Navigating a Sea of Superlatives in Pursuit of the Asian Carp

Rebekah Anderson, a biologist with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, had just dropped her phone in the water. There was no real chance of recovering it, but she and Ronnie Brown were peering down, wondering if it could be salvaged, when Brown saw a fish laying in their net close to the surface.

“Is that an Asian carp?” Anderson remembers him asking. Her mind raced in response. “Oh my gosh — that’s an Asian carp,” she recalls thinking. “Where are we? This is a really big deal.”

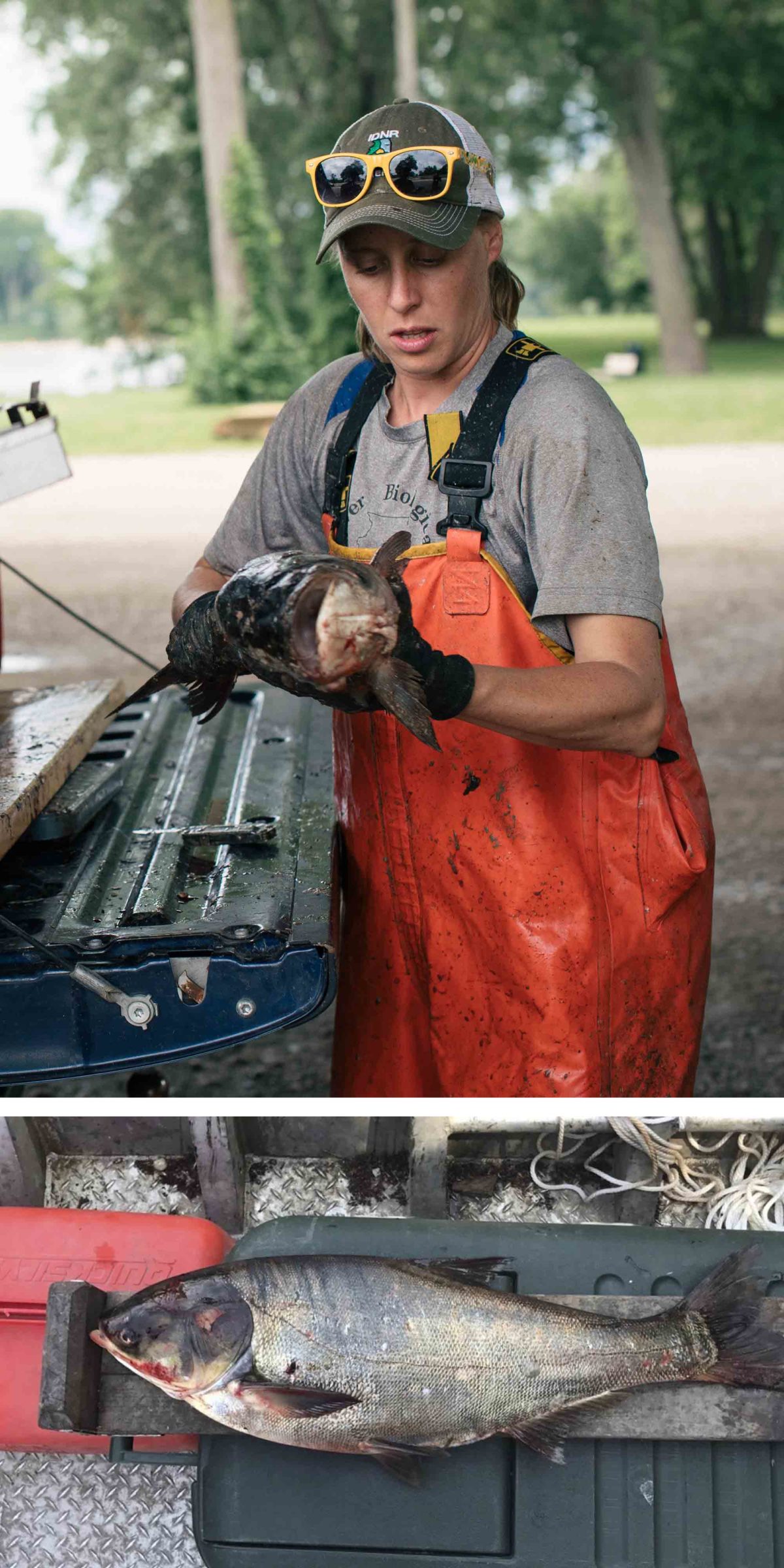

Top: Rebekah Anderson, a biologist with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, surveys a carp earlier this month. Below: The carp she captured last summer above electric barriers designed to keep the invasive species back.

Visual: Alyssa Schukar for Undark (Anderson); IDNR (carp)

They hauled the fish aboard and put it on ice.

It was a variety of Asian carp known as Hypophthalmichthys molitrix, or the silver carp, and both Anderson and Brown, a commercial fisherman, knew that the species was not supposed to be there in the Little Calumet River, nine miles from Lake Michigan. An electric barrier system downstream was supposed to be impassable, arresting any carp swimming north. Dozens of miles below the barriers, the IDNR’s own monitoring showed that the Asian carp population was not advancing. A fisherman contracted by the IDNR had fished this spot the week before and caught nothing unexpected. But now the second Asian carp ever found above the barriers was in their boat. (The first had been caught a full seven years prior — also by Brown.)

Anderson was frantic, but there is a rigid protocol for finding Asian carp in these waters, and she followed it: Stay with the fish, take pictures, get coordinates, make phone calls. It was 9:44 am, Thursday, June 22, 2017.

One of the first people Anderson called was Kevin Irons, who manages IDNR’s Aquaculture and Aquatic Nuisance Species Program. Irons received the news calmly, hung up, and called the conservation police to arrange for them to pick up the fish. He wanted make sure the chain of custody was documented and unbroken. “We don’t want the fish to disappear,” he said later. “We don’t want to be accused of switching fish.” Irons knew immediately that this eight-pound carp had tremendous power. It could be used to call for hundreds of millions of dollars in government spending, or to invalidate hundreds of millions already spent. It could signal an ecological and economic disaster for the Great Lakes and the eight U.S. states and one Canadian province that surround them, or it could be an insignificant aberration.

Such a consequential fish needed exacting stewardship.

In the contentious and often fractious discussions over what to do about Asian carp, facts and science are often distorted, and sometimes ignored completely. Indeed, the only thing all sides seem to agree on is that they should not get into Lake Michigan — but how much prevention is enough, at what cost, and whether the fish would even be able to live in the lake — all of these questions remain up for debate. Most media coverage of the subject has “a desired outcome or opinion or direction… generally leading towards one way — towards the inflammatory, the fear” said Irons.

As it stands, a vast amount of money is either being spent or requested for a battery of new and ongoing defenses, from fortified locks with sound cannons and additional electrical barriers ($275 million), taxpayer subsidized fishing ($1 million per year), and even the wholesale and permanent separation of the Great Lakes from the inland rivers ($3 to $10 billion). Some critics say this is all overkill. Others say no amount of caution is too much. So it’s no surprise that Anderson and Brown’s fish inspired two diametrically opposed refrains, each adopted by different groups based on their own vested interests. One side saw the fish as evidence that “Asian carp are almost in Lake Michigan.” The other side pointed to the same fish as a clear indication that “Asian carp still aren’t anywhere near Lake Michigan.”

Both refrains are based on data generated by Irons’ team, and neither are really accurate.

It’s the jumping that made silver carp famous. The fish react to sound, especially the whine of an outboard motor. (Of the various Asian carp species, silver carp are the only ones that jump.) Irons and his colleague Matt O’Hara filmed and posted some of the first carp-jumping videos. The absurd scenes — a carpet of fish seeming to fly out of the water, many apparently aimed at the heads of unsuspecting boaters — spread online with rapidity befitting a fish that can broadcast its eggs by the millions.

It’s the jumping that caused Asian carp — specifically silver carp, which are the only species that display the behavior — to capture the public’s attention.

Most of the funding for IDNR’s carp monitoring and harvesting program comes from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which, ironically, approved of and paid for some of the first Asian carp imported to the United States. (The fish are native from southern China to eastern Russia.) In the 1960s and 1970s, various state agencies, with support from the EPA and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, brought Asian carp over to see if the planktivores — bighead and silver carp — could provide a non-chemical, environmentally friendly way to remove algae from wastewater treatment ponds.

The initial vector of escape into the wild seems to be Mississippi-connected ponds stocked by the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, but Alabama’s Auburn University and the Illinois Natural History Survey (where research that led to Kevin Irons’ fishing program began) also worked with Asian carp early on. Once in the Mississippi, the foreign fish could, in theory, go almost anywhere — from the Gulf of Mexico inland as far as Minnesota, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania, and out through the five Great Lakes to the North Atlantic — because most of the country’s major water bodies were connected to facilitate transportation.

There are 18 other potential points of entry where a carp-laden stream might mingle with the Great Lakes. The most probable is near Ft. Wayne, Indiana, but so far the fish seem particularly fond of the Illinois River, which joins the Mississippi River near St. Louis and stretches northeastward, splintering into myriad tributaries and engineered canals with various names and a few narrow fingers that reach the shores of Lake Michigan, including the Little Calumet River where Anderson and Brown’s specimen was found.

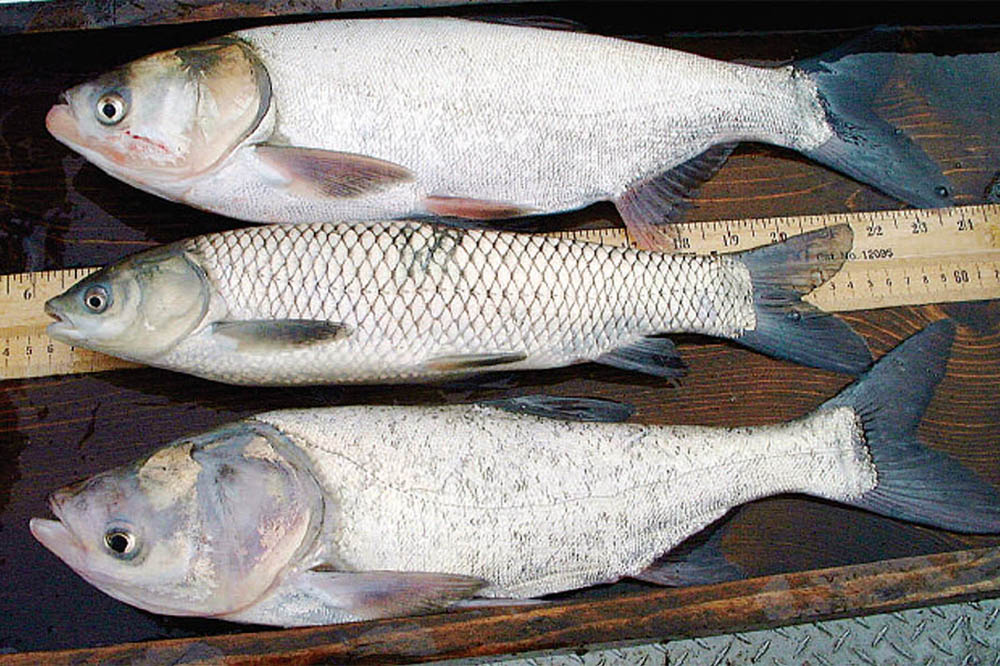

Often hidden in the headlines is the fact that, of the four species of Asian carp that are of most concern for the Great Lakes, grass carp have already been found in three of them, including Lake Michigan. They’re a threat, but perceived by many to be a lesser one because they eat only plants. Black carp, which feed primarily on mollusks, have been tiptoeing into new territory and raising fears as well. But it’s the bighead and silver carp that have caused the most alarm. They eat plankton, the microscopic organisms at the bottom of the riverine food chain. They are efficient feeders, growing quickly and reproducing voluminously. In the U.S., the adult fish have no natural predators. As their numbers increased, silver and bighead carp ate plankton that would have fed native fish. Though other factors may have also played a role, lower numbers of gizzard shad, big-mouthed buffalo, large-mouth bass, crappie, blue gill, and catfish in the Illinois River correlated with the Asian carp boom.

By the time authorities realized the scope of the invasion, the rivers were already infested, and efforts have focused instead on protecting the Great Lakes. The fear is that the invaders will out-compete native fish in the lakes, leading to the decline of a commercial and sport fishery said to be worth at least $7 billion. That threat has made the Asian carp one of the most feared and reviled fish in America — the subject of more headlines, scientific research, and public and private debate than, in all likelihood, any other fish. Carp questions and demands frequently leave the mouths and desks of governors, senators, representatives, and colonels, and a net of superlatives surround the fish, which are considered “shocking,” “menacing,” “voracious,” and a “threat” with the potential to “decimate” and an “enemy” to “battle.”

▲ Researchers have been monitoring carp in the Illinois River since the 1990s, when a day of gill netting would come up with one or two. Beginning around the year 2000, their nets started coming up with hundreds.

Video by IDNR

In spite of these fearsome adjectives, the leading edge of the bighead and silver carp population, the last place where the adult fish can reliably be found en route to Lake Michigan, has remained mysteriously static since 1991. During the 11 years between then and when the first of four electric barriers was built on the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, a manmade conduit that connects through a channel to the Calumet at the western edge of the city, only three locks and three dams stood between the carp and the lake.

A lock is like a water elevator, allowing boats to travel up or down the height of the dam by floating in an enclosed chamber of water. Traveling upstream from the leading edge to the lake, the first dam a carp would encounter is Brandon Road, about 50 miles southwest of Lake Michigan, in Joliet, Illinois. It is 34 feet high. The second, five miles further upstream at Lockport, is about 39 feet. It would be impossible to swim up either one, but it would be easy, at least theoretically, for any fish to swim with a boat into the chamber, wait for it to fill, and swim out on the other side. From there, an Asian carp could navigate any one of several splintering tributaries and manmade channels that circulate through southern Chicago. It would encounter a final lock at the end of the Chicago or Calumet rivers — and from there could enter Lake Michigan. And yet so far, the bighead and silver carp population has stayed put.

Habitat might be one reason. Above the leading edge, the waterway narrows, leaving behind the broad stretches of floodplain and backwater lakes that Asian carp prefer. Just below this point, the Kankakee River meets the Des Plaines to form the Illinois, resulting in a much broader, island-filled, and plankton-rich stream. The breeding population is even further downstream, many river miles and lock and dams away, below Starved Rock State Park. (Because carp eggs need to flow for 24 to 48 hours to remain viable, the constricted conditions upstream are not suitable.)

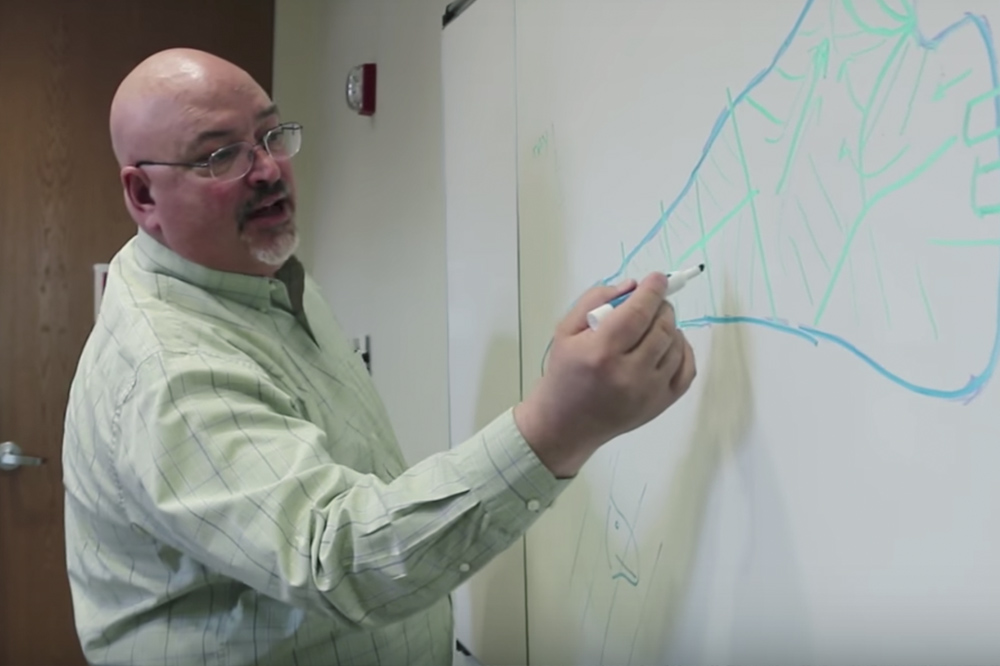

Jim Duncker, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, thinks that chemical and pharmaceutical pollution in the Chicago-area waterways might be contributing to keeping the Asian carp at bay.

Visual: Alyssa Schukar for Undark

Another theory has to do with sewage. The Chicago and Sanitary and Ship Canal was built in 1900 to divert Chicago’s wastewater — tannery spoils, dead animals, human waste, and more — away from Lake Michigan, where the city has always drawn its drinking water. Formerly, the Chicago and Calumet rivers flowed into the lake, while the Des Plaines flowed south. At great effort and cost, with steam power and mules, a canal was carved through the dolomite bedrock to divert the polluted urban rivers away from the city’s drinking water and into the Mississippi-bound Des Plaines. With the divide breached, water from the lakefront and points inland flowed sluggishly south. Aquatic life, ships, and later towboats and other vessels could then travel freely from river to lake and back again.

Around 70 percent of the volume of the Sanitary and Ship Canal remains treated wastewater, coming from sinks, toilets, showers, or from rain falling on city streets. Area treatment plants have improved in recent years, but the technology to remove many emerging contaminants — like trace amounts of pharmaceuticals and chemicals from personal care products — would be prohibitively expensive.

Three years ago, Jim Duncker, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, launched a study sampling water at different times of year from several locations along the Illinois Waterway. He found 638 different compounds. “Everything you see advertised on TV by drug manufacturers,” Duncker said — pain medications, opioids, OxyContin — “it’s all in the water.” Four were of particular interest: Atrazine, an herbicide that can disrupt pituitary and ovarian functions and “induce gonadal malformation;” Metformin, a diabetes medication that can cause intersex and reduced fecundity in fish; Venlafaxine, an antidepressant that can adversely affect predator avoidance; and Citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-, or SSRI-type antidepressant that can bioaccumulate in fish brains.

These anthropogenic bioactive chemicals occurred in abundance right up to the leading edge of the carp population, where they dissipated. Though he can’t be sure that a human-driven pharmaceutical and chemical front is holding back America’s most feared fish, Duncker said, so far the evidence suggests it’s at least a contributing factor.

As Anderson dialed Brown’s phone, she says she kept wondering, “What does this mean?” She’d known it would happen eventually, she told herself. An Asian carp would get in the Great Lakes sooner or later, but she never expected to be in the boat that caught one just short. The deckhand didn’t seem to grasp the gravity of the situation. “Everything’s going to change,” she recalls telling him. “This is affecting our future right here.”

After about an hour, officers with the state conservation police arrived. They took the cooler containing the fish, and Anderson filled out an evidence release form. The police secured the carp with an evidence tag and began driving towards Southern Illinois University.

At the university, scientists performed a necropsy on the now-famous fish. To determine its age and where it had been, they focused on the otolith, a bony structure in the inner ear, its vertebrae, and bones around the gills called post-cleithrum. It was unclear how the silver carp got above the electric barriers, but the university’s scientists learned that the 8-pound, 4-year-old male spent the last year of its life in the Des Plaines River watershed, most of which is upstream from the leading edge and some of which is upstream from the barriers. It lived for a few months, at most, in Chicago where it was caught. The university concluded its fish-dossier by saying that the response effort worked as planned and that research continued to suggest that the Asian carp population had not moved.

Nonetheless, Anderson and Brown’s catch set off several concentric reactions. According to protocol, the IDNR and many other agencies spent two weeks netting and electro-fishing more than 13 miles of the waterway. More than 20,000 fish were captured during Operation Silver Bullet, but no other bighead or silver carp were caught or even seen.

Rippling out beyond Operation Silver Bullet was the rhetorical reaction to the carp capture. Within 24 hours, it was a top story on televisions, radios, and newspapers across the U.S. and half a dozen politicians had commented or released statements. The furor reached the federal House Appropriations Committee, which gave the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers a fresh directive to report back within 45 days “regarding Asian carp proximity to the Great Lakes to determine if emergency action is needed.” Much of the outcry focused on a forthcoming plan recommending a suite of anti-carp modifications to the Brandon Road Lock and Dam, which sits a little less than 40 miles from the spot where Anderson and Brown’s fish was found. For $275 million, plus operating costs, the Corps proposed to re-engineer the downstream approach channel to the lock, add an electric barrier, water jets, noise cannons, and a lock chamber flushing system — all aimed at defending Lake Michigan from an Asian carp invasion.

But the appearance of the tentative Brandon Road plan, made public after Anderson and Brown caught their ambitious fish, only increased divisions and disagreements. One faction, which included the river shipping industry, wanted nothing to change at Brandon Road. Another side advocated shutting the lock down completely. A third, mostly made up of environmental and Great Lakes groups, demanded permanent physical barriers between lake and river.

Like Kevin Irons, Jim Duncker’s research could be used to make an argument against Brandon Road, but Duncker doesn’t trust his own chemical-front theory enough to discount the Army Corps’ plan. He thinks stopping those few rogue fish is worth it. Irons said there’s no way the June 2017 carp swam through the electric barriers, but other scientists — who didn’t want to go on the record with an opinion — are confident it did.

Typically, the Army Corps requires a local sponsor to share the cost of a federal public works project. Though Illinois’ scientists felt that it might not be necessary to do anything at Brandon Road, the state recognized that other Great Lakes states and the federal government did, indeed, want to do more. In May of 2018, the governor sent a “non-binding” letter to the Corps, agreeing to sponsor the Brandon Road plan and asking to “better understand the underlying scientific justification” behind the project while working diligently to “mitigate our ecologic, transportation, economic, and cost concerns.” For Illinois, “mitigate,” means that the federal government will offset any losses it might suffer as a result of Brandon Road. For example, if the engineered channel slows down shipping, Illinois expects the federal government to make shipping more efficient elsewhere in the state by, say, enlarging downstream locks.

The costs Illinois will bear as local sponsor have also been reduced. Normally, the sponsor pays 100 percent of the operation and maintenance costs on a federal project, but language in a bill now making its way through Congress reduces Illinois’ share to 20 percent of the potential $2 million annual cost and, under a plan proposed by Michigan, even that reduced sum will be split between the eight Great Lakes states. With Illinois stepping up as a federal sponsor, the project could be completed by 2025. Though seemingly in agreement now, Michigan and Illinois have been feuding over Asian carp since at least 2009, when the former sued the latter in an effort to shut down two locks within the Chicago Area Waterway System — a vast network encompassing 100 miles of rivers and canals connecting Lake Michigan with the Mississippi River via the Des Plaines and Illinois rivers. The case went to the Supreme Court, where Michigan’s petition was denied, but efforts to close the waterway persist.

On a bright Tuesday morning, the management of Illinois Marine Towing sat around a table at their headquarters, beside the Sanitary and Ship Canal in the industrial suburb of Lemont. Located just a few miles north of the electric barriers, IMT is one of four main companies moving bulk cargo by barge through the Chicago Area Waterway System. There was a consensus around the table that day that both the public and the government overreact to Asian carp.

Marine superintendent Mike Blaske compared them to zebra mussels, one of more than 180 non-native species already established in the Great Lakes. The mussels were initially transported in ship’s ballast water, from Western Asia and Eastern Europe to the Great Lakes. In the 1980s and 90s, they entered the Mississippi River watershed and spread through the American interior. They clogged water intakes, harmed native bivalve populations, and ate so much plankton that the Great Lakes went from murky to crystal clear in many places. Though ecologically devastating, zebra mussels didn’t attract much media attention nationally. They live below the water’s surface, Blaske pointed out, whereas silver carp jump and threaten physical harm to boaters. That’s why there’s a disproportionately “huge focus” on this particular fish, he said.

Environmentalists imagine that “these things are stacked up at the locks 10 feet deep” waiting to burst through “and just flood the lakes and destroy everything,” said Blaske. In fact, the leading edge remains three miles below Brandon Road, 14 miles below the electric barriers, and 47 miles from Lake Michigan. In a public statement last September, IMT president Delbert Wilkins said there was no scientific basis for concluding the June 22 carp passed through the barrier. He called the Brandon Road plan a “solution looking for a problem” and said more attention should be paid to the threat of Asian carp moved deliberately by humans, which he called “eco-terrorism.” Wilkins has since shifted his position, however, saying that the company is in favor of the plan “so long as new technologies are vetted and that there are no hazards to mariners.” That support comes provided that the plan “does not preclude safety while allowing uninterrupted or unimpeded commercial navigation,” — the very issues the shipping industry’s initial objections focused on.

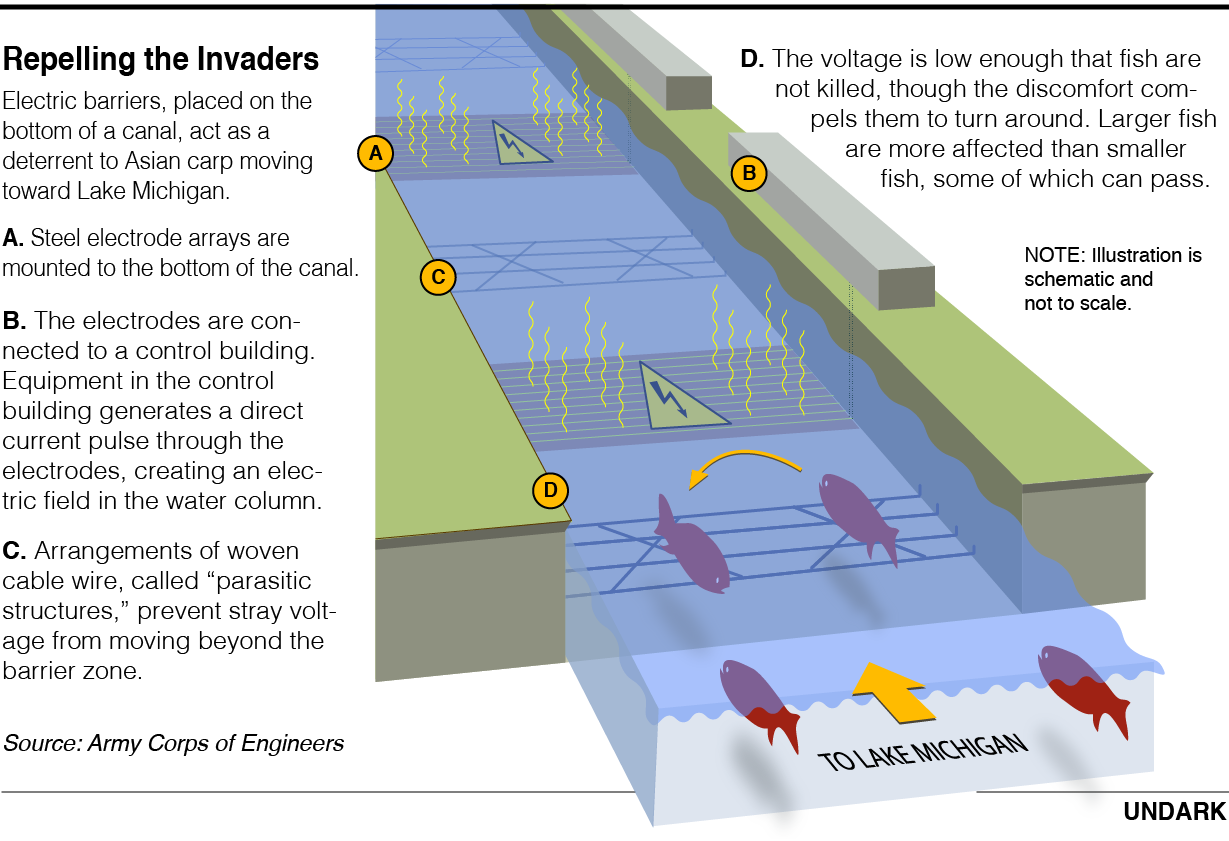

As the scope of the carp invasion became known in the late 1990s, Congress passed legislation instructing the Army Corps to prevent “aquatic nuisance species” from reaching Lake Michigan. The Corps chose to build an electric barrier system across the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal at Romeoville, Illinois. The barriers, the first of which began operating in 2002, deliver a maximum of 2.3 volts per inch at the water’s surface, pulsing 34 times per second, and collectively electrifying about 300 feet of water. According to Chuck Shea, the Corp’s barrier project manager, it would be very rare for the electricity to kill a fish. Rather, as they swim closer, they become so uncomfortable that they turn around before getting hurt.

The effect of the barriers on humans would depend on a person’s size and mass, along with other factors, said Shea, but it “could be fatal.” The rapid pulsing can interfere with the heartbeat and lead to muscular paralysis. Under U.S. Coast Guard policy, if a mariner falls in the electrified water, they cannot be touched until the barriers are turned off or they’ve moved down river.

An hour after the meeting, Blaske was on the towboat Albert C heading downstream towards the barriers. Vessels plying the electrified water must abide by a unique set of regulations. Boats and barges are ratcheted together with steel cable. If not wired properly, couplings spark. A towboat pushing a barge carrying liquid fuels or chemicals with a low flashpoint, like benzene, must wait for an assist boat to pull from the other side, grounding the flammable barge to avoid static. At the lower end of the Brandon Road Lock, a sign facing upstream instructs mariners: “Notify lock personnel if your vessel has any fish that have jumped aboard. Fish are required to be removed from vessel before proceeding upstream.”

The captain of the Albert C leaned out of the window and told his crew to get inside. No one is allowed on deck while a towboat transits the barriers, though on this summer day, there was no visible effect as the craft glided though the electric water. Other than warning signs and a yellow fence, several squat, bunker-like concrete buildings were the only evidence of the barriers. The amount of money the government has spent to stop Asian carp, “Will make you gag,” said Blaske. “I just think it’s crazy.”

When finished in 2021, the electric barriers at Romeoville will have cost tax-payers $268 million, plus $15 to $20 million per year to operate and maintain going forward. (This does not include the $275 million price tag for the Brandon Road project.) Though it is automatic and runs constantly, the Romeoville barrier system has a staff of eight during business hours (and on call at other times) and one on nights and weekends. It is not known how many, if any, Asian carp have encountered the barriers. In all the monitoring since its construction, there has never been a documented sighting.

The Albert C passed a fish surveyer with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. “He’s been pulling up a lot of net and I haven’t seen one fish go through,” said Blaske.

The specter of a complete shutdown of the waterway, though defeated in 2010 when the Supreme Court refused to hear Michigan’s request to close the two locks closest to Lake Michigan, gained strength after the June 22 carp-catch. River shippers like IMT say the consequences would be catastrophic: Millions of tons of fuel, steel, grain, sand, and concrete transit the waterway each year, and a closure means that those commodities would have to travel by road or rail, vastly increasing costs and adding exponentially more traffic to highways and train tracks that already rank among the nation’s most crowded.

On a typical early summer day, IMT can have 140 barges in Lemont, waiting to move up or down river. According to one estimate, one barge carries 70 semitruck-loads. How else could they move almost 10,000 trucks’ worth of goods through metropolitan Chicago? “I have 170 vessel employees,” Blaske said, and close to 1,000 people work on vessels across the area’s four towing companies. Closing the waterway would, he said, bring “devastation to the working class in the Chicago area.”

Meleah Geertsma disagrees. A lawyer for the Natural Resources Defense Council, which supports closing the waterway and views the Brandon Road plan as only an interim step, Geertsma said that shipping on the waterways around Chicago is “essentially a dwindling mode of transportation that at the same time is pretty critical to a few types of goods.” But Geertsma added, “the use of waterways in general is on a multiple-decade decline.” The barge industry, she argued, exaggerates their importance and the impacts of potential disruptions. “You have an industry that can’t carry its own costs trying to block a process for controlling carp that has much bigger implications,” Geertsma said. “Since they’re so dependent on the federal government, shouldn’t they be the ones asking for consideration and not the ones driving the agenda?”

At the same time, Geertsma admitted that fears of Asian carp invading the Great Lakes are often exaggerated. It would be “horrible” if carp became established in the lakes, because they would out compete some native fish, Geertsma said, but there’s “still a big question” as to whether they would thrive or even survive in Lake Michigan’s relatively cold, nutrient-poor water.

This doesn’t change the fact that, according to the NRDC’s analysis, very little is shipped by water between Chicago, or points south, and Lake Michigan. Some materials move to and from the city by barge, but most of the tonnage that is recorded transiting Brandon Road, for example, is destined for industrial areas south of Chicago. Walling off the waterway further north, Geertsma argued, would not block a “robust throughway of commerce.” She thinks the economic impact would be much less than barge advocates claim.

These and more strident sentiments were on full display at a public meeting in September, convened by the Corps to get feedback on the Brandon Road plan, in Muskegon, Michigan — 120 miles as the fish hawk flies across the lake from Chicago. Many of the Michiganders feared that Asian carp would destroy broad swaths of their livelihood. As each person stood up to speak, the value of what was at stake seemed to rise: from $7 billion for the Great Lakes fishery, to $26 billion for Michigan’s outdoor recreation economy, to $62 billion for wages derived from Lake Michigan in that state. Substantial applause went to advocates of “total separation” and “lock closure.” Several comments verged on hysteria. One person connected the Asian carp threat to immigrant farm workers, lack of sanitation, and even E. coli.

Conspiracy theories notwithstanding, a serious effort exists to reestablish the Lake Michigan and Mississippi watersheds. The Great Lakes Fishery Commission, Michigan Environmental Council, the states of Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Michigan, the NRDC, Michigan Democratic Sen. Debbie Stabenow, and a host of alliances and coalitions all favor separation in some form. Another group, the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, published this faction’s manifesto, called “Restoring the Natural Divide,” in 2012.

Shipping, sanitation, and flood control are the three most enduring functions of the area’s highly engineered system of rivers and canals, and the most expensive and difficult aspects of undoing it. If physical barriers are placed within the Chicago Area Waterway System, a portion of Chicago’s sewage system would have to be re-plumbed and the city’s wastewater treatment plants would have to be retooled to process water to much higher standards for discharge into the Great Lakes. The physical barriers would also disrupt shipping. The Initiative’s paper proposed trans-loading facilities on the barriers, where cranes or other equipment would unload barges on one side and re-load them on the other. But by any estimate, restoring the divide would cost billions of dollars.

“The conversation about complete separation is divisive right now,” said David St. Pierre, executive director of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago, which oversees sewage infrastructure and treatment plants, as well as maintains water levels in the Sanitary and Ship Canal. Most separation scenarios, none of which St. Pierre views as realistic or viable, would require a substantial reengineering of the District’s infrastructure, with implications for flooding and water quality in the waterways and the lake. When it comes to finding solutions, he sees the environmentalists and the barge industry retreating to their ideological corners, with an unwillingness to compromise so entrenched that he compared it to religion.

“You can’t elevate transportation or invasives,” he said, “above everything else.”

Kevin Irons and his colleague, Matt O’Hara — also with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources — glided across a muddy, opaque stretch of Illinois River near Starved Rock State Park and stopped beside Tracy Seidemann’s boat, where a 1200-yard net was being handed aboard. A silver carp was tangled in the net about every five feet, and when the deckhand got to one, he hooked it through the eye. Holding the muscular, hydrodynamic fish aloft, he carefully peeled the monofilament down around the body and tail. The pinkish net, strung with small floats and heavier black line, piled up in the boat’s forward compartment. The carp piled up in the middle, where they grew darker in the sun. Seidemann, a commercial fisherman, stood in the stern, backing slowly on his 200-horsepower Suzuki. A biologist with the IDNR tallied the catch on a blood-spattered clip board. On average, the ratio of Asian carp to every other kind of fish that day was five to one, though the gear and location were both optimized to target carp.

Irons and O’Hara have been monitoring carp in the Illinois River since the 1990s, when a day of gill netting would come up with one or two. Beginning around the year 2000, their nets started coming up with hundreds. In 2010, they began “harvesting” on a large scale using commercial fishermen. While a lot of people do a lot of talking on the issue, Irons’ and O’Hara’s team is widely considered to be the only one doing anything about it. They remove upwards of 1 million pounds of carp from the Upper Illinois River each year, while commercial fishermen downstream can bring in 3.5 to 8 million more. Yet still, in some places, 75 percent of the river’s biomass — meaning the aggregate of all organic material — is Asian carp.

Irons draws hope from the story of cod, which were hunted across the vast Atlantic Ocean to the brink of extinction. “I think it’s really possible to use fishing as a strategy to, probably not eradicate, but get us to a more comfortable place,” reducing the risk to the Great Lakes and freeing up plankton for other fish, he said. Irons’ program is showing results: between 2012 and 2014, scientists documented a 68 percent decrease in Asian carp populations in the upper reaches of the Illinois River. In 2017, Irons said, this number was approaching 93 percent in the stretch of river below the leading edge.

But to keep the population from climbing back up, the harvesting program needs to continue —forever — at a cost of $1.2 to $1.6 million dollars per year, though Irons says the costs could shrink if fishing intensifies downstream. So far, the bill has been footed by U.S. taxpayers in the form of grants from U.S. EPA and the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, but federal funds are annually subject to politics. President Trump’s 2019 budget proposes a 34 percent cut to the EPA. If Irons’ program and others combating Asian carp were to lose their funding, the population would quickly rebound. Before long, bigheads and silvers would overwhelm the leading edge and truly challenge the electric barriers.

Seidemann, a big man in his mid-40s, smoked cigarettes and had a snapping turtle tattooed on his sunburned arm. He had been working with Irons for 8 years. At best, he said, he could make $1,000 per day fishing his home waters near Savanna, Illinois, catching common carp, buffalo, and catfish for the retail trade. He makes more money — $85,000 to $100,000 per year — working five days a week, 24 weeks a year for the IDNR, netting fish that would have wasted his time before. As the sun reached its early-June apex, the carp in Seidemann’s boat went from ankle-, to knee-, to thigh-deep.

Worldwide, no fish is farmed in greater numbers than Asian carp, but the U.S. market for it is comparatively small. An Illinois company called Schafer Fisheries says it sells 10 to 15 million pounds annually, 30 to 40 percent of this domestically. Mike Schafer, the company’s owner, said that the IDNR fishing program has actually hurt his business. “IDNR has employed a lot of our fisherman away from us,” he said, “so we don’t have continuity of supply.” For him, the millions of dollars spent on Asian carp controls is “a fiasco” — government paying government at the expense of the private sector.

While Irons’ boat was alongside Seidemann’s, he recalled the tasty carp hotdogs that Schafer briefly made. Then he told Seidemann and the other commercial anglers about a place in Kentucky paying for fresh Asian carp, brought down on ice. They didn’t seem enticed. The IDNR doesn’t maintain food quality fish, so every couple of days, Irons’ team fills a 53-foot truck with about 40,000 pounds of carp. A load last summer went to a fertilizer company in South Dakota called Holy Carp, but some truck loads end up in landfills.

Still, Irons is hopeful that Illinois can turn that surplus into something profitable, and in turn find a free-market solution to the Asian carp threat. Such a solution would already exist, Schafer claims, if government resources had been focused on this idea a decade ago. According to him, catching, selling, and eating, is far simpler and far cheaper than electrified barriers or disruptive concrete walls.

In the last days of 2017, Irons and O’Hara were at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, which operates the largest nonmilitary dining center in the U.S. and has an even bigger one planned. Chef SooHwa Yu entered the room bearing a platter. On a bed of wilted greens, garnished with green onions, parsley, and cilantro, and tossed with soy sauce and sesame oil, lay a bighead carp fried Cantonese-style. A thin white line of jaw bone protruded from the brown fry batter.

“This is how we’re going to solve the problem,” said Irons excitedly, “This is the end game.”

Wayon Smith, III, a fast-talking food service administrator for the school, appeared behind the biologists. The university pays $3.60 per pound for frozen tilapia fillets, Smith said — one of their cheaper proteins. “Carp is $2.65-2.70 for fillets and whole fish are even cheaper,” he said. Smith remembered when he first tasted Asian carp. “I felt like I was lied to,” he said, “all the time, I was told it tasted bad — this is a great tasting fish.”

But Asian carp fillets are layered with thin L and Y shaped bones, so labor intensive to remove that boneless fillets cost $10 per pound. At that price, Smith said, “You might as well go for swordfish or salmon.” In 2016, the university experimented with using ground Asian carp in chowders and tacos. In March 2017, they served it bone-in for the first time. They were amazed: Students didn’t seem to care about what, until then, was considered an insurmountable barrier.

“I thought we would get a lot of negative comments about the bone-in,” he said. “We’ve had only one all semester.”

Irons explained that Illinois spent $1 million dollars on a marketing study aimed at developing a commercial Asian carp fishery. Longer term, the state is looking for $32 to $40 million from the federal government. Spent over seven or eight years, Illinois says this will be enough to make that industry self-sustaining. Currently, most processors pay $0.10 or $0.15 per pound for bigheads and silvers, Irons said, so fishermen throw them back. Illinois is hoping to find a way to raise the price to $0.20 to $0.30 per pound (which Schafer says he currently pays for grass and bighead carp.) At those rates, Irons hopes it will be more profitable to catch Asian carp by the ton.

Until then, the mere existence of a bighead or silver carp population lurking somewhere in the riverine landscapes around the Great Lakes — and most certainly the mysterious appearance of any Asian carp that manages to breach the garrisons designed to keep it at bay — will stoke bitter debates over what more, if anything, can or should be done about it.

After all, Irons said, “carp is a four-letter word.”

Tyler J. Kelley is a freelance journalist based in New York. He is currently working on a book about inland waterway infrastructure.

UPDATE: An earlier version of this piece misidentified the nonprofit where Meleah Geertsma works. It is the Natural Resources Defense Council, not the National Resources Defense Council. The piece also incorrectly stated that a barge transporting caustic soda would require an assist boat to transit the electric barrier system at Romeoville. Given caustic soda’s high flashpoint, a barge carrying the compound would not require an assist, though one carrying benzene would. The story has been updated.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Hello, after reading this awesome piece of writing i am

too happy to share my knowledge here with mates.

Sounds like american carp, too many bones. Only good for the garden.

Probably a few thousand bighead and silver carps escaped in AR around 1980. 35 years later I estimate there are 30 to 60 million fish in 6,400 river miles of the Mississippi Basin. Every year these fish expand their territory. There is a new land barrier at Eagle Marsh near Ft. Wayne, IN and plans in place for barriers in Ohio. A lock in Minneapolis was closed and there is a study to close a lock in the Erie canal. The focus in on IL but the problem is much greater. From 2011 to 2018 the Federal government spent $420 million mainly for barriers, followed by education/enforcement/early detection and finally population control. Harvesting is the only population control in place. As noted above it is expensive. The $1.1 to $1.6 million per year for the last 5 or 6 years was for just 50 miles of river. The $12 million government pesticide solution is based on Antimycin A/beeswax. Antimycin A is a red labeled, highly hazardous, broad spectrum pesticide that the EPA wanted to remove as a legal pesticide in 2005. There is no commercial source of Antimycin A. Beeswax must be used because if the fish even get a hint of Antimycin A, they will not eat the formulation. I invented a selective (digestive like the USGS Antimycin A/beeswax), safe (all FDA ingredients) and low cost (1/12 to 1/3oth of the USGS Antimycin A raw material if the government could buy them). For more information see http://www.carpfree.com or email me at [email protected]. No pesticide, the bighead and silver carp will get into the Great Lakes, it is just statistics.

Some clarifications that might make the government and environmental efforts make more financial sense:

1. The first electric barriers aren’t just to keep Asian carp(s) out of the Great Lakes, but other species going in the other direction as well; they were originally built to keep Eurasian round goby—a highly invasive fish in the Great Lakes—from entering the Mississippi Basin. The fish beat them out, however, being found downstream of the barrier before it was finished.

2. There are currently some 13 non-native fish species poised to make their way from the Mississippi Basin into the Great Lakes or vice-versa through the Chicago-area canal system, which considerably raises the stakes for its utility and makes the price of inaction far greater than current costs of prevention.

3. Maintaining the current Great Lakes $7 billion/annual fisheries jointly costs the U.S. and Canada upwards of $30 million a year in sea lamprey control, and they have been doing this for 63 years; if they had to control Asian carps as well the cost would be unaffordable and the fisheries would collapse—never mind the environmental and ecosystem damage that would likely do the same.

4. Climate models and risk evaluations for Asian carps (most done by Canada’s DFO but including info from U.S. agencies) show that they would do just fine in most of the Great Lakes (Superior excepted). Yet, allowing the four species conflated under the rubric of “Asian carp” into the Great Lakes would be like dropping a trophic bomb in the lakes—a phytoplanktivore (silver carp), a zooplanktivore (bighead carp), a molluscivore (black carp), and an herbivore (grass carp) could combine to do a huge amount of damage to the already tenuous base of the Great Lakes food chain. In addition, for instance, grass carp (which have now been found in small numbers in Ontario, Erie and Michigan) vector some serious fish parasites and eat up to 40% of their body weight in aquatic plants a day—plants that are used by other fish to lay their eggs on. All in all it will be a disaster if any of these species really get going in the lakes.

What about often overlooked but very serious health advisories for fish in the waterways where carp are found? Most states have advisories for mercury, PCBs and other contaminants that advise a limit on the safe consumption of local fish, which is even lower for pregnant women and children and could have dangerous health effects if consumed regularly.

Is their any research being done by biologists to make them sterile and limit their reproduction? With all the money spent could this be an alternative?

.

They will simply breed in the rivers and multiply, eventually overwhelming the great lakes.

I have a chum that will draw them into areas to be harvested. Instead of chasing them why not call them to you.

Pitchin1 – A 2017 study by the USGS predicted they would have sufficient food and habitat in Lake Michigan within at least a mile of shoreline, in bays, inlets, and river mouths. https://www.usgs.gov/news/asian-carp-would-have-adequate-food-survive-lake-michigan

The environmental and conservation coalition is not pushing for a permanent separation, as this article continuously claims. In public comments, groups including the National Wildlife Federation have advocated for the Brandon Road plan as an alternative to completely shutting down navigation. The claim that the front line of Asian carp hasn’t advanced in decades is a little misleading, too: decades ago, there were only a few fish where now there is a population. And if you make a market for Asian carp, then you’ll induce illegal introductions by people looking to cash in on that market.

There is not enough current in Lake Michigan for Asian Carp to spawn, the water temps in upper lake Michigan are below needed spawning temps. The summer water temps in lower lake Michigan are on the b0ttom edge of needed spawning temps. The fish would simply die of old age in the lake if they did make it past the chemical barrier.

Could you please identify the tributaries connected Lake Michigan that provide the current and temperature needed for Asian Carp to spawn and list them. if there are none we are spending a lot of money to keep a few fish out of the lake that would simply die of old age.