Boxed in: The Struggles of Gaza’s Technology Entrepreneurs

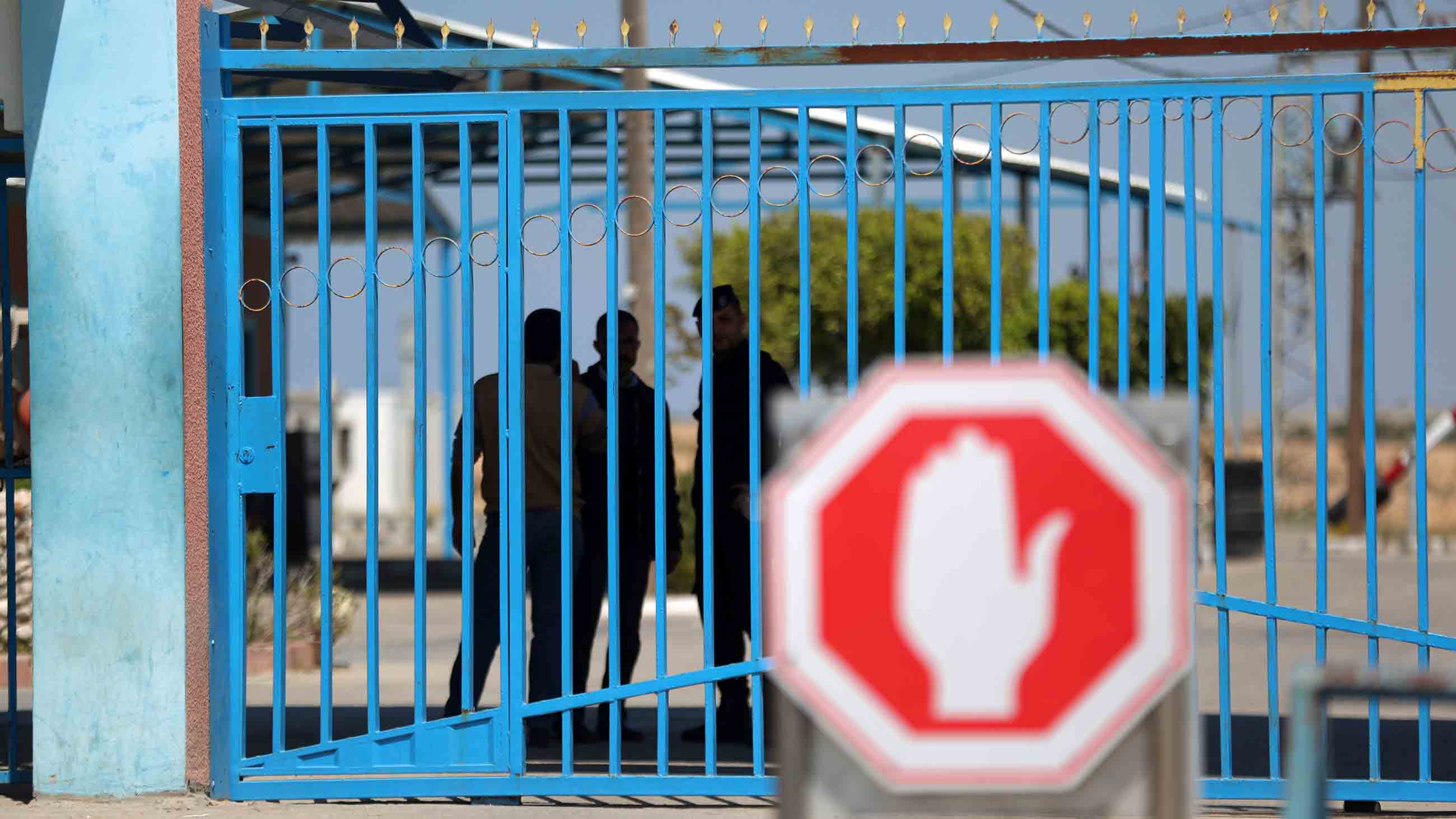

In January 2017, Bassma Ali, the cofounder and business manager of GGateway, an information technology company based in Gaza, was invited to Laos to take part in three weeks of training offered by Digital Divide Data, an organization that provides career development opportunities for underserved communities. On the day of her departure from Gaza — the embattled 25-mile-long strip of land currently under a decade-long blockade by Israel and Egypt — Ali had to pass through three checkpoints to reach Israel. First, there was Arba’a-Arba’a (Arabic for “Four-Four”), controlled by Hamas, the militant Islamic Palestinian group governing Gaza; second, Khamsa-Khamsa (“Five-Five”), manned by Fatah, the secular Palestinian national movement; and finally, the Erez border crossing, overseen by the Israel Defense Forces.

Even though Ali had applied two months earlier for an Israeli permit to leave Gaza with the help of a representative from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), her permit only reached her at Khamsa-Khamsa at 2:57 p.m., just three minutes before the closure of Erez. “I was running to reach the Israeli gate” half a mile away, Ali recalls. “When they closed the gate, I was in tears.”

She eventually managed to cross the border later that day after an UNRWA aide intervened, but her ordeal didn’t end there. She traveled by taxi through Israel to the West Bank city of Jericho, and crossed into Jordan after navigating three more checkpoints: Palestinian, Israeli, and Jordanian. From the Jordanian capital of Amman, she took three connecting flights to Laos, and finally arrived in the capital, Vientiane, four days after she left Gaza. “Every single border is dehumanizing you,” Ali says.

“When I arrived in Laos, I was almost dead,” she adds.

For the 1.8 million Palestinians living in Gaza, freedom of movement is a routine challenge. And for technology entrepreneurs and business owners whose livelihoods depend on interaction with the outside world, that challenge is especially daunting. “Living in Gaza is like facing a wall, all the time,” says Ali.

Tight restrictions on foreign travel are among many obstacles faced by the roughly 200 companies in Gaza’s burgeoning information and communications technology (ICT) sector. All of them have endured downturns and rebounds through intermittent war with Israel, daily electricity outages, and constraints on the importation of communications equipment. The overall unemployment rate in Gaza stands at 44 percent and residents also must deal with health risks like an acute shortage of safe drinking water and treated sewage.

Despite the odds, Ali and computer engineer Rasha Abu-Safieh, GGateway’s cofounder and social mission manager, are among the entrepreneurs who are busy founding startups, designing websites, coding, and even competing in hackathons. Among its services, the nonprofit GGateway provides software outsourcing services to a variety of organizations, including U.N. Women and U.N. Habitat, and offers training to university graduates, as well as a fully equipped workspace for freelancers. Another nonprofit, Gaza Sky Geeks, founded in 2011 in partnership with Google and the nongovernmental organization Mercy Corps, has provided support for more than 50 startups over the past five years. PICTI, Palestine’s Information and Communications Technology Incubator, offers training as well as legal and financial support to technology startups in Gaza. And one small Gaza outfit, Mutaurin (Arabic for The Developers), runs on solar power.

Gaza’s ICT industry exports software products worth an estimated $10 million to $30 million per year, according to the Palestinian Information Technology Association of Companies. That is possible because selling software on the internet sidesteps the blockade imposed on Gaza by Israel and Egypt since 2007, when Hamas took power in Gaza.

Israel, along with the United States, considers Hamas a terrorist organization and tightly restricts the entry of products into Gaza that appear on its “dual use” list — items, including communications equipment, that are, according to the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “liable to be used, side by side with their civilian purposes, for the development, production, installation, or enhancement of military capabilities and terrorist capabilities.” Israel also does not permit Gaza to operate an airport, and travel into Israel from Gaza via Erez (the Rafah exit into Egypt is opened intermittently) is limited to a small number of business people, medical patients in need of life-saving treatment, and “exceptional humanitarian cases.”

“You have an entire generation of young people now, who are savvy, who are very connected into the internet, and know exactly what’s going on outside Gaza,” says Ryan Sturgill, the Chicago-born director of Gaza Sky Geeks. “But they have no ability to leave Gaza.” Several requests for comment from COGAT, the Israeli Ministry of Defense body that coordinates with the territory, went unanswered.

With funding from Google for Startups, along with other donors, Gaza Sky Geeks provides a shared workspace in Gaza City (and another in the southern Gazan city of Khan Yunis) to freelancers and the public, with the goal of building a “supportive, inclusive, vibrant” tech community, says Sturgill, who joined the organization in 2015.

Gaza Sky Geeks runs a six-month immersive software engineering program to teach people how to code, as well as a freelancing academy for anyone with skills with which they can earn money online, such as graphic design or translation. The organization is also a startup accelerator, helping founders to launch products online and gain traction from users, and preparing them to pitch to angel investors and venture capitalists to secure their first commercial capital.

Some of those startups get their initial push through a new program called GeeXelerator, says Iyad Altahrawi, incubation and acceleration program manager for Gaza Sky Geeks. The Gaza-born Altahrawi says he turned down three job offers in Germany, where he was working and studying, to take up his current position in 2017. “I did not really hesitate,” Altahrawi says.

“Friends and family are an important factor, but to be honest I wouldn’t go back to Gaza to work anywhere else other than Gaza Sky Geeks,” he added. Altahrawi said he wanted to be part of an organization that’s driving change.

In May 2018, Altahrawi brought 34 teams into the GeeXelerator program, where they received mentorship, coaching, and access to services like mobile app-building. The top five finalists went on a road trip to meet investors in Jordan, Egypt, Turkey, Bahrain, Germany, and the United Arab Emirates. Some of the winning startups include Lavender, which sells Arabic-language customized website themes; Araboost, a platform that enables social media influencers to connect with corporate brands on marketing campaigns; and Hera, which helps couples compare deals from wedding vendors in Palestine.

But such travel opportunities aren’t typically available to tech entrepreneurs in Gaza, Sturgill notes. For the most part, they can’t meet clients outside Gaza, and are unable to earn professional experience elsewhere. The inability to leave, and lack of interaction with developers who have expertise in cutting-edge technologies, “has had a stunting effect on a whole generation of young people who want to work in tech,” Sturgill says.

“Both my colleagues and the startups that we work with, they’re constantly getting invited to speak at conferences, or meet with investors outside, or they get scholarships, but they can’t get a permit to leave Gaza, because they are deemed a security threat,” he added.

“Gazans are the most resilient people I’ve ever worked with,” he says. But, “there may be subconscious damage that goes with having these opportunities and dreams continually quashed.”

As for Ali, her 2017 trip to Laos proved to be successful for GGateway’s business: She set up a strategic alliance with Digital Divide Data to create Arabic language digitization services for the organization and agreements to subcontract work for the group. GGateway also received a $3 million grant from the World Bank last May to fund its business development and marketing. That grant was the fruit of a July 2017 pitch, arranged for Ali by a friend of a friend, to a World Bank economic development delegation visiting Ramallah, the de facto administrative capital of the Palestinian National Authority in the West Bank. “I just showed up in the hotel where they are,” Ali laughs. “I had a permit at that time, and I remember I was two months’ pregnant, and I said, O.K., if I didn’t do it … it won’t happen.” She gave a 10-minute presentation on GGateway, “and they kept asking me questions for four hours.”

The grant, however, came after years of struggle. Abu-Safieh and Ali launched GGateway in 2013 with a pilot project for UNRWA, but that came to a grinding halt in July 2014 with the start of the “50 Days” conflict with Israel, in which more than 2,100 Palestinians — including 1,500 civilians, according to the U.N. — in Gaza were killed. (Sixty-six Israeli soldiers were killed in the fighting, and six Israeli civilians and one Thai national were killed by Hamas missile attacks on Israel.) Among those killed was a close friend of Abu-Safieh’s, who died along with her entire family, including her two children, when her apartment block was bombed.

Soon after the war ended in August 2014, the GGateway team met with a psychologist, “and all the people in the room were crying for three hours,” Abu-Safieh says. But they managed to regroup, and in 2015 the Korea International Cooperation Agency gave GGateway a $1.3-million funding grant.

Both GGateway and Gaza Sky Geeks actively seek out and promote women; GGateway maintains a balanced female-male gender balance among the people they recruit, and 42 percent of Gaza Sky Geeks’ community members are women, notes Nadia Abu Shaban, its startup program coordinator.

“We have 1,000 graduates in the ICT sector in Gaza every year, and 50 to 60 percent of them are women,” Ali explains. “Ninety-two percent of them are unemployed. But for the males, it’s 65 to 70 percent are unemployed.”

The representation of women in science, engineering, and mathematics in Gaza’s universities is high, says Sturgill of Gaza Sky Geeks. Unfortunately, he adds, women tend not to pursue careers in software development because of cultural pressure on women to marry after graduation and start a family.

As a result, “it’s really important to have events that empower women,” says Abu Shaban, the startup program coordinator. In October, she helped organize a “Code4Hope” hackathon to highlight Breast Cancer Awareness Month. In Gaza, Abu Shaban says, there is a general lack of awareness of breast cancer risks and insufficient access to breast cancer exams. Over the course of one day, 13 teams coded tech solutions to some of these problems. The winning team was awarded $1,000 for an app called “Feel Me” that offers information about breast cancer and provides notifications about medication to those who are battling the disease. Other teams coded apps to remind women to go for mammograms, and others to connect survivors and encourage them to share their stories.

“All of the women enjoyed it, because we changed everything into a very social place,” Abu Shaban recalls. “We made the place ‘pinky.’”

But tech companies can only thrive with outside contact — and with a reliable supply of electricity. Most use generators to cope with intermittent electricity outages, which at times in the past year have extended to up to 20 hours a day. Khalil Salim and Reem al-Aweiti, the owners of Mutaurin (The Developers), installed a $12,000 solar energy system in their offices with the aid of a grant from USAID, which promotes development and democracy abroad.

Looking beyond Gaza, most of The Developers’ business — software development, web development, video montage design — comes from companies in Saudi Arabia and the West Bank. And Gaza Sky Geeks recently opened a new coding academy in Hebron in the West Bank, training 13 students to pursue careers as software developers.

GGateway is also looking to expand. With the aid of the World Bank grant, Ali and Abu-Safieh are planning to open an office elsewhere (possibly in Amman) for marketing, sales, and business development, while keeping their main headquarters inside Gaza. “Until now, I have fundraised and signed business contracts for around $4 million, and still I’m invisible,” says Ali.

Despite the conflict that most foreigners see unfolding on television, “we are not all Hamas, we are not all armed conflict, we are not all Jihad, we are not all ISIS,” Ali says. “There are people here, and a community, and what they want at the end of the day is raising their children, and peace.”

They are just trying to make life in Gaza possible, Ali said.

“That’s why we keep moving.”

Josie Glausiusz is a journalist who writes about science and the environment for magazines including Nature, National Geographic, Scientific American, Aeon, and The American Scholar. She is the author of “Buzz: The Intimate Bond Between Humans and Insects.” Follow her on Twitter @josiegz.

Update: A previous version of this piece described Gaza Sky Geeks as a company. It is a non-profit organization.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

This article really should not make people angry or lose their patience with Palestinians. Even the most die hard supporter of the right of Israel to exist by guaranteeing its security through force and power, can’t help but be inspired by the resilience and sheer persistence of Palestinians, who are quite literally powerless.

Entrepreneurship in Gaza is emerging as one of the most democratic forms of non-violent resistance, and enablers for people in pursuit of their human rights. This article swims in that narrative which frankly motivates, engages and involves many more people than those involved in violence and other forms of political struggle.

Long after Hamas has laid down its weapons, it will be this community of inspirational leaders, that have what it takes to build a state or whatever. To discount these efforts or actually choose to discount them is tantamount to supporting the violence and the military mentality.

The response that just essentially says, “it’s your own fault, you get what you deserve” serves no one and nothing, particularly in the context of this story. No progress, no bridges, no future vision – no solution…when there is only defensive and collectively judgmental commentary, and ultimately dismissal, in response to the stories of challenges individuals are facing daily, on a human level — when you cannot even listen to a story of hardship without empathy, well — then, YOU also bear shared responsibility for continuing to promote an atmosphere where NO PROGRESS is possible.

In 2006, the People of Gaza, of THEIR OWN FREE WILL, declared open war on Israel by electing Hamas as their government. The volunteered for this treatment with both eyes open.

people from gaza should leave gaza and go to egypt – which was their country before the war ’67…

if HAMAS would have stopped their neverending attacks on israel after the withdrawal of all israeli settlers and troops and invested all their aid/finances/manpower and intelligence in PEACEFUL enterprises, gaza would be one of the economic miracles in the middle east – like dubai or abu dhabi.

the world is tited by neverending stupid suicidal religious/ethnical war and strife betwenn palestinians and israelis. the simples way to overcome would be: each arab man marries an israli woman and each israeli marries an arab woman – so the war would be inside their four walls at home :))

I got more than 3 job offers to working in leading companies in US but can’t travel anywhere else gaza