Against the Stream: The Future of the Federal Clean Water Rule

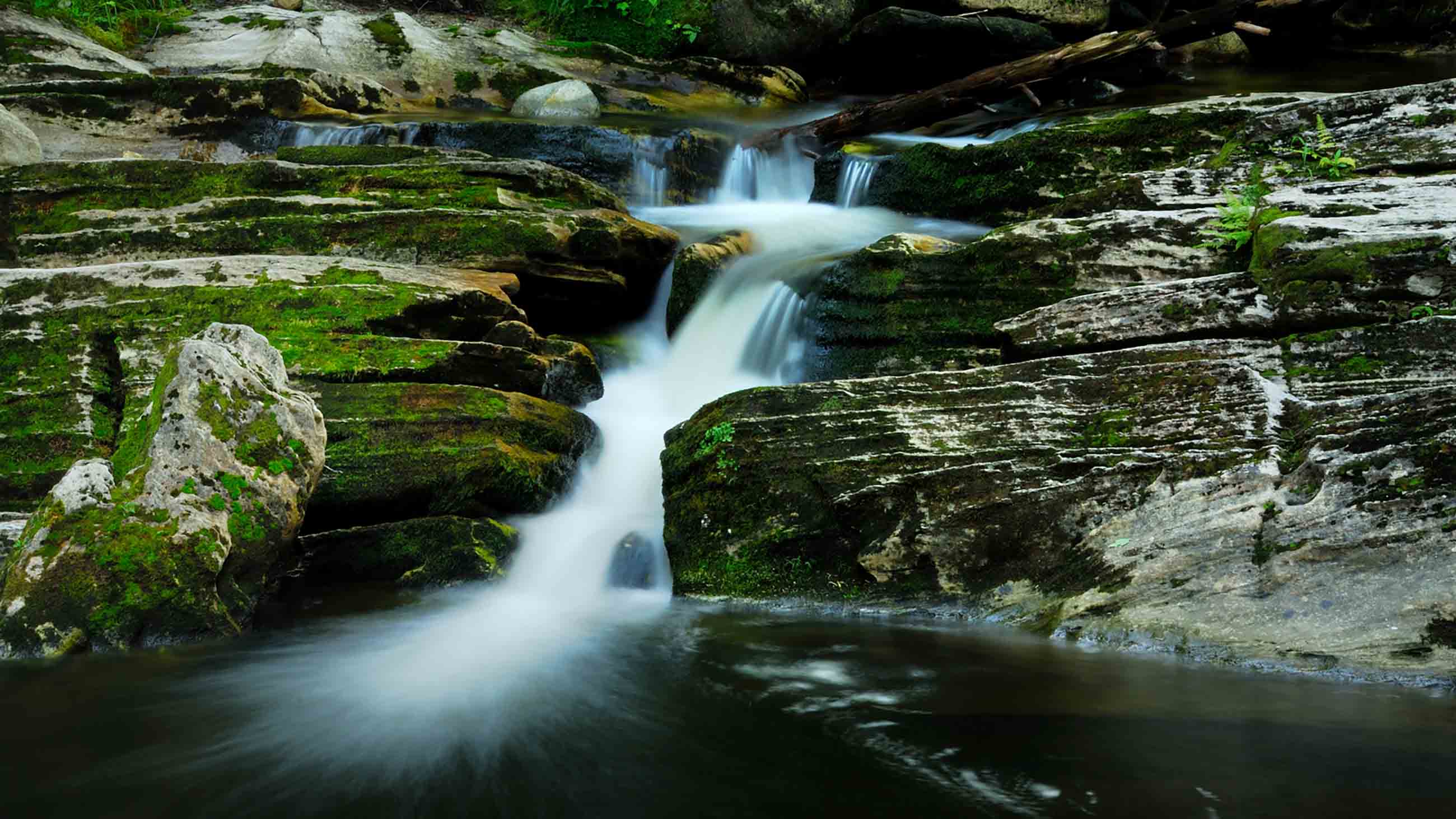

High up in Washington’s Cascade Range, snow feeds the creeks that descend toward the coast, flowing intermittently in summer and gaining strength again the following spring as they coalesce into the Cedar, Snohomish, and Stillaguamish rivers that dump into Puget Sound. These mountainous creeks have a major influence on downstream water quality, and polluting them could jeopardize clean drinking water for much of Seattle’s population, as well as the spawning habitat for the state’s iconic salmon and trout fisheries.

They are among the two million miles of streams and 20 million acres of wetlands across the United States that, as a result of pressure from the administration of President Donald J. Trump and allied Republicans in Congress, are currently at risk of losing federal protection under the 1972 Clean Water Act.

“The waters potentially at risk here include streams that don’t flow year-round, which make up about 59 percent of the stream miles in the continental U.S., and waters nearby,” wrote Jon Devine, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental advocacy group based in New York City, in an email. These streams, Devine said, “contribute to the drinking water supplies of 117 million Americans.”

In June, federal environmental agencies proposed to scrap an Obama-era rule explicitly defining which waters fall under the Act’s jurisdiction. Waters such as rivers, lakes, and coastal seas have always been protected under the law, but whether or not to include streams and wetlands in its purview has been fiercely debated.

Published in 2015, the Clean Water Rule clarified the scope of the Clean Water Act to protect these and other bodies of water, drawing praise from ecologists and most environmental groups and withering attacks from farmers, developers and Congressional critics, including John Boehner, the former House Speaker, who called the rule a “raw and tyrannical power grab” that would put businesses “on the road to a regulatory and economic hell.” Among other things, critics say the rule puts vast amounts of private land under federal control, and defines protected waterways so expansively that development and agriculture would be subjected to onerous and extensive layers of red tape with questionable environmental benefits.

The rule was suspended by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in Boehner’s home state of Ohio only weeks after it became effective, and it has been stuck in litigation ever since. In moving now to kill it off entirely, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers are heeding an executive order issued by President Trump in February, which called for “rescinding or revising” the rule, and returning authority for stream and wetland protection back to the states.

The proposed rollback was officially issued on July 27th, and was granted 30 days of public comment — although a coalition of Democratic Senators have publicly urged EPA administrator Scott Pruitt to extend that period by at least 90 days. Whether that extension will be granted is unknown, but nearly 20,000 comments had been submitted on the contentious proposal as of this week.

Should Pruitt proceed with the plan, it would almost certainly be challenged in court — a predictable outcome, given the stakes. After all, precisely how we define waterways — and whom we deputize to protect them — are questions with far-reaching impacts for just about every American. They entangle everyone from consumers and businesses to farmers and fishermen, and the issue hinges on whether or not state-level oversight could ever be sufficient to protect stream and wetland water quality. It also comes with one unassailable certainty: We know much, much more about the ecological complexity and connectivity of minor streams and wetlands than we did 40 years ago, when national legislation protecting American waters from pollution was first forged.

In an email message, Erin Ryan, a professor of environmental law at Florida State University’s College of Law, in Tallahassee, suggested the impacts of the Trump administration’s executive order, if it were to be realized, would be widespread. “I think it has the potential to create enormous consequences on the ground, especially in parts of the country where state-based regulations are less stringent than federal regulations have been,” she said. “It’s also complicated because many of these local watersheds are nested within larger interstate watersheds, creating spillover consequences across state lines.”

The Clean Water Act was passed in the 1970s after it became evident that the states were failing miserably in their efforts to protect water quality. (Notably, Ohio’s heavily polluted Cuyahoga River caught fire 13 times between 1868 and 1969, causing millions of dollars in damage to bridges and other infrastructure.) The legislation authorized the EPA to regulate pollution discharges into “navigable waters” — that is, waters that can be or are currently used in commerce, collectively known as the “Waters of the United States.”

At the time, the ecological significance of non-navigable waters wasn’t as apparent, but scientists have learned a great deal in the intervening decades. Gillian Davies, an ecological scientist at BSC Group, an engineering and environmental consulting firm in Boston, and until recently the president of the Society of Wetland Scientists, said researchers have since learned that intermittent streams, wetlands, and larger waterbodies connect in many ways, including sometimes sharing hydrological connections underground. Carbon, nutrients, microbes, and pollution often move into navigable waters from non-navigable waters nearby. Davies likened wetland tributaries to capillaries in the body. If you introduce a pollutant into a capillary it can reach a vein and affect organ functioning. And just like kidneys, she explained, wetlands filter toxins, and they also store excess water and release it in dry weather.

When the Supreme Court tried to clarify the Act’s jurisdiction over streams and wetlands, however, it muddied the waters considerably, said Jeanne Christie, executive director of the Association of State Wetland Managers, a non-profit advocacy group in Windham, Maine.

Earlier Supreme Court rulings had protected wetlands if they were immediately adjacent to navigable waters, but left open what do if they were separated by non-navigable creeks or groundwater. It was in the midst of that uncertainty — and despite repeated warnings from the Army Corps — that John Rapanos, a developer from Midland, Michigan, filled 54 acres of wetlands on his property that were connected by ditches and streams to navigable waters lying up to 20 miles away. When the federal government sued, Rapanos vowed a legal fight to the death. His case, Rapanos vs. the United States, was decided by the Supreme Court in 2006, producing a highly-fractured ruling with five different opinions and no majority view.

The influence of the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia looms large in the current debate over the Clean Water Rule.

Visual: Alex Wong/Getty

Taking one extreme position, Antonin Scalia and three other justices argued for limiting the Clean Water Act’s jurisdiction to “relatively permanent, standing, or continuously flowing bodies of water” that are connected to downstream navigable waters, and to wetlands with a “continuous surface connection.” At the other extreme, Anthony Kennedy argued for jurisdiction over streams, wetlands, and non-navigable waterbodies connected by a so-called “significant nexus.” By that, Kennedy was referring to the capacity of these smaller waterbodies to affect the chemical, biological or physical integrity of downstream navigable waters, even when a permanent surface connection between them didn’t exist. The other four justices concluded that waterbodies meeting either the Scalia or Kennedy tests for jurisdiction could be federally protected.

Stephen Samuels, a recently retired attorney with the Justice Department and a leading expert on the Clean Water Act, says the Rapanos decision, which sent to the case back to the lower courts, raised more questions than it answered. For instance: Which test was legally binding? And what do the terms relatively permanent, continuous surface connection, and significant nexus mean?

None of those terms had ever been used in prior regulations. So in that vacuum, “the EPA and the Army Corps were forced to perform case-by-case jurisdictional determinations — tens of thousands — every year,” Samuels wrote in an email. “This was extremely resource intensive, both for the agencies and for the regulated public.”

According to a 2010 New York Times article, the EPA became so burdened by individual assessments after Rapanos that it simply gave up and shelved more than 1,500 of them. The Times reported that “some businesses are declaring the law no longer applies to them,” and that “pollution rates are rising.” (Despite repeated requests, EPA officials declined to comment for this story.)

It was only after developers, farmers and environmental groups began demanding jurisdictional clarity that the EPA and Army Corps set out to enumerate precisely which waterways are covered by the Clean Water Act and which are not. More than a million public comments were submitted to the agencies during this process, which culminated with the Clean Water Rule, a 75-page document skewing towards Kennedy’s opinion in the Rapanos case.

The rule stated that all traditionally navigable waters were jurisdictional, but so were streams and wetlands with a significant hydrological or ecological connection to larger navigable waters, as well as all tributaries characterized by physical indicators of flow, meaning a bed, a bank, and a high-water mark that might be evident even when the tributary itself was dry. Manmade ditches with a significant nexus were covered, with certain exceptions made for ditches on agricultural lands (to avoid regulating irrigation ditches on farms) and for those lining transportation corridors along roads, railways, and airports.

The rule also covered unique and ecologically sensitive waterbodies, such as prairie wetlands, or “potholes” in the West, temporary ponds called vernal pools, and wetland bogs called pocosins. Finally, the rule assigned jurisdiction to any body of water within the area that could be submerged within a 100-year floodplain and is within 1,500 feet of the high-water mark of a navigable waterbody. Waters in that floodplain and that are within 4,000 feet of the high-water mark would be subject to a case-by-case analysis.

ALL WET?

President Trump famously derided the Obama-era Clean Water Rule as regulatory overreach, suggesting that the provision, which his administration is now trying to roll back, would result in federal oversight of “puddles.” While the rule does expand federal environmental protections to small streams and wetlands, it explicitly rules out a variety of waterbodies, including, yes, puddles.

The following are among many features that are not considered to be “waters of the United States” under the Clean Water Act:

* Artificially irrigated areas that would revert to dry land should application of irrigation water to that area cease

* Artificial, constructed lakes or ponds created by excavating and/or diking dry land such as farm and stock watering ponds, irrigation ponds, settling basins, log cleaning ponds, cooling ponds, or fields flooded for rice growing

* Artificial reflecting pools or swimming pools created by excavating and/or diking dry land

* Small ornamental waters created by excavating and/or diking dry land for primarily aesthetic reasons

* Water-filled depressions created in dry land incidental to mining or construction activity, including pits excavated for obtaining fill, sand or gravel that fill with water

* Erosional features, including gullies, rills, and other ephemeral features that do not meet the definition of tributary, non-wetland swales, and lawfully constructed grassed waterways

* Puddles

Source: Federal Register, “Clean Water Rule: Definition of ‘Waters of the United States.’”

The path to the rule was hardly smooth, due in part to the history of tension between the EPA and the Army Corps over differences in jurisdictional responsibility. The EPA took the lead in writing the final draft, shutting out the Army Corps, which leaked internal memos to the press citing problems on several fronts.

Lance Wood, an Army Corps attorney, wrote one of those memos. In it, he argued that in some ways the rule wasn’t protective enough. The 4,000-foot cut-off was arbitrary and lacking in scientific justification, he claimed, and would exclude too many lakes, ponds, and wetlands from jurisdiction. But he added that in other ways the rule had gone too far, since it assigned jurisdiction to what he called “truly isolated waters,” such as prairie potholes, with questionable connections to navigable waters.

Predicting the rule wouldn’t survive judicial review, Wood wrote, “This assertion of CWA jurisdiction over millions of acres of isolated waters may well be seen by the federal courts as regulatory over-reach, which undermines [the rule’s] legal and scientific credibility.”

Critics were quick to pounce. Notably, representatives from the farm lobby complained that the language excluding irrigation ditches was too vague, and they ridiculed the jurisdiction over dry tributaries simply because computer models might reveal prior indicators of flow. According to Don Parrish, senior director for regulatory relations at the American Farm Bureau in Washington, D.C., the only way farmers could be sure they weren’t breaking the law would be to call a government official and say “Please tell me what on my farm you want to regulate.”

That didn’t sit well with farmers who already know the difference between a stream and a ditch on their own land, Parrish said.

The farm lobby’s relentless attacks on the rule infuriated those who say the agencies bent over backwards to assuage its concerns. Samuels, the recently retired Justice Department attorney, said the lobby’s campaign to portray farmers as victims was an exercise in alternative fact-making. The rule retained preferential treatment for farmers, Samuels said, and “actually went one step further by requiring case-by-case determinations of significant nexus for agricultural wetlands that would otherwise be automatically jurisdictional if not used for farming purposes.”

Even so, he said, the farm lobby overreacted and mischaracterized the rule.

President Trump himself mischaracterized the rule by claiming it would regulate “nearly every puddle,” when in fact it explicitly exempted puddles from federal jurisdiction. Meanwhile, opinions differed sharply over how much acreage the rule would add to federal oversight. The EPA’s estimate was 1,500 acres, while the editors of Oklahoma’s largest newspaper, The Oklahoman, claimed that “an estimated 8.1 million miles of supposed rivers and streams will be affected.”

Experts now say the rule’s demise could be imminent, given that President Trump, EPA administrator Scott Pruitt, and the Republican majority in Congress are all united against it. So where does that leave prospects for streams and wetlands?

Repealing the Clean Water Rule is simply a first step toward the Trump administration’s broader goal, which as stated in the executive order is to redefine Waters of the United States according to Scalia’s opinion in the Rapanos case. Environmental groups see that as a worst-case scenario. “It’s impossible to overstate the harm that could result from making more than half of the nation’s waters more vulnerable to pollution and destruction,” said Devine of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

But according to Samuels, efforts to adopt Scalia’s opinion as the law of the land would still face significant legal challenges. No court has ever concluded that the Act’s jurisdiction must be based solely on Scalia’s opinion, he explained. Instead, the courts have leaned more often toward Kennedy’s significant-nexus test, and “if the Trump administration were to attempt a new, narrower definition of Waters of the United States on policy grounds rather than on a revised legal interpretation of Rapanos, it would still face an uphill battle in any future litigation,” Samuels said.

Notably, he added, the Trump administration would have to justify its disregard for research that overwhelmingly demonstrates the substantial ecological connectivity between streams and wetlands and navigable waters.

Should federal protection be reduced, then it would be up to the states to take up the regulatory slack. Chris Wilke, executive director of Puget Soundkeeper, a Seattle-based environmental group, warns that absent sufficient federal oversight, states might fall victim to special-interest pressure to weaken their own protections — a prediction that Samuels agrees with. That could trigger a race to the bottom, both say, wherein states cut back on their environmental rules in a competition to attract industries. For instance, Wisconsin officials recently offered to exempt the Taiwanese company Foxconn from state wetland regulations at the site of a proposed 20 million-square-foot electronics plant in the south of the state.

“This is why we need a strong and protective Clean Water Act that establishes a national baseline,” Wilke wrote in an email.

However, John Kolanz, a partner with Otis, Bedingfield & Peters, a Colorado law firm, who has written extensively on the Clean Water Rule, thinks those fears are overblown. He points out that environmental values have shifted since the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972. “While priorities might differ from state to state, most people understand that racing to the bottom will impair the ability to attract good employers and an educated workforce,” he said. “A recent report shows that outdoor recreation generates $28 billion in consumer spending annually in Colorado. It would not make economic sense for Colorado to let its waters degrade.”

Ironically, developers and farmers who have fought the rule may see little relief if it is repealed, according to Reagan Waskom, director of the Colorado Water Institute at Colorado State University. In passing the rule, the Obama administration had hoped to create greater clarity and reduce the number of case-by-case significant-nexus evaluations, which can drag on for years and consume thousands or even millions of dollars. In one particularly egregious case, Northern Integrated Supply Project, a proposed reservoir and water distribution project in Colorado’s Northern Front Range, has been negotiating its Clean Water Act permit since 2004. More than $18 million has been spent on site investigations so far, and the permit has yet to be granted.

Withdrawing from the Clean Water Rule would put regulation back to where it was in the 1980s, Waskom said, with uncertainty surrounding how we interpret requests for determining jurisdiction. Getting a new rule in place will take a long time, he added. Meanwhile, the Clean Water Act will remain in force, and the agencies will still have to implement the law in accordance with existing standards.

“The regulated community might find itself in an even slower world than it’s in now,” Waskom said.

Charles Schmidt is a recipient of the National Association of Science Writers’ Science in Society Journalism Award. His work has appeared in Science, Nature Biotechnology, Scientific American, Discover Magazine, and the Washington Post, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

This article provides excellent and balanced coverage of a complicated and contentious issue. Unfortunately in today’s world, hyperbole tends to drive the debate on such issues, making appropriate (and lasting) resolution elusive. The upcoming phase 2 rulemaking will have real life consequences for the country. It is a big deal, and there is legitimate concern on both sides. This is also an opportunity to solve a long-standing problem, if we are so inclined. Perhaps one place to start is to recognize that we all live on both ends of the pipe.

Clean water is important to everyone and the Clean Water Act has been important to cleaning up the a great deal of pollution. States have certainly become much more involved in preventing pollution over the past 2-3 decades. So are local governments and many others. Certainly there will be disagreement about what should be protected, who should be responsible, how much is enough and so on. This is a diverse country with deserts, tropical forests, prairies, forests, tundra etc. and it is very, very difficult to write a regulation that anticipates and addresses all this variability. Therefore the more people who are knowledgeable about how we got here and have some thoughts to share about what should happen next, the better! This is a great analysis including some of the diverse perspectives on what’s important going forward. Thank you!.

Clean water is important to everyone and the Clean Water Act has been important to cleaning up the a great deal of pollution. States have certainly become much more involved in preventing pollution over the past 2-3 decades. So are local governments and many others. Certainly there will be disagreement about what should be protected, who should be responsible, how much is enough and so on. This is a diverse country with deserts, tropical forests, prairies, forests, tundra etc. and it is very, very difficult to write a regulation that anticipates and addresses all this variability. Therefore the more people who are knowledgeable about what how we got here and have some thoughts to share about what should happen next, the better! This is a great analysis of how we got here and some of the diverse perspectives on what’s important going forward. Thank you!.

I have been involved in WOTUS development and implementation for several decades, and this is one of the best analyses I’ve read of what’s at stake. After many successes improving the quality of the nation’s waters, we are now at a critical stage, which could determine whether we will maintain or simply drain our swamps and other valuable waters.

.

The Obama regulations say that waters with “connectivity” to one another should be regulated similarly, with absolutely no definition of what “connectivity” means. They were asinine.

.

^Actually this comment is 100% incorrect.

Prior to the Clean Water Rule it is true that the standard was based on connectivity/significant nexus. Basically a scientific test. This was based on the Supreme Court decision in Rapanos. What the Clean Water Rule attempted to do was categorically define which waterways were subject to protection, leaving little doubt as to what was in and what was out.

Here is what is little understood on both sides: THE CLEAN WATER RULE ISSUED BY OBAMA ACTUALLY REDUCED THE NUMBER OF WATERWAYS PROTECTED BY THE CLEAN WATER ACT. Read that again if you must. If you need to verify that statement read the preamble of the Rule. It’s says just as much.

The only possible explanation for railing against the Clean Water Rule is you either: A) dislike the fact that important waterways are no longer protected under this Obama-era Rule, B) you are ignorant of this and just hate Obama and the EPA in general, or C) you want to do away with the Rule and issue another one that guts protections for thousands of miles waterways all across the country that have been protected for the last 45 years, opening the way rampant development and destruction and bringing an enormous cost in terms of economic loss, human health and the survival of fish and other aquatic species.

The latter is what Trump and Pruitt and their special interest cronies are actually trying to do.

We need to protect our water resources.

Only when the last buffalo is killed, and the last stream poisoned, will the rich realize that you cannot eat money. The EPA has been infiltrated by natural gas and coal personnel as a result of the current administration, and they would gladly trade the drinking water of a bunch of people they do not know and will never meet, if it meant they could earn a few extra million dollars. Just ask the citizens of Flint Michigan how they feel about people playing politics with their drinking water to earn some easy money. I promise you this, if this happens, and a second Flint occurs where citizens cannot access clean drinking water for an extended period, this administration will be chased out of office so fast it would make Donald’s hair piece spin. Do the right thing.