Bite Marks and Bullet Holes: The Folly of Police Forensics

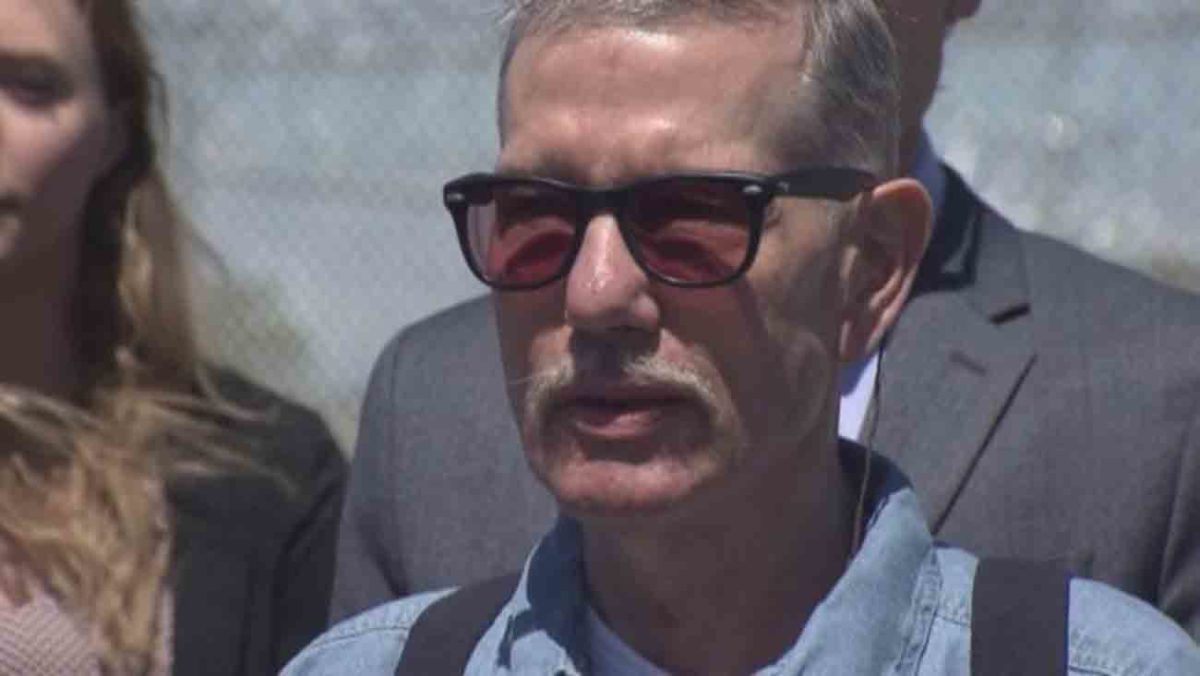

Keith Harward spent more than three decades in prison on the presumed strength of forensic dentistry. No fewer than six forensic dentists testified that his teeth matched a bite mark on a 1982 victim of rape and murder. But in April of last year, after serving more than 33 years in a Virginia penitentiary, new DNA evidence prompted the state Supreme Court to make official what Harward knew all along: He was innocent, and the teeth mark analysis was unequivocally, tragically wrong.

Keith Harward was released from prison at age 60, after spending more than half of his life behind bars.

Visual: The Innocence Project

“Bite mark evidence is what the whole case hinged on and ultimately had me convicted,” Harward said.

“But,” he added, “this stuff is just guesswork.”

Today, many forensic scientists would agree — and they’d say the same, or nearly so, about a menagerie of other techniques that are used to convict people of crimes, from handwriting analysis to tire track comparisons. And while some techniques fare better than others, everything short of DNA analysis has been shown to be widely variable in reliability, with much hinging on forensic practitioners with widely varying approaches and expertise.

It was with this in mind that many forensic scientists expressed dismay that the administration of Donald J. Trump had decided — nearly one year to the day after Harward’s bittersweet exoneration in Virginia — to disband the National Commission on Forensic Science. Established just four years ago by the Department of Justice, in partnership with the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the commission’s goal was “to enhance the practice and improve the reliability of forensic science.”

“We want forensic science to actually be scientific,” said Sunita Sah, a Cornell University behavioral scientist who served on the commission. “It’s got to be valid science, which means it’s got to be reliable, it’s got to be robust. The stakes are very high when you’re using forensic science in court to convict people.”

With the removal of this new and essential channel for forensic science reform, experts now fear that the imperfect — and by that count, potentially unjust — status quo will prevail. That status quo, they say, has for too long placed a burden on untrained judges and juries to figure out what to make of forensic science presented in the courtroom, with the very real risk that they will be swayed by misleading evidence, and with the lives of thousands of defendants like Harward hanging in the balance.

Efforts to improve the situation have a long history. In the landmark 1993 case of Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that judges have a responsibility as the gatekeepers of evidence to ensure that “all scientific testimony or evidence admitted is not only relevant, but reliable.” It also described factors involved in assessing the admissibility of evidence, including whether a forensic technique successfully withstands testing and peer review, whether it has a known error rate, whether standards and protocols have been developed, and whether it is generally accepted in the scientific community.

Those were lofty goals, but since then, the Innocence Project, a non-profit legal organization based in New York that helps wrongfully convicted people, has used DNA evidence to secure 350 exonerations of people convicted of crimes they did not commit. In the majority of these cases, the conviction turned on faulty eyewitness testimony, which itself has been shown to be routinely unreliable. But nearly half of the cases at least partly hinged on some presentation of forensic science — much of which, some scientists suggest, has little research behind it.

“Bite marks is the obvious example,” said Suzanne Bell, a forensic chemist at West Virginia University in Morgantown and another former commissioner. “It’s inconceivable to most of us as to how this stuff even continues to be admitted. It has no scientific basis.”

Other kinds of forensics, like hair and fiber analysis, tool marks, firearms and ballistics, and voice comparisons, are considered more reliable, but these need to be thoroughly assessed to develop validated standards, Bell and others argue. Fingerprint comparisons, a traditional forensic tool, are moving forward, but a 2011 study highlighted the need for more standardization and training. And even DNA analysis doesn’t have an error rate of zero.

In response to growing questions about the reliability of the various forensic techniques being used to convict Americans of crimes, Congress ordered the National Academy of Sciences to study the problem, leading to a major report in 2009. That report came to the damning conclusion that, aside from DNA, “no forensic method has been rigorously shown to have the capacity to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connection between evidence and a specific individual.” It also pointed out that judges and lawyers have insufficient training in scientific methodology, and it argued that police and prosecutors have too much control over crime labs, creating conflicts of interest.

This report eventually gave rise to the Department of Justice’s forensic science commission four years later. The advisory panel produced 20 documents containing recommendations made to the Attorney General during its short tenure — not just about forensic science methods but also how attorneys present evidence. The panel managed to eventually make an impact, as its recommendations trickled down to prosecutors. For example, the DOJ directed forensic examiners to dispense with the expression “reasonable scientific certainty” in their reports and testimony. Such a phrase, often uttered without context in court, can be misleading to both judges and juries. It also required that federal prosecutors use only accredited crime labs whenever possible by 2020.

But their work had really just begun when Attorney General Jeff Sessions, a former prosecutor, terminated its charter, and its members are now lamenting its loss. “Without the commission, I don’t see how we’ll solve these problems,” Bell said. “Science needs to be independent of the prosecutorial side, as well as defense.”

Even more worrying, scientists suggest: Sessions has announced plans for an internal, DOJ task force whose job it will be to make recommendations to advance forensic science.

This is just “the fox guarding the henhouse,” said Thomas Albright, a neuroscientist at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, who also served on the commission. He and others suggest that in practice, little will change with respect to forensic science in the courtroom in the foreseeable future.

That’s because while both prosecutors and defense attorneys want to win their cases, prosecutors have often been far more willing to have their experts play fast and loose with scientific evidence, said David Faigman, law professor at University of California, Hastings. That’s a fundamental injustice, Faigman suggested, when the lives of the accused hang in the balance, and it’s also unfair to the judges and juries weighing their fates. “They fall for Sherlock Holmes syndrome,” Faigman said. “They don’t need to provide a wall of proof, just bricks in a reliable fashion.”

Harward echoed those concerns. “The juries have to believe them because the court approved them as experts and allowed them to testify,” he said.

“But,” he added, “there’s nothing to object to because you’ve got only one side.”

The field is only going to get more complicated. Brain scans and new forms of genetic information are increasingly making their way into courtrooms, while government regulators — already lagging — are struggling to keep up. Other groups dedicated to standardizing and improving forensic science used in the courtroom, including the Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science at NIST, could provide many of the same functions that the shuttered national commission did, but funding for such efforts is far from certain. For now, the OSAC’s funding, which comes from the Department of Justice, is secured until the end fiscal year.

These committees do not make policy recommendations like the commission did, but they do examine 25 areas of forensic science in detail and publish their standards online. Many people in the forensic science, legal, and law enforcement communities are aware of their work, wrote John Paul Jones II, Associate Director of OSAC Affairs, in a statement. But their standards carry much less weight than directives from the Attorney General’s office, and lawyers and forensic practitioners do not have to abide by them.

The DOJ could make local and state grant funding contingent on adopting these standards, or groups that provide accreditation to crime labs could require adoption of OSAC standards as part of that process, said Matthew Gamette, president-elect of the American Society of Crime Lab Directors.

The DOJ could also make a priority of providing more training opportunities to lawyers and judges about the subtleties, uncertainties, and latest developments of forensic science — but no such efforts are currently underway, according to Judge Christopher Plourd of the Imperial County Superior Court in El Centro, California and chairman of the legal resource OSAC committee.

Until that happens, there will continue to be Keith Harwards who are wrongfully convicted of crimes they didn’t commit, and very often on the basis of forensic “science” with little meaningful research to back it up.

“Good forensic science convicts the guilty,” Plourd said, “and protects the innocent.”

Ramin Skibba is an astrophysicist turned science writer and freelance journalist who is based in San Diego. He has written for Newsweek, Slate, Scientific American, Nature, Science, among other publications. He can be reached on Twitter at @raminskibba.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

As a former scientist, you should know not to write about matters about which you know nothing. OSAC is a creation of the racist, anti-scientific DEA which has instigated the wrongful convictions of hundreds of thousands of individuals, a disproportionate number of whom were blacks, and continues to do so. The first so-called scientific standard created by OSAC was ASTM Standard E2329 which claimed to identify controlled substances in seized samples with “no uncertainty”. Does that sound like science? The standard is applied around the world. Current and former DEA analysts including Joseph Bono, Heather Hartshorn, James Malone, Richard Fox, the late Dr Jay Siegel, , et al attest to infallibility in court under oath with regards to their tests as well as their performances. NIST/OSAC and ASTM now churn out standards and protocols for all forensic disciplines solely by consensus. Does that sound like science? If you have a few days, I’ll continue. BTW, you can count on two, maybe one, hand the number of blacks in these powerful organizations. Not to mention, that ASTM has made tens of millions selling these bogus standards and when I inquired about this, its VP/GC Thomas O’Brien took umbrage then invited me to join ASTM.