In a Colombian Family’s Dementia, a Journey Through Race and History

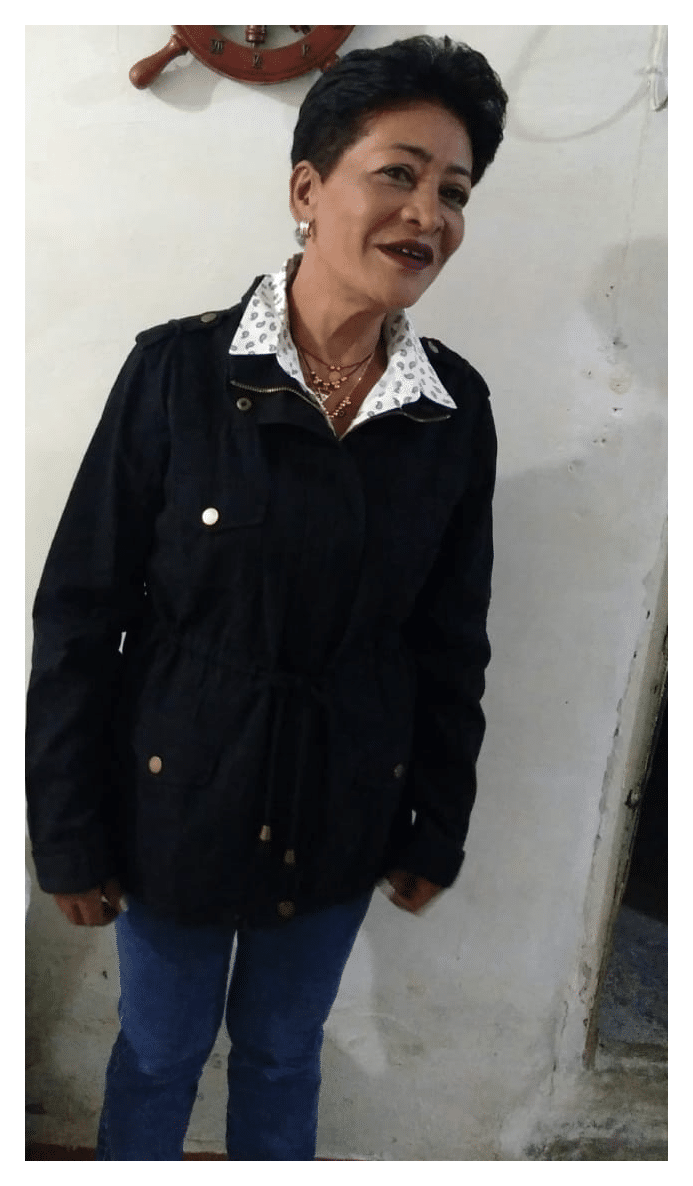

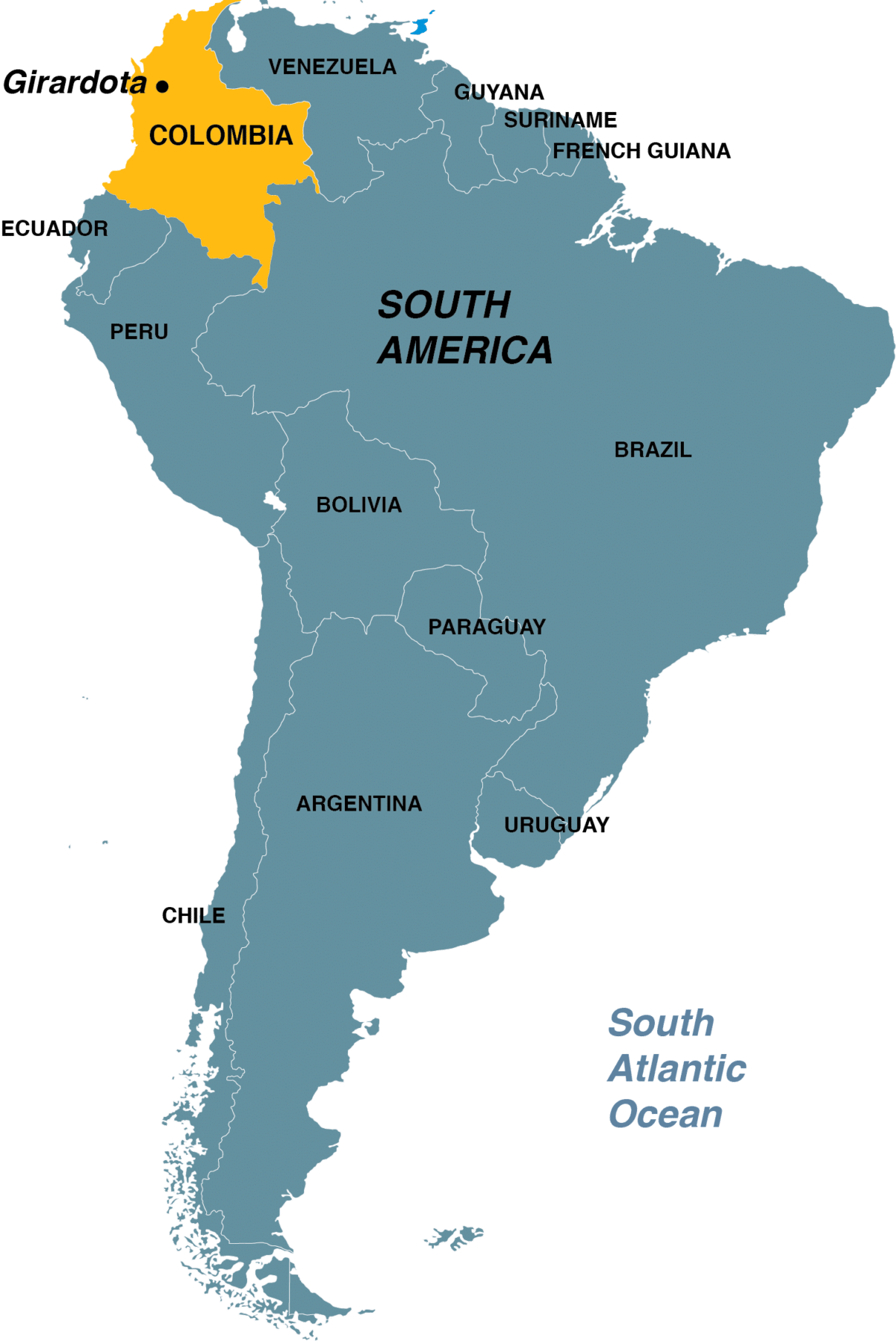

Piedad’s house sits above the cemetery in Girardota, Colombia, just north of Medellín. From her front porch, the view gives way to green hills, each home to hamlets with sugarcane plots and tile-roofed houses tucked in among the trees. One of these hillside hamlets is where Piedad and her 11 siblings grew up. Their father, Horacio, worked in cane fields and sugar mills, and their mother sold fruit from her orchard; their grandmother made pots from clay she dug across the river. When earthquakes destroyed their home in 1979, the family moved into town and left rural life behind.

Horacio showed the first symptoms of dementia soon afterward. He ignored the food he was served and got lost returning from church. He grew aggressive and delusional, and Piedad would return from her job at a sugar-packing plant to help bathe him, holding back tears as he kicked and punched. Horacio died in 1984 from what his doctors called senile dementia, the same disease that killed his father and three of his siblings.

By the early 2000s, four of Piedad’s own siblings, then in their 40s and 50s, were showing signs of dementia. A local doctor referred them to a group of investigators in Medellín who studied families with a unique genetic mutation that causes early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nicknamed the Paisa mutation after the people of Colombia’s Antioquia region, who call themselves paisas, it occurred on a gene, called presenilin-1, implicated in familial Alzheimer’s. The families affected tended to be white farmers living in remote mountain towns that felt untouched by time.

At 67, Piedad has dodged her siblings’ fate. But after decades of tending to people who can never be left alone, she finds herself anxious even blocks from home.

Whenever a cluster of potential new cases appeared, the Medellín investigators, led by neurologist Francisco Lopera of the University of Antioquia, sent a field team to the family home or farm. In the spring of 2002, Lopera’s team converged at Piedad’s house to draw blood, administer pencil-and-paper tests for cognitive impairment, and sketch genealogies. The assumption, Lopera said, was that the family was a remote branch of the Paisa mutation clan. Their disease showed the same pattern of inheritance, passing from a parent to half of his or her children; a similar age of onset; and a progression typical of Alzheimer’s.

Kenneth Kosik, then a neuroscientist at Harvard University and a close collaborator of Lopera’s, accompanied the team to Piedad’s house. He felt from the beginning that this family, which appeared to have a lot of African ancestry, might not be related to the larger one. Still, “I knew nothing about their story at the time,” he said of Piedad’s family, “and there’s a lot of variation in pigmentation all through Colombia so I didn’t focus on that.” In a country where nearly everyone can claim some mixture of African, European, and indigenous descent, it wouldn’t have been surprising to find a hidden link.

Yet when their blood samples came back, Piedad’s family was negative for the Paisa mutation. Something else — likely another presenilin-1 mutation — caused their disease. Years would pass before anyone would revisit the family’s samples to learn what the mutation was or where it came from. The Paisa mutation “was the only mutation we were set up to detect at the time here,” Lopera said. “And we were so focused on that family — it was such a large and important population — that it took up nearly all our resources.”

The Paisa mutation family went on to become a key research cohort for early Alzheimer’s, the subjects of dozens of studies and numerous media reports, and finally, starting in 2013, the basis of a clinical trial, which is still ongoing, to find out whether the disease can be prevented in people otherwise sure to develop it.

Piedad’s family, whose surname Undark has withheld in deference to local medical custom, could not be included in the trial, which recruited only Paisa mutation carriers and their relatives. Piedad went on to nurse, and then bury, five of her brothers and sisters. “I was the spinster,” she said, so the caretaking fell to her. At 67, she has dodged her siblings’ fate: She is clearly not a carrier. But after decades of tending to people who can never be left alone, Piedad finds herself anxious even blocks from home, eager to get back to her lace tablecloths and cigarettes, to her view of the cemetery where so many of her loved ones ended up.

Some 17 years after first meeting Piedad’s family, Kosik, Lopera and their colleagues are now bringing them to the attention of science. In a paper published online in the journal Alzheimer’s and Dementia in February, the scientists described the family’s mutation and disease, a step that will help them become eligible for future prevention trials to learn whether Alzheimer’s can be kept at bay. While Alzheimer’s most often develops after the age of 65 and is linked to a variety of factors, research leans heavily on families with early-onset, genetic forms of the disease to understand its progress and test therapies that might interrupt it.

The scientists have also discovered that Colombia harbors more Alzheimer’s-causing mutations than they originally thought — and the pattern may well extend even further. “We were always claiming that we were dealing with something special and unusual,” Lopera said. “The mountains, isolation, and so on.” He now suspects that not just Colombia, but the rest of Latin America is full of Alzheimer’s-causing mutations yet to be described. “We’re starting to see them reported in Mexico, in Cuba, in Argentina and Chile,” he said. “Though Colombia may well turn out to have more.”

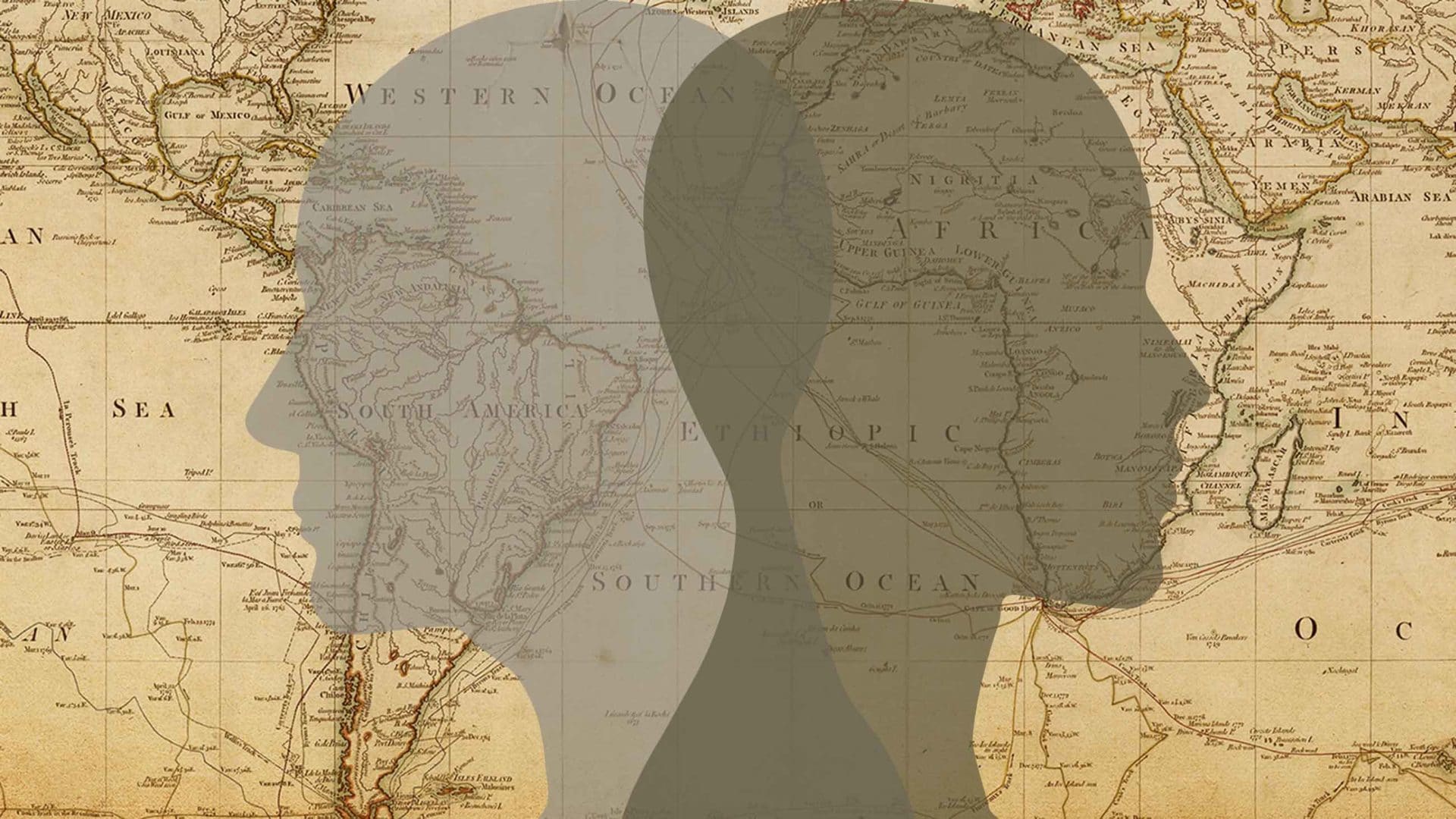

And in uncovering this one mutation’s African origins, the scientists have revealed a hidden story of blackness in a region that long ago decided it was white.

Well before Piedad’s family began to be formally studied, the possibility of a second Alzheimer’s-causing mutation in the region — and what it might mean — nagged at Kosik. After he’d moved to the University of California, Santa Barbara, he tested the family’s samples. He found another unique mutation, labeled I416T for its position on the presenilin-1 gene. These mutations are rare. And though Piedad’s family was smaller than the Paisa mutation clan — which had thousands of members — it was still larger than most early Alzheimer’s families.

Why should two families with parallel mutations co-exist in one tiny corner of the Andes? There were a few reasons, Kosik thought. The mutations could have been more common than scientists realized, and they were finding them just because they were looking. Something may have increased the mutations’ frequency in the local gene pool, though no one could say whether they’d arisen in Colombia or had been carried in by outsiders. Though there was a high rate of cousin marriage in rural Colombia, these mutations were dominant, not recessive, so it couldn’t be endogamy alone.

In 2013, the clinicians in Medellín began collecting genetic and health data from Piedad’s family. Of 93 adults who agreed to be studied, 26 carried the mutation and nearly half already showed signs of Alzheimer’s. Their cognitive impairment began at around age 47, progressing to dementia by about 51. “This is a little older than what we see in the Paisa mutation population,” said neurology resident Laura Ramirez-Aguilar of the University of Antioquia, the lead author of the recent paper. “But the disease — characterized by amnesia in the early stages — generally mirrors that of other populations with presenilin-1 mutations.”

To trace the origin of the mutation, the investigators collected genomic data, which would allow them to compare genetic patterns across many people and help answer a question that had long concerned Kosik and Lopera. “We were starting to believe that there’s an increased prevalence of rare mutations in Colombia,” Kosik said. “So if that’s true, how did they arise? Part of knowing how they arose is knowing where they came from.” With whole genomes, the team could look at the stretches of DNA surrounding the mutation “and align them, and show that all that entire region was all inherited as a block,” called a haplotype block, Kosik said.

Kosik and his colleagues had already done similar work with the genomes from the Paisa mutation family. That mutation, they learned, was nestled within a long haplotype block usually found in the DNA of people of European descent. The researchers found the Paisa mutation to be 15 generations old, which suggested origins in the 1600s — a time when Spanish colonists, nearly all of them men, poured into Colombia, seeking fortunes in gold. But the Paisa mutation had never been reported in Europe, suggesting that it either arose in the New World, or died out in the old one.

In 2018, Kosik and Juliana Acosta-Uribe, a Colombian physician and graduate student in genetics at UC Santa Barbara who’d previously worked in Lopera’s group, began using similar methods to find the I416T mutation’s origins. To start, they compared genomic data from Piedad’s relatives to a database of human genomes from all over the world, called the 1,000 Genomes Project. The family members were of mixed African and European descent, it turned out, with a small contribution of Amerindian genes. Nearly all had been born in Girardota or neighboring towns.

The haplotype block where their mutation occurred was exceedingly short. That hinted at an African origin. There’s more recombination on African chromosomes than on European ones, like a deck of cards that is more thoroughly shuffled. Over millennia this has translated to tremendous genetic diversity in Africa, even across close distances.

The researchers found no evidence of the I416T mutation in the 1,000 Genomes database, but they did identify people who shared the haplotype block. All were Africans or people of mixed-race African heritage — from Barbados, from the Southern United States, Nigeria, Sierra Leone. In samples from Gambia, in West Africa, the block was especially common. This could mean only one thing: The founder of this mutation was someone of African descent. While the Paisa mutation may have come in with a conquistador, this one had arrived with a slave, or arisen in his or her descendants.

Before the Spanish Conquest, the Girardota region was inhabited by the Nutabe, hunters and fisherman who grew corn, beans, and yucca and made earthenware from the same fine clay that Piedad’s grandmother later used. The Nutabe extracted gold from riverbeds and left traces of their cosmology in petroglyphs that still dot the hills. Little else of them remains. Spanish colonists began displacing and killing the Nutabe soon after settling here in 1620.

A couple decades later, members of those Spanish families traveled to the port city of Cartagena and returned with enslaved Africans who they hoped would do for them what the Nutabe would not: mine their streams for gold, raise their children and livestock, and cultivate their sugarcane, a crop that would soon become more profitable to them than gold. By 1665, more than 100 Africans were registered among Girardota’s estates, including men and women from what are now the countries of Guinea, Angola, and Gambia.

Visual: UNDARK

As in the American South, landowners’ surnames were imposed on the slaves, who became Cadavids, Londoños, and Castrillóns. The divisions between the black Cadavids and white Cadavids, the black Londoños and white Londoños, quickly blurred. In households where women were enslaved, “the white men took advantage of them, knowing there was nothing they could do,” said Juan de Dios Cadavid, a local historian who traces his roots to the Spanish settler Cadavids. In censuses from the 19th century, mixed-race individuals far outnumbered people described as either white or black.

“Black people in Girardota have always been a population at risk, and we developed strategies to survive,” said Jorge Mario Cadavid, a biologist with the University of Antioquia’s School of Medicine who lives in one of the town’s historically black hamlets. One of these, he said, was to continue working in white homes and farms long after slavery was abolished in 1851. “Our ancestors secured food and protection this way, keeping close to their former owners,” he said. Jorge Mario’s own mother worked as a housekeeper for a white family, and only when his father went to work on the railroad, leaving sugar behind, did his family break a centuries-old pattern of servitude.

“Another way we survived was by adopting elements of [white] culture,” Cadavid continued. Descendants of slaves wrote and performed sainete, a form of burlesque musical theater once wildly popular in Spain and the Spanish colonies. Sainete fell out of vogue among Girardota’s white townspeople, but flourished in the black hamlets, where it persists even today, “a European art form completely co-opted by Afro-Colombians, to parody whites.”

Sainete is one of Girardota’s proudest traditions, celebrated in a week-long annual festival. Oddly, though, a mural in the town square depicts few black people; a handful of sainete players and a local string band compete with legions of white politicians and priests. In the lower corner of the mural is the image of an unnamed black farmer half-hidden amid rows of sugarcane, as though unsure whether to come out or retreat.

African heritage remains a slippery subject even here, where — as elsewhere in Colombia — people tend to describe themselves in terms of physical, observable traits, not ancestry. Piedad, who has cinnamon-colored skin, refers to herself as morena, or brown. A person may identify as brown while describing a full sibling as white; anyone with deep skin and dark hair, regardless of heritage, can be described as brown or black. In Piedad’s family, members run the full gamut of color.

“To be afrodescendiente is first to acknowledge oneself as such,” said Jorge Mario Cadavid — and not everyone chooses to. While Piedad and her family share some of their region’s black traditions — her father played guitar for the sainete — they do not identify as afrodescendientes. “What’s that?” she asked about the word. “No. No one ever told us that and we never looked into it.” They identify simply as paisas — people from Antioquia.

Today, the Antioquia region is home to indigenous reserves, Afro-Colombian settlements on the coast and in former mining towns, a cosmopolitan population in Medellín, and white farming families in the mountainous east and northwest. But popular culture has deemed the last of these groups to be the most quintessentially paisa. The anthropologist Peter Wade, who studies race in Colombia, describes Antioquia as long harboring “a myth of racial purity and a lack of black and Indian heritage,” though in colonial times, Africans made up as much as a third of its population. In the early 2000s, a group of scientists in Medellín gave the conceit a boost when they began referring to paisas as a “genetic isolate,” describing a closed-off population largely European in its makeup.

The researchers took samples from doctors and students at the University of Antioquia’s medical school — an elite public institution — whose great-grandparents were all born in Antioquia. In 2000, they reported that the male ancestry in this group was almost exclusively European, with an African contribution of just 5 percent. The samples also showed a strong Amerindian signature from mitochondrial DNA, which is only inherited from mothers. The results indicated an early genetic pattern “involving mostly immigrant men and local native women,” the researchers wrote. As the native population crashed, they reasoned, European settlers came to have children with mixed white and indigenous women, increasing the European genetic signature.

Six years later, the researchers took samples from families clustered in a handful of old towns, and reported nearly 80 percent European ancestry among them — a figure higher than previous studies in Antioquia had shown. The towns in the study were long-known for being unusually white, but this is not why they were chosen, said geneticist Andres Ruiz-Linares, who led the studies. Rather, they had high rates of genetic diseases, which suggested isolation.

The local media seized on the racial implications of the papers, which seemed to affirm the inherent European-ness of paisas, and the widespread if baseless belief that if there was ever more than a dash of blackness in the population, it was a recent development. In an essay lauding the geneticists’ work, the newspaper columnist Fabio Villegas-Botero wrote that the paisas had been the group “whitest, in appearance, in all Colombia,” until an “influx of blacks and mulattoes” had, “with some notoriety,” begun to darken local complexions.

Wade, the anthropologist, wrote that the genetic isolate label “fits neatly with existing images of the paisas as special and different,” not to mention white. (In Medellín, where samples from the 1,000 Genomes Project found an average of 75 percent European ancestry, 93 percent of people identify themselves as white.) If the researchers had sampled more broadly, Wade wrote, “a different picture of the Antioqueño population would have emerged” — one with higher African and indigenous contributions.

In those years Lopera and his team found the concept of an isolate a compelling way to explain how the Paisa mutation had flourished. Antioquia, Lopera wrote in 2002, “is one of the few genetic isolates of the world; this fact gives us a competitive lead in the study and investigation of hereditary diseases.” His discovery of that mutation, among white farming families in remote highland towns, may have furthered the image of an isolated, European, and genetically uniform population — after all, they had a rare disease to show for it.

As he soon found out, though, they were not alone.

At her dining room table, Piedad shuffled through a pile of documents: ID cards of her dead parents, brothers and sisters; cemetery plot receipts; hospitalization records; copies of baptismal, marriage, and death certificates from the Catholic diocese of Girardota.

Years ago, when she began working with Lopera’s team, Piedad was relieved to learn that her family’s disease was genetic. Before, she said, people attributed it to witchcraft. When her brother Cenen grew forgetful and aggressive, neighbors said he’d been cursed or poisoned by an ex-lover. After another sister, Trinidad, couldn’t remember which color uniform to wear each day to the cafeteria where she worked, neighbors had the family convinced that someone was out to get them. “We were brainwashed into seeing ourselves the way others saw us,” Piedad said. “And we were so desperate that we went anywhere anyone told us to go for help, and wasted a lot of money on quacks.”

At Piedad’s table, Sonia Moreno, a neuropsychologist in Lopera’s group who specializes in mapping hereditary diseases, was working to extend the family’s genealogy, a sprawling chart spanning five generations. Moreno aimed to add a sixth, seventh, or even eighth, inching toward the mysterious founder of the I416T mutation.

Both Piedad’s father and her paternal grandfather, Indalecio, had died of early-onset dementia. From church archives down the street, Moreno retrieved a baptismal certificate revealing that Indalecio had been born in 1865 as a child out of wedlock, or hijo natural, to a woman named María Mathilde. María Mathilde, born in 1844, was also an hija natural, the daughter of a woman named Manuela and the granddaughter of a married couple named Pastor and Paulina. They would have been born around 1800, which meant that one or both of them might have been enslaved when they attended their grandchild’s baptism.

In the span of an afternoon, Moreno had uncovered three more generations. But church records went back no further, and many uncertainties remained. Without knowing the fathers of María Mathilde and Indalecio, or having any record of who had gotten sick, it was difficult to trace with whom the I416 mutation had traveled. To get all the way back to a 17th century ship from West Africa, Moreno would have to consult Spanish colonial censuses and other types of archives — and the chances of success were slim. But she was willing to keep going, and Piedad encouraged her to try.

“Let me understand something,” Piedad said as she and Moreno wrapped up for the day. “These illnesses that we have, that we suffer in Colombia, were brought by the Spaniards and the slaves that arrived so long ago?”

“Yes — more or less,” Moreno said. In fact, the story had recently become even more complicated.

There aren’t just two presenilin-1 mutations in Colombia. Kosik, Lopera and their colleagues have in recent years found nine more, across families ranging from just a few members to hundreds. Some of the mutations are considered “novel,” or never before reported anywhere in the world. Others have been reported, but in places as far-flung as Turkey, meaning they either arrived with immigrants or arose independently in more than one place.

One of the newly discovered families lives on Colombia’s Caribbean coast; another in an indigenous region; others in the country’s largest cities. Their mutations occur across a variety of ethnic backgrounds and mixtures yet to be fully explored through genomic studies.

Today, few researchers still describe Antioquia, home to nearly seven million people, as a genetic isolate, but rather a place that is home to many isolated populations and founder effects. “As we see in the genes there is no such thing as a paisa,” Kosik said. “The genetic fine structure is completely different depending on the family.”

Being an isolate “is not black or white, it’s not yes or no,” said Ruiz-Linares, a professor of genomic anthropology at Aix-Marseille University in France. From a genetics perspective, he said, the notion can be defined as a relative reduction in diversity, which may in turn lead to an increase in the frequency of rare mutations.

Kosik said the colonization of Colombia may have set the stage for this type of genetic drama to play out. “The genetic imprint of the original populations serve as a substrate of what you would call genetic isolates, all made up of indigenous groups that have been separated from each other for thousands of years,” he said. After the Spanish Conquest, which brought Europeans and Africans into the mix, “the next step was a bottleneck, a drastic drop in population” — in Colombia, indigenous populations declined 90 percent within a century. “Many people died and you ended up with a loss of diversity,” followed by a period of rapid population growth and no immigration. “Rare mutations became amplified — or at least that’s what I’ve come to believe.”

The mutation affecting Piedad’s family is yet unnamed — investigators still refer to it by its number, I416T — but Lopera thinks it, too, should be called the Paisa mutation. “What we really have are two Paisa mutations,” he said. “The African and the European.”

As scientists continue to unravel the genetic threads of her family’s disease, the stark math of it still haunts Piedad. Her youngest sister is now bedridden with late-stage Alzheimer’s, and a brother has developed dementia. When they die, Alzheimer’s will have claimed seven of her siblings.

“I’d love to think this all ends with us, with our generation,” Piedad said recently. “I don’t want to think about this mutation anymore.” But she also counts more than 150 nieces, nephews, second cousins, and their children. A few have already become sick. Each child of a mutation carrier, she knows, is at 50 percent risk of developing early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Piedad’s family is not as well researched as the Paisa mutation clan, who for more than 30 years have participated in a barrage of studies to help understand the natural history of their disease and have donated hundreds of brains for analysis. Some 250 members of that family are now enrolled in a trial to determine whether a drug that targets the protein beta-amyloid, which accumulates in Alzheimer’s patients’ brains, will prevent them from becoming sick.

Want more Undark? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter!

Researchers have yet to collect a brain from anyone in Piedad’s family, and just a few members have undergone brain imaging to track patterns of disease activity. None is enrolled in a clinical trial. But this could soon change. In October 2017, well before the I416T mutation was published, researchers from Washington University in St. Louis flew to Medellín to ask Piedad’s relatives to join the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network, or DIAN. DIAN combines smaller families with different presenilin mutations into a large study group to test new drugs that might prevent or slow Alzheimer’s.

About 50 people — many of them Piedad’s nephews and nieces — attended the meeting, eager to hear more. Older family members said they’d come to support the next generation, not themselves, that they wanted to “break the chain.” The researchers barely asked who was interested before being drowned out by shouts: “Everyone!”

Within a year, though, the manufacturer of the proposed experimental drug — another anti-amyloid agent — withdrew it over concerns of side effects, ending short-term hopes for a trial. In late 2018, DIAN researchers staged another meeting with Piedad’s family. There was no new drug candidate on the horizon — drug development for Alzheimer’s has been rife with disappointment — but the investigators wanted the family ready if and when a promising agent appeared.

A group of Piedad’s nieces sat front and center at that meeting, asking question after question. They wanted to be tested for the mutation; to enroll in studies; to take part in trials. This chain of theirs was centuries in the making, and they demanded the chance to break it.

Jennie Erin Smith is a freelance science writer based in Medellín, Colombia, where she is working on a book about families with Alzheimer’s disease. She is the author of “Stolen World” (2011).

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

This article is very important not only to understand the origin of such diseases, but also to understand our own history and background, people often consider themselves as members of a particular race and encourage racism not knowing that they could be genetically related to whom they discriminate.

My grandmother age 103 is currently suffering those symptoms and we allways say it’s her age.

Thanks for this publication, saludos desde Barranquilla, Colombia.

Hola, excelente informe. Me gusta leer sobre esta enfermedad ya q mamà tuvo sintomas del alzheimer tenia 88 años cuando murió en el 2018, sintomas de agresividad con migo como hija ya q era yo la q permanecia con ella todo el tiempo la cuidaba, preguntava todo el tiempo por la hora, el día en q estavamos, con mucho frio, veia cosas q nosotros no la veimos. Aunque ella no murió por esta enfermedad si no por una obstrucción intestinal. Para mi fue muy triste verla en esas condiciones de olvido, se enojava tambienpor q no la entendia. Conosco dos señoras o me an contado de estas personas q padecen de esta enfermedad y llevan mucho tiempo, una 8 años y otra 4 años, triste conocer la historia de estas dos personas y también de sus familias ya q el cuidado de ellas es permanente y desgastante para los cuidadores. Ellas viven al norte de la ciudad de Medellín, en el barrio Castilla y la otra señora nor occidente de Medellin. Actualmente vivo en una Vereda al norte de Antioquia empesando el municipio de Barbosa, llevo apenas 6 meses viviendo en esta, y precisamente hay una señora con principios de esta enfermedad es de raza negra, anres habia leido q es muy común esta enfermedad en el departamento de Antioquía, al norte de este departamento, y a la raza negra, cabe recordar q mi mamà era de raza negra. Los felicito por llevar acavo esta investigación deseando de todo corazón se logre el objetivo a feliz termino. Felicidades DIOS LOS BENDIGA.

Very well documented and beautifully written. Local details and terminologies are neatly used.

For non-geneticists it is informative to know that the so called “paisa mutations” are TRANSMITTED through family generations. But a second and common type are the NEW mutations (de novo), which occur randomly and frequently throughout the entire genome. Both can be either recessive or dominants; usually two or one copy per person, respectively, are needed to cause a genetic disease.

Mauricio Camargo (PhD)(*)

(*) Recently retired professor of Human Genetics, University of Antioquia

Excellent! A really fascinating read.