the profit-making business when it comes to drugs,’’ he said. “I want to save lives.”

He claims that he is not deterred by cost and vowed to cover, out of pocket, the $70,000 submission fee — the first step in importing a new drug — “if that’s what it takes to keep 40,000 people from dying in the next 10 months.” So far, though, Siegel said he’s been underwhelmed by the prototype devices he’s been shown.

The President’s commission on opioids recognized the severity of the crisis, writing that “America is enduring a death toll equal to September 11 every three weeks.” Despite their recommendations to focus on treatment, Trump’s policies have focused on supply-side interventions. The administration’s efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which was expected to gut Medicaid and defund one of the nation’s top sources for addiction treatment, elicited a strong rebuke from Roy Cooper, a commission member and governor of North Carolina. Cooper said, “If we make it harder and more expensive for people to get health care coverage, it’s going to make this crisis worse.”

When I last spoke with Siegel in October, he remained frustrated by the government’s inaction. “The pharmaceutical companies are in everybody’s pocket,” he said. “I’m very disappointed. I need to get up there and meet with them.”

Nearly a year had passed since the election, he said then, “And what have we done? No wall. No drug czar. No action. I don’t know.”

Everywhere he goes, Siegel said he sees signs of a deepening crisis. The morning we last met in Florida, he said Jackie had called him from Beverly Hills. She was getting her hair done. “She’s talking to her stylist, who said her 20-year-old sister died of a heroin overdose. There’s no one that is immune. Everybody. I’m sure you know somebody who has a drug problem or died from a drug overdose. I mean it’s horrible.”

Siegel acknowledges that naloxone was not a cure-all for opioid use and addiction. It simply keeps people alive, but a pulse is a prerequisite for treatment and rehabilitation. “Fifty-thousand people died last year from a drug overdose,” Siegel said. “Every single one of them could have been saved if they had known about naloxone or had access to it. This is not terminal cancer we’re talking about.”

Peter Andrey Smith is a freelance reporter in New York exploring the unseen, underrepresented, or purposely obfuscated processes that transform our world. His stories have been featured in The New York Times Magazine, Outside, Harper’s, Scientific American, Wired, and The Walrus, and online at The New Yorker and Buzzfeed, among other outlets.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Also do you tycoons think about how people are yanked off their medication so barberic…why don’t you think about people who truly need their medication…you should have been advocating spending time with your lovely child…don’t blame the medication

Great article. I’m thankful to live in the UK. I lost 100 plus friends to opiates. Now we have methodone and Naxalone. Anyone can walk in to a clinic and obtain naxalone and instructions for the use. It costs pennies a dose. Charging 4,500 is murder. Literally murder.

This man’s billions come from a company who’s business model is to lie, pressure, and imprison ppl for life. I wonder how many victims of Westgate Resorts have began addiction, over dosed, or committed suicide bc they were so deeply in debt with his company they lost hope. They offer no real options, there is no way out that doesn’t cost $1000s.

Search : Westgate Resort Complaints if you think I’m an internet crazy.

My guess, Mr. Siegel has heavily invested his victim’s money in this “noble cause” and will profit handsomely somewhere in the fold.

Millionaires donate to charity as tax write-offs, Billionaires use charity as another revenue source.

I’m sorry Mr. Siegel’s child lost her life at such a young age. I have no doubt that pain is very real and would not wish that on anyone, even Mr. Siegel. However, this man and the business tactics his company uses have literally ruined people’s lives. With his wealth, he could change his business structure at any given time and leave a legacy that impacts millions positively while still profiting handsomely. Then again, why would the snake oil salesman actually sell a cure when he profits so much more selling false hope. I mean there are other noble causes in one’s life….like building the largest home in North America, then gloating it on a reality tv show so all the world can see. It’s that kind of shallow, self absorption that leaves me highly skeptical of his pure intentions in this article. Bravo Mr. Siegel, bravo.

Great article on a critically important problem that we can solve. Key to saving lives with naloxone is to solve the dual problems of cost (sell it as cheaply as possible) and access (sell it everywhere possible). Harm Reduction Therapeutics, is a nonprofit 501c3 pharma company working to take intranasal naloxone over-the-counter and sell it at cost: http://www.harmreductiontherapeutics.org.