When physician Gabor Maté published “In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction” in 2009, most doctors, he wrote, still viewed addiction as a disease determined primarily through genetics, or as something that stems from lack of willpower. Maté argued that addiction’s true roots reside not in disposition or only in genes, but primarily in trauma. The book became an award-winning best-seller that, along with a growing body of scientific evidence, started to change how we understand and treat addiction.

Now, Maté is once again attempting to shift the conversation, this time about health at large, through a new book, “The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture,” which he co-wrote with his son, Daniel Maté. Across nearly 500 pages, Maté (who assumes the narrator’s voice) draws from extensive research of scientific literature and decades of firsthand experience to build a bold, wide-ranging case about the origins of much of what ails us. He posits that everything from trauma and depression to hypertension and even some forms of cancer are symptoms of living in a society that runs counter to our biological needs and fails to recognize how connected our well-being is to everything and everyone around us.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture,” by Gabor Maté, with Daniel Maté (Avery; 576 pages).

As he writes, “I have come to believe that behind the entire epidemic of chronic afflictions, mental and physical, that beset our current moment, something is amiss in our culture itself, generating both the rash of ailments we are suffering and, crucially, the ideological blind spots that keep us from seeing our predicament clearly, the better to do something about it.”

“The Myth of Normal” seemingly arrives at just the right moment. The Covid-19 pandemic, inequality, climate change, and political divisiveness have contributed to a creeping sense, for many people, that something is fundamentally awry. Mental health diagnoses are escalating across the developed world in all age categories, Maté points out, with 21 percent of U.S. adults — or nearly 53 million Americans — experiencing mental illness in 2020. And all of this is in spite of “spectacular economic, technological, and medical resources,” he writes.

Yet the reasons behind this suffering remain elusive, as do the solutions. For Maté, though, it’s not that we’re getting sicker, it’s that “our social and economic culture generates chronic stressors that undermine well-being in the most serious of ways.”

Maté dedicates the first three-quarters of his book to chronicling our current health challenges and providing the scientific backing to explain them. He starts with trauma, which he sees as one of the most prevalent stressors driving our health crisis and defines as a type of “psychic injury, lodged in our nervous system, mind, and body.”

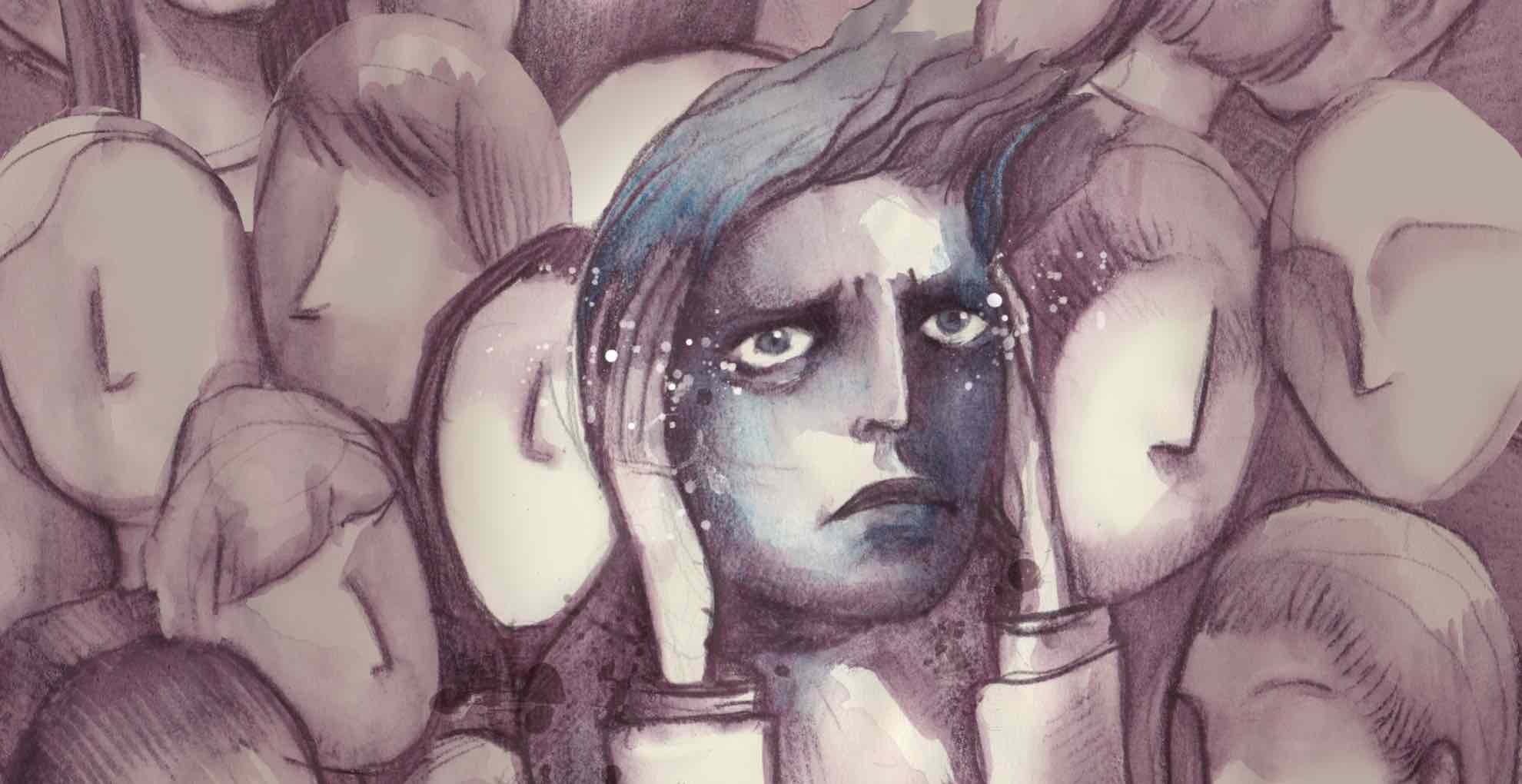

Whether in a neglected child or a soldier at war, he argues, trauma originally develops as a defensive mechanism to protect and relieve the sufferer from pain by disconnecting them from themselves, others, and the world at large. While trauma can help us survive an abuser or the horrors of war in the moment, its effects on our brains, bodies, and behavior can linger long after the threat has passed. When this happens, “our miraculous talent for adaptation” is turned into a liability, Maté writes, and we become tethered to the past, unable to live fully in the present.

Trauma can form in response to bad things happening — a war, a rape, a natural disaster — but it can also develop in the absence of good things that should happen but did not, for example, in a child whose emotional needs were not met, or who was not seen and appreciated for who they truly are, Maté writes. Evidence also increasingly indicates that trauma is multigenerational, passed from parents to their children through behavioral, prenatal and epigenetic mechanisms. Contrary to the popular idiom that time heals all wounds, trauma also tends to hang over us like a shadow, unresolved, unless we face it head-on through therapy or some other form of healing. “By banishing feelings from awareness, we merely send them underground, a locked cellar of emotions that will continue to haunt many lives,” Maté writes.

Mainstream psychiatry still views most mental health problems as mainly stemming from imbalances of brain chemicals, which in turn are primarily determined by genetics. Maté argues that trauma, in fact, underlies “much of what gets labeled as mental illness.” This includes not just post-traumatic stress disorder, but also conditions as variable as addiction, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anorexia, and schizophrenia.

Trauma and the associated stresses it causes in the body are also linked to a dizzying array of physical problems. Research has revealed, for example, an increased risk of ovarian cancer in women diagnosed with PTSD; a higher incidence of heart attacks in men who were sexually abused as children; heightened inflammation and illness — and shortened life spans — in Black people who regularly experience racism and discrimination; and a greater likelihood of mental health disorders, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and other deleterious conditions in people whose mothers experienced high levels of stress while pregnant.

Trauma and other chronic mental and physical illnesses are propped up by many societal and cultural factors, Maté continues. These illnesses are, to a large extent, “a function or feature of the way things are and not a glitch; a consequence of how we live, not a mysterious aberration.”

We humans are evolutionarily programmed with a number of core social needs that are mandatory for our well-being, he explains, including connecting with others, experiencing a sense of belonging, and believing that we serve a greater purpose than just ourselves. But our current system of dog-eat-dog capitalism runs counter to these needs, the authors maintain, including by defining a person’s worth by their ability to consume — an inherently self-serving endeavor.

In Maté’s view, we’ve also created a society that actively reinforces disconnection from ourselves, others, and nature. “Work pressures, multitasking, social media, news updates, multiplicities of entertainment sources” — all “induce us to become lost in thoughts, frantic activities, gadgets, meaningless conversations,” Maté writes, obliterating the present and distracting us from the act of living.

Our ability to thrive is further eroded, he continues, by numerous other factors: We live in insulated nuclear family units far from our extended families and disconnected from a broader community; we crowd into cities surrounded by concrete rather than trees, and where we do not know our neighbors; we’ve seen all forms of social participation, from church-going to volunteerism, decline; and we’ve supplanted person-to-person interactions as simple as buying a book or having a conversation with a friend with virtual platforms. “Social creatures by natural design, we have become fish out of water,” Maté writes.

Maté dedicates the last quarter of his book exploring “pathways to wholeness,” or means of getting out of the unhealthy, unhappy predicament we’ve created for ourselves. He explores a number of possibilities for self-betterment, from psychedelic-assisted therapy to a daily or weekly self-inquiry exercise he designed that consists of asking yourself number of questions, such as “In my life’s important areas, what am I not saying no to?” and “Where have I ignored or denied the ‘yes’ that wanted to be said?”

Maté readily admits that he does not know what it will take to return us to a healthy normal. Almost certainly, though, “the real changes need to happen at the societal level,” he writes — and there is some hope that this will happen. As he points out, the fact that we can work toward wholeness and betterment at an individual level indicates that this process can occur on a societal level, too. “When we can look soberly at what we as a culture have normalized about health and illness, and realize that it is not, in fact, the way things are meant or fated to be, there arises the possibility of returning to what nature has always intended for us,” he writes.

Maté’s diagnosis about the true origins of what ails us is not yet widely accepted by the medical establishment, and neither are some of the solutions he outlined for healing. But he does make a persuasive case that could help nudge that process along, and — if he’s right — ultimately move humanity toward a healthier, happier, and more connected world.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I found it astounding that you don’t mention the way in which Dr. Mate links the patriarchy (yes, he uses that term) to the health problems of women and children over such a long time. His holistic approach to trauma and how it affects us is a gift for women’s equality, among other things. Yet your review hardly mentions women at all….

Thank you for taking the time to read the review. There’s a lot that has to be left out in a 1300-word summary of a nearly 500-page book. “Inequality” is the word I used to capture the issue of sexism, racism, ableism, etc. I’m glad you enjoyed the book and found Maté’s approach to be useful.