Bringing Andrology — and Male Infertility — Out of the Shadows

Adam Glogau knew he had reached rock bottom when, in March 2014, he found himself in his living room with a 9mm handgun in his mouth. He felt helpless and angry, with nowhere to turn. He and his wife had tried for years to have a child, but his semen contained almost no sperm, which left little room for hope.

Glogau cuts a dynamic figure with glowing blue eyes and rimless glasses. Now 39, he is an eloquent speaker and a youth pastor at the Grace Downtown church in Winchester, Virginia, which is known for providing support to victims of the opioid epidemic. Six years ago, however, Glogau’s life was coming apart. He and his wife had fostered two children, but the arrangement ended badly, with the children going to another family. Then Glogau lost the job he’d held for seven years. “I felt like I was a failed father, I was a failed husband, and now I’m a failed man because I can’t keep a job,” he says. “It was whammy after whammy after whammy.”

From an early age, Glogau says, men are taught to be “the hunter-gatherer, the provider, the head of the household, and we are supposed to, in biblical terms, go forth and multiply.” That moment with the gun was his lowest point. In the absence of a biological child, Glogau felt he had let his wife down. He was overwhelmed by a profound sense of shame and unworthiness.

Although men are just as likely as women to have fertility problems, ads for fertility treatment typically feature women holding giggling babies in the air or intimately touching a child’s face. Yet research suggests that reproductive issues have a profound emotional impact on men, too. Across the globe, masculinity is marked, in part, by the ability to have children — a demonstration “that you’re a fertile, virile man,” says Esmée Hanna, a sociologist at De Montfort University in the United Kingdom. In her research on men experiencing infertility, Hanna has documented feelings of loss, anger, frustration, and guilt.

According to some experts and health care providers, this woman-centric approach to fertility has implications for men and women. Women are being overtreated and subjected to invasive procedures, while men aren’t getting the medical and mental health care that they need. And all of this is unfolding at a time when sperm counts are dropping.

Shadowed by taboo and embarrassment, the emotional experience of male infertility has been tucked away and ignored by the medical industry and often by men themselves. Compared with women, men are less likely to want to talk about their struggles, says Kelly Da Silva, a support coordinator at Care Fertility in the U.K. But men are now starting to speak out, and innovative practitioners are figuring out how to meet their needs. “You have to do it their way,” says California-based urologist Paul Turek. “You have to do it anonymously, quietly, and it has to be valuable for them.”

Men don’t necessarily need someone to pat them on the back or give them a hug, says Turek. “Although,” he adds, “a lot of them respond really well to that.”

The treatment of the male reproductive system is a somewhat obscure field known as “andrology,” which brings together disciplines such as urology, anatomy, and biochemistry. Though andrology’s roots in modern medicine can be traced back decades, the field is widely viewed as a neglected step sibling to obstetrics and gynecology. As recently as 2017, only three countries — Germany, Hungary, and Egypt — recognized it as a medical subspecialty.

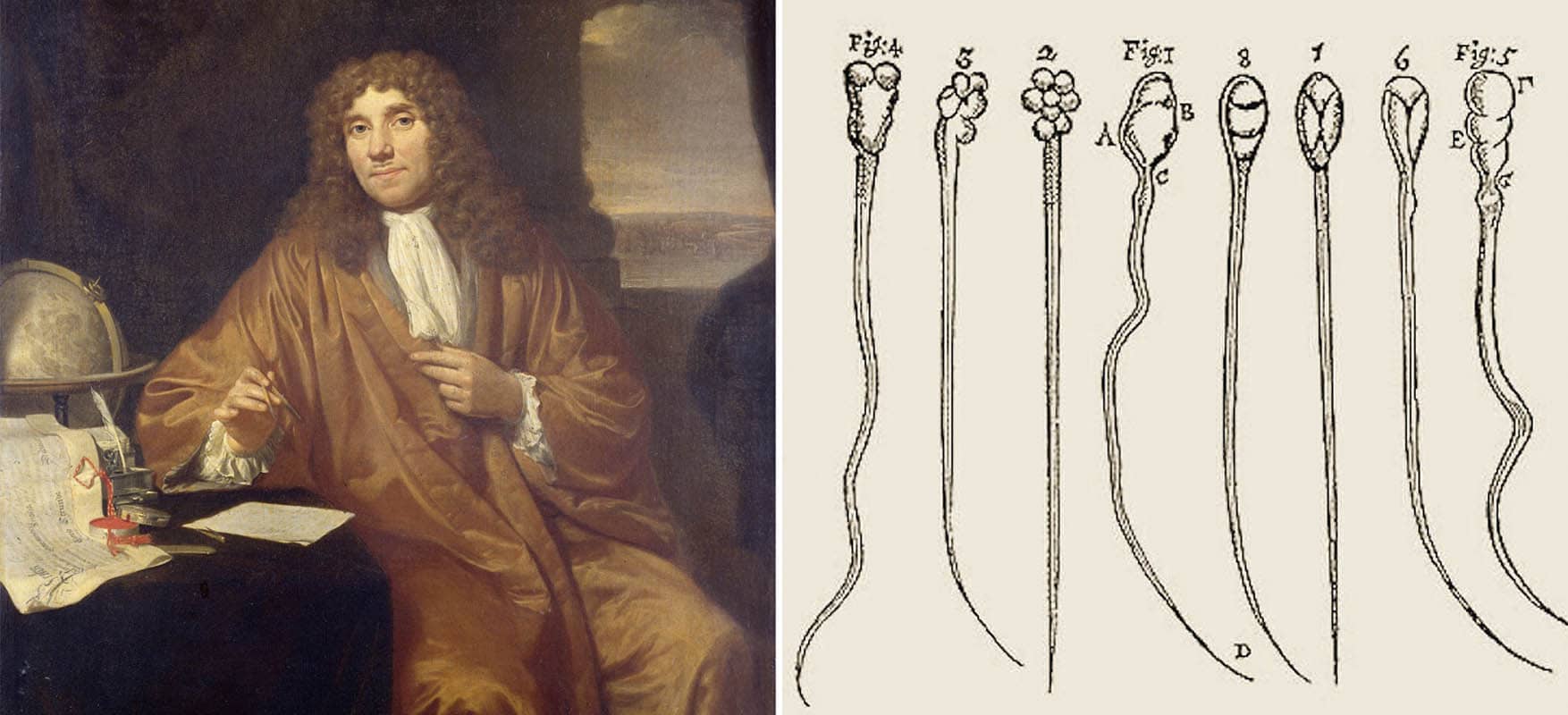

Of course, the medical community’s research into sperm stretches back much further. In 1677, shortly after the invention of the microscope, Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek sent a report to the Royal Society of London: A medical student in Leiden had discovered that semen contains sperm, a finding van Leeuwenhoek subsequently confirmed by analysing his own ejaculate. Van Leeuwenhoek was amazed to see “so great a number” of tiny sperm, each one “furnished with a thin tail, about five or six times as long as the body, and very transparent.” He noted that “they moved forwards owing to the motion of their tails like that of a snake or an eel swimming in water.” Writing in Latin, van Leeuwenhoek made clear that the sample came “without sinfully defiling myself” but “as a residue after conjugal coitus.”

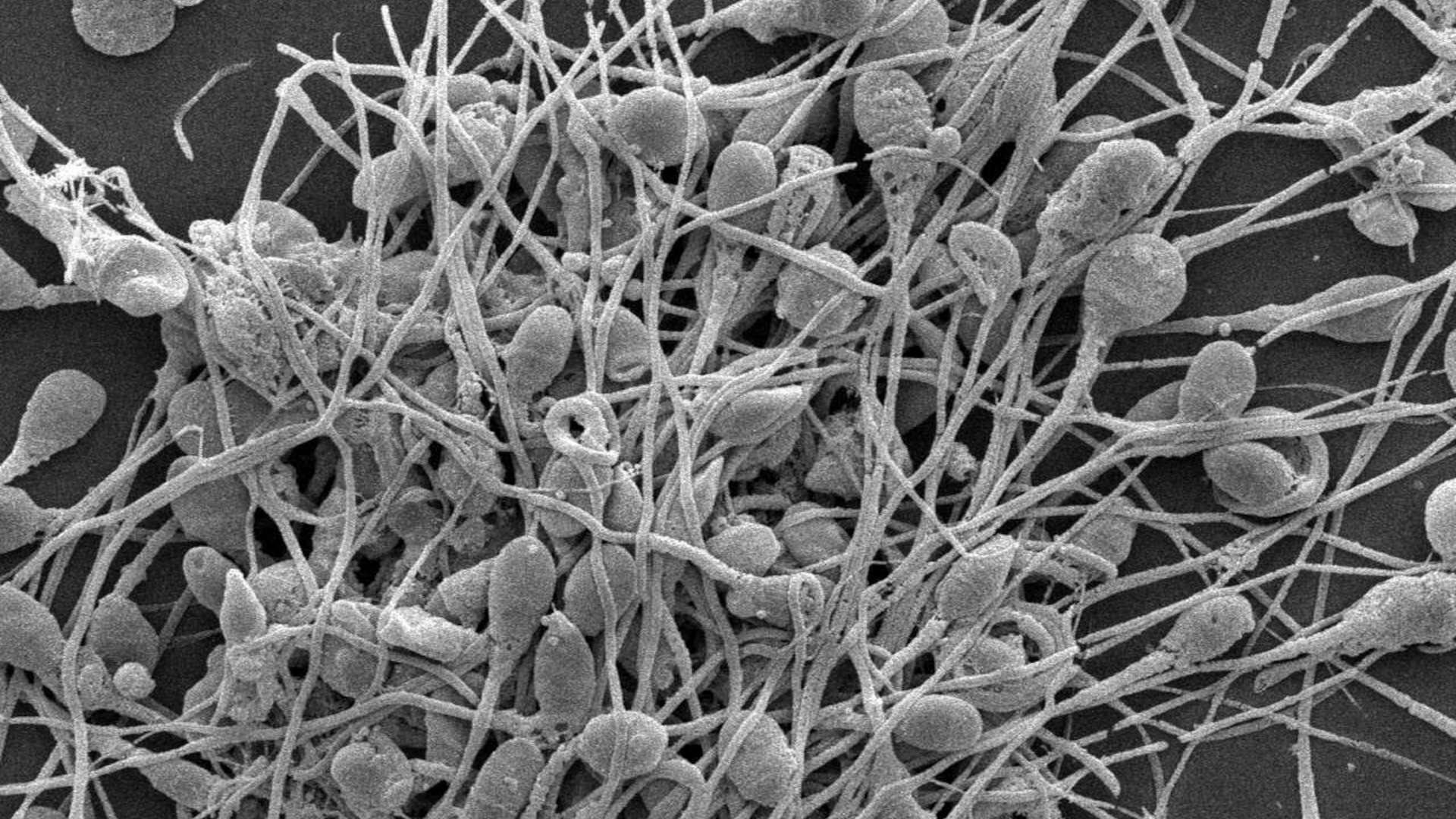

Van Leeuwenhoek’s description turned out to be impressively accurate. Recent discoveries have simply filled in the details, revealing an immensely complex picture. The sperm is made up of three parts: The head carries the DNA, the father’s genetic contribution; the middle section produces energy that allows the sperm to move; the tail wriggles and whips back and forth propelling the sperm forward. Semen — the fluid surrounding the sperm — helps the sperm along, supplying nutrients and forming a buffer for when the sperm enter the vagina.

It takes three months for sperm to mature, as they travel through a series of different locations in the man’s genitals. After being produced in the testes, they move to the epididymis (a single conduit to the vas deferens, which, if unfurled, would be about 20 feet long), where they become mobile and acquire the ability to detect the fluid women release when ovulating. After sperm are ejaculated through the urethra during sex they proceed up the female genital tract, interacting with uterine fluids. The first sperm cell to arrive at the egg releases enzymes that allow it to penetrate inside the egg cell.

Problems can occur throughout this process, and men’s reproductive issues are acknowledged to play a role in 50 percent of cases of infertility. The tail alone contains more than a thousand different proteins, which, if they malfunction, can hinder the sperm’s movement. If a man’s semen has too many white blood cells it reduces fertility, although doctors haven’t yet figured out why. Low sperm motility, low to no sperm count, and abnormal sperm shape — with misshapen heads, for example, or double tails — may all hamper a man’s ability to reproduce.

In the second half of the 20th century, the fertility industry bloomed, with the arrival of the birth control pill and development of in vitro fertilization (IVF), which allowed doctors to collect eggs from women and fertilize them in a lab for later implantation into the uterus. But treatments for male infertility never took off, partly as a result of these innovations focused on the female body, which in some cases allowed couples to leapfrog over the man’s fertility problems. Today, when couples first visit fertility clinics, the specialists they encounter are often gynecologists.

That’s proving to be a problem now, in particular, as we face what some scientists have called “a global crisis in male reproductive health.” Sperm counts have dropped by more than half in Western countries over the past few decades, while abnormalities in men’s reproductive systems are on the rise, and the quality of sperm has also deteriorated, battered by pollution, plastics, and poor diets. Chemicals present in everyday objects like canned food, water bottles, and kids’ toys have been linked to degraded semen quality, while air pollution is also known to harm sperm (and has been shown to impact women’s reproductive health). A man’s age and weight have also been linked to poor quality sperm.

Writing in the Journal of Andrology last year, Christopher De Jonge, director of the University of Minnesota Medical Center’s Andrology Program, and Christopher Barratt, head of the Reproductive Medicine Group at the University of Dundee in Scotland, argued passionately for action to protect men’s reproductive and general well-being. “Sperm counts may be a barometer for overall male health,” they wrote, warning that the decades-long decline should serve as a wake-up call for the medical community.

And yet, when couples struggle to conceive, women generally bear the brunt of treatment. This is because advanced IVF techniques offer a relatively effective fix to fertility problems, but the approach places a burden on the female body that two scholars in Canada, Vardit Ravitsky, an associate professor of bioethics at the University of Montreal and Sarah Kimmins, an associate professor of reproductive biology at McGill University, characterize as “unjust,” even “scandalous.” In IVF, fragile sperm are deposited directly at the egg in a lab dish, allowing them to avoid the arduous journey up the fallopian tube. Some forms of IVF go a step farther: In intracytoplasmic sperm injection, or ICSI, a lab technician selects a single sperm and injects it directly into the egg, allowing it to bypass the challenge of pushing through the egg’s sometimes tough exterior.

All of this exposes women to painful, sometimes harmful, medical interventions that include side effects such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and stroke. Scientists have additionally found that fertility treatments may increase the risks of breast cancer in women over 40 because they tinker with the body’s natural levels of estrogen, and there are suggestions that the procedures may slightly increase women’s vulnerability to ovarian cancer. According to Jonathan Ramsay, a urologist at Hammersmith Hospital and Imperial College London, IVF’s focus on women’s bodies means that fertility treatment is “the only time when one gender has treatment for the other gender’s problem.”

But current treatment practices pose a problem for men, too, because they allow physicians to ignore whatever is rendering the man infertile. For both sexes, reproductive problems can serve as a canary in the coalmine, foreshadowing illnesses such as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. “Numerous scientific publications report that chronic illness, disease, and premature death in men are linked to their reproductive health,” De Jonge and Barratt note.

Progress towards infertility treatment options for men has inched along at a glacial pace. Channa Jayasena, an endocrinologist who specializes in andrology and is also based at Hammersmith Hospital and Imperial College London, says that although infertility affects many men, it is a reality society has essentially ignored. “We’ve never developed any treatment to improve a man’s sperm count,” he says. “The treatment is simply treating his partner with something that most people in the world cannot afford and is potentially dangerous.”

Even basic testing is coming up short. The World Health Organization set out standard parameters for healthy semen in 2010, but some scientists say that new information about the molecular, cellular, and genetic makeup of sperm must be taken into account and the global reference points should be updated.

Tests for genetic abnormalities, hormone analyses, and ultrasound scans may also be needed to provide a more complete picture. Such testing can check for obstructions like varicose veins in the testicle, called varicocele, which can impede sperm production by blocking the testicle, even causing it to shrink. But it is rarely offered to male patients. No surprise, then, that men on the popular web forum Reddit write post after post, asking others to interpret their semen test results like tea leaves, sharing intimate details about color, volume, viscosity, appearance, pH, morphology, motility, and sperm count. “Care to comment on my semen analysis?” wondered a 34-year-old recently, posting his results. The question is posted so often that it is addressed in the FAQ.

Even if more sophisticated tests were commonly performed, solutions are in short supply, experts say. There are clear indications, for example, that damage to the sperm’s DNA called DNA fragmentation underlies recurrent miscarriages and other fertility problems. But the American Society for Reproductive Medicine does not advise routine testing because medical treatments do not yet exist.

When Glogau first met his wife, Mysti, he imparted three details about himself that he felt were crucial as they chatted over ice cream. He was a Republican; he was not a virgin; and if she stayed with him, she might never be able to have kids. He was born with an undescended right testicle, which, after an unsuccessful surgery while he was still a baby, “just dissolved over time.” The left testicle was in better shape, but it was wrapped in varicose veins, impeding healthy development. When Glogau was 21, he was told he would not be able to father biological children. In subsequent years, his infertility would cause the breakup of one relationship. “So my wife knew from our very first date that this was going to be an issue,” he says.

Even so, as time went by, the couple began to hope. Mysti finished her nursing degree. Glogau went back to college. They tried to have a baby — and tried and tried. When it didn’t work, Adam tried all the standard medical therapies before turning himself into a “human science lab,” spending up to $250 a month on homeopathic and experimental alternative treatments to increase his sperm count. (They didn’t work.) The couple were told they could attempt intracytoplasmic sperm injection but they declined, worried that the procedure could increase the risk of birth defects or miscarriage. (Some studies have found that ICSI is associated with an increased risk of birth defects when compared to traditional IVF, but it has not been connected with increased miscarriage rates.) And the procedure raised additional questions: Did Mysti want to face the possibility of multiple births? What would happen to any unused embryos?

Ultimately, Glogau and his wife decided to foster two children with the intention of adopting, but the children needed specialist care, Glogau says. He and Mysti struggled, received inadequate support, and the relationship with the foster kids frayed and ended in heartache. Then the couple tried donor sperm, which didn’t work either. As it turned out, although Adam’s issues were more severe, his wife had fertility problems too.

Just like women, men talk of anguish when friends and relatives become pregnant easily, of feeling triggered by apparently harmless small talk, and of seeing babies and happy families everywhere. On his blog, Glogau laments that his inability to give his wife a child left him feeling “sub-human,” he writes. He describes a young man he mentors, who had children, unplanned, by two different women. “I love him dearly; I’m the godfather of the first born. But WHY WHY WHY WHY WHY can he have kids by accident and I can’t have one on purpose? There is so much that I cannot wrap my mind around.”

Despite the sometimes-devastating impact of infertility, the support that exists for men like Glogau is meager.

In 1993, British journalist Mary-Claire Mason wrote a book about men’s experiences of infertility. Mason’s own husband was infertile, and when preliminary tests indicated poor sperm quality, doctors recommended IVF, which the couple chose not to pursue because of its invasiveness and the associated risks. But Mason wanted to shed light on what it really felt like for men. She reached out to subjects through newspaper ads and publicity campaigns, offering anonymity. The respondents spoke about feeling isolated, lonely, unsupported by the medical establishment, and even ignored. Mason wrote of being struck by “how much things have not changed since the 1940s,” when male infertility was poorly understood and doctors avoided thorough physical examinations of men, instead focusing their medical investigations on women.

In a 1993 book, British journalist Mary-Claire Mason sought to shed light on what infertility really felt like for men.

The experiences of men with infertility being expressed today echo her interviews in the 1990s. “To be honest I don’t think a huge amount has happened since I wrote my book,” she wrote to Undark in an email. “I think pregnancy is seen still at heart as women’s business, not men’s so they are side-lined, all the research and services are directed to women. Which has implications for research and could perhaps be a factor in why so little is still understood about male infertility.”

Mark Cloete is 37, lives in England, and sports a moustache and a small beard, an achievement possible only after starting testosterone injections. Until recently, he lived with his girlfriend, but they broke up late last year. “Me and my girlfriend decided to go our separate ways as there is a potential she wants to go down the route of carrying a child,” he wrote in an email. “It is interesting even after entering a relationship and on the first date declaring you can’t have kids, four years later it erupts and ends another relationship.”

Cloete was previously married, but that came to an end in 2016 after a diagnosis of infertility. He and his wife had tried to have a baby, and when they couldn’t conceive, they were both tested. Cloete’s wife, it turned out, was very fertile; but the semen test revealed that Cloete had no sperm at all. Cloete said the doctor pushed the couple to move immediately to donor insemination, ignoring the shock that Cloete had just received and also failing to follow up with any investigation into the source of his infertility. Cloete wasn’t ready for assisted reproduction and needed time to grieve, but he found the doctor had no time for him.

Doctors lack subtlety in telling men they have fertility problems, says Cloete, particularly compared with what he sees as their careful and sensitive approach towards women when options, solutions, and possibilities would be aired and discussed. “It was said in such a blasé way,” he recalls. “I’ll never forget it. It was one of those moments that will stick with me forever.” (Adam Glogau recalled a similarly blunt approach: The diagnosis wasn’t even delivered by a doctor, he says, but by a nurse practitioner or assistant who was “extremely grumpy and irritable” and delivered the news matter-of-factly. “I walked away just knowing that I would never be able to make kids on my own and that was it.”)

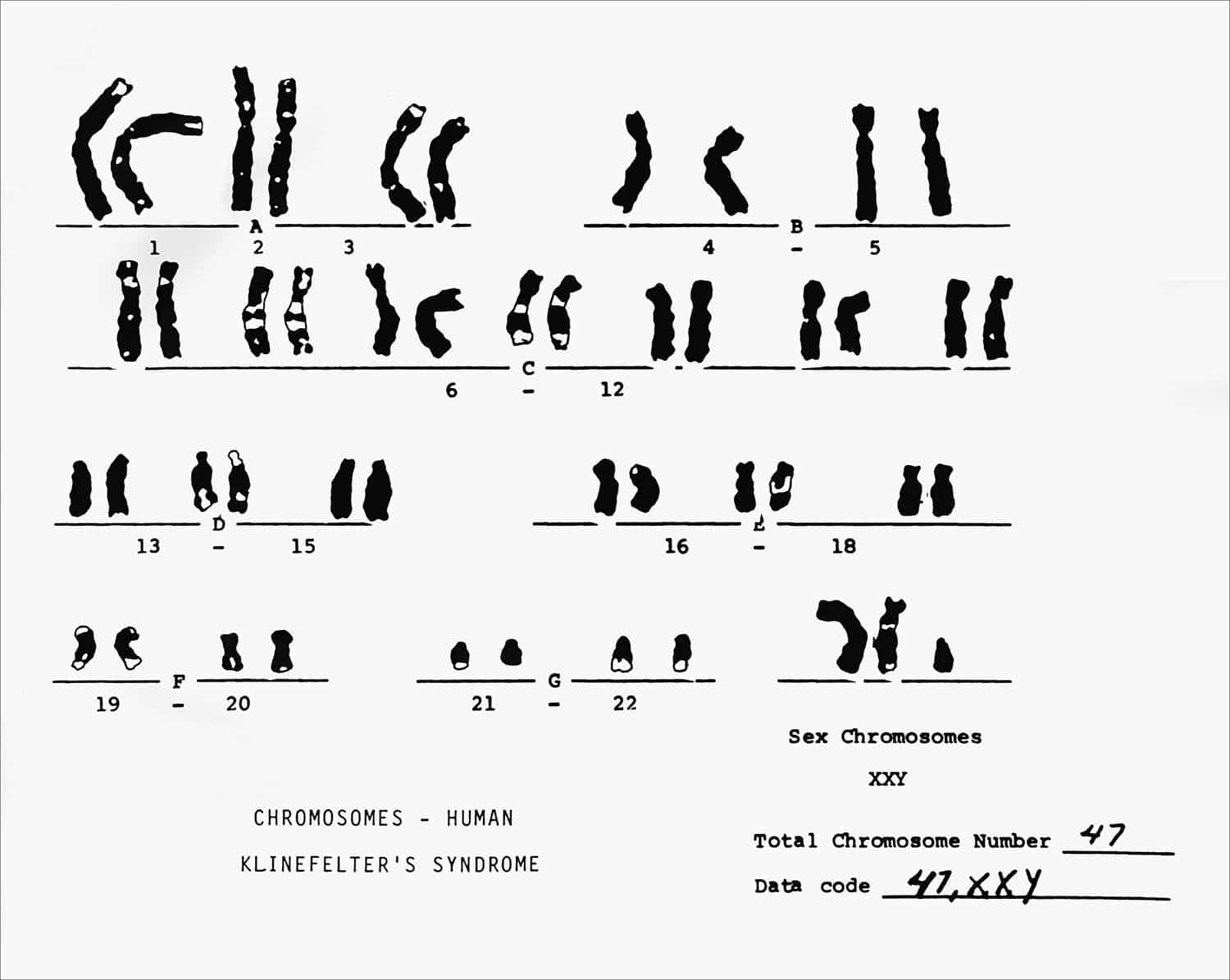

Eventually, Cloete visited a specialist, who asked him to drop his trousers for a physical exam. It was the first exam Cloete had undergone as an adult. While many women receive regular gynecological exams, men rarely have their genitals examined. “The moment he touched my testicles he wrote down XXY on a piece of paper,” Cloete says.

It meant that Cloete had Klinefelter syndrome, later confirmed by a blood test. Women usually have two X chromosomes in every cell in their body; men have an X and a Y. But men with Klinefelter’s have an extra X chromosome in their cells. As a result, they have lower levels of testosterone, and they face a host of potential health issues: an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, blood clots, depression, anxiety, type 2 diabetes, autoimmune disorders, and breast cancer. Klinefelter’s is also a leading cause of infertility where a man’s semen contains very little or no sperm (though responsible for just 3 percent of all male cases).

Having Klinefelter’s can reduce a man’s life expectancy by about two years. It takes a toll on a man’s quality of life, which is why treatment, including testosterone injections, is given to improve libido, concentration, and bone health. Although it affects one in 600 men, three-quarters never realize they have it. Those who do learn about their status are often diagnosed later in life — when they are trying for a baby.

Cloete went on to meet with a group of other men with Klinefelter’s. The overwhelming feeling was connection — and relief. “When I was telling my story, and they were telling their stories, it felt as though every time they were talking, I was talking,” he says. “Even when I think about it now, it gives me a nice feeling because it’s such a relief to hear other people have gone through the same as what you’ve gone through.”

Because of the stigma, most men with infertility seek support on the internet. In 2015, Glogau found solace in a Facebook group, “TTC (Trying to Conceive) with male infertility.” He felt the need for a safe space where men could say, “This sucks and I don’t know how to deal with this.” The group is global, with members in the U.S., Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and across Europe. Glogau soon became the group’s moderator. Supporting others helped him find a new trajectory. He began to retrain as a pastor and got involved in setting up Grace Downtown — called “the church in a bar” because of its original location in the back of a local restaurant. “We wanted to go where we would find the most broken people possible,” he says. He and Mysti also happened upon an adoption agency that matched their values.

Even on Facebook, fertility is highly gendered. Participation in women’s support groups can number in the tens of thousands while Glogau’s, which has been growing, has roughly 900 members. (A larger men’s group has just over 1,700.) Women usually join first, Glogau says; their partners’ requests pop up in his box a couple of days later. Glogau posts emotionally complex videos — angry, affectionate, despairing, and deeply honest — articulating his response to adopting a little boy, or his feelings about Father’s Day. “I’m trying to show them that they’re not alone, that they’re not the only ones struggling through this,” he says.

Last June, at a meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology in Vienna, a psychologist from Baltimore named William Petok advised a gathering of therapists on how to appeal to male clients and get them to open up. Appointment times should be convenient, he said, and counsellors should adjust their language and terminology, swapping out “feelings” for “thoughts.” Petok also recommended neutral décor for the consultation room. “You can’t have a lot of lace or pink,” he said. It’s hard to persuade men to come to therapy, he explained, and when they come as part of a couple, women do most of the talking. About 50 psychologists sat attentively in the windowless room. Most of them were women, which aptly illustrated another of Petok’s key points — a lack of male voices coming forward to talk about infertility.

To better serve men, clinicians say it’s important to recognize that boys and men have been raised with different expectations about visiting the doctor. Throughout their lives, men interact less with health care providers than women, a pattern set as young as five years old, when parents start bringing their sons less often to the doctor. This sets a trend that scientists have found lowers men’s life expectancies. By living sicker and dying younger, men steeply increase the financial burden of global health.

Given this, Turek says that if a man in his 20s does step foot in a doctor’s office, the doctor should address reproductive health. “You’ve got to examine their testicles,” he says bluntly. “You can’t not examine them” because there won’t be many other opportunities. He says that a young man coming in to discuss a sexual health problem, for example, is also a prime candidate for having his fertility tested.

Intervening even earlier could also assist some men. Glogau believes he personally could have benefitted from this kind of early, proactive medical care: “There were surgeries that could have fixed this back in the day. So people need to be aware of this in their teenager years, right after puberty. Get their children checked out.” And treating teens who have Klinefelter’s with testosterone allows for the development of facial and body hair, increased muscle mass, and a deeper voice, while retrieving sperm at a young age can preserve their fertility. But early intervention is complicated because the various treatments can cause side effects (testosterone replacement therapy may itself damage existing sperm production) and they do not guarantee positive results. Further, some interventions, such as obtaining semen samples from youngsters with varicocele or other issues, are fraught with ethical dilemmas, says the urologist Jonathan Ramsay.

In the absence of a health care model that draws men in, forums and online resources are a key source of solace and information. Research is sparse, but Glogau says the men in his Facebook group are becoming increasingly curious about how lifestyle and behavior affect infertility. On the one hand this is positive, since weight and health tie in with reproduction. But it may also point to the fact that men, hoping to avoid the medical establishment, are trying to do what they can on their own. Interest in lifestyle choices may also point to financial constraints, Glogau says, because male fertility treatments are rarely covered by insurance.

Talking openly about the experience of infertility really helps, says Raj Baksi, an advocate for the Klinefelter’s Syndrome Association living in Brighton, England. Friends often don’t know how to deal with the situation and friendships can evaporate under the pressure. In contrast, men who are in the same boat know what it feels like to be infertile. In fact, Cloete maintains that Baksi served as his “life support” when he learned about his diagnosis. He stresses that men feel sadness and grief at prospective childlessness just as much as women but are restricted in where and how they can express themselves. Facebook has been one place where men do open up, “but I don’t think they would actually ever do that in front of their partner,” says Cloete.

In her research, the sociologist Esmée Hanna has explored the roles of online communities and their particular effectiveness in helping men with fertility problems. For one thing, they connect men from all across the world, offering consolation that may be lacking from friends who perhaps don’t know what to say or who make painful jokes about “firing blanks,” says Hanna. “There’s something about the online setting that people can access any time they need it from wherever they are. I think that’s really valuable, that it allows them to come together about their experience.”

Given that men may be hesitant about accepting support, it also lies with doctors to figure out how to draw them in, says Turek. In an interview with Undark, Turek talked about the need to cater better to men’s health, citing increased suicide rates and a general lack of openness around the subject. When he’s tried to set up in-person support groups, nobody turns up, but that doesn’t mean men don’t feel as badly about infertility as women. “I have tissues in my office because people from all over the world are crying all the time because they have no sperm,” he says. “These are men. They don’t get to do that anywhere else.”

Turek believes it is clinicians’ responsibility to reach men as early as possible. “Women have gynecologists who follow them like pediatricians throughout their life, almost,” he says. “But as soon as a pediatrician signs you off at 18, there’s no place for men that’s male specific.” Turek also suggests that clinicians should do all they can to help men feel at ease. His office has a surfboard and pictures of vintage cars (which happen to be his own) on the walls.

“If they don’t have your trust they’re not going to open up. They’re sort of like wild animals,” he says. “People walk in and immediately, they say, ‘oh you’re a surfer,’ or ‘you like old cars’ — and you break the ice. You have to show them personality to get them to do this. And then they say, ‘I trust that guy.’” With research increasingly showing that fertility is a marker for general health, Turek is optimistic that this heralds changes. If, instead of being an indicator of virility and sexual prowess, fertility can be seen as a sign of wellbeing, he believes it will be much easier to encourage men to get it checked.

Though it connects with some men, such gendered language — and talk of neutral décor and convenient appointment times, surely the preferred option of many female patients too — runs the risk of reinforcing stereotypes. The male population is diverse, observes Hanna. “Pink is for girls and blue is for boys; all those things need some greater unravelling to make any progress, really,” she says.

And in pockets online and around the world, men are opening up emotionally. Some are podcasting and making films about their experience with infertility. In April, a British filmmaker released a crowd-funded documentary, “The Easy Bit,” which features six men sharing their tales of struggle with fertility. (The title refers to the idea that by donating sperm, men’s role in fertility treatment is easy and quickly over with.) In San Diego, Ryan Bregante, president of the nonprofit awareness organization Living with XXY, posts videos online about his experience and encourages those who have it to look on the bright side about their condition, aiming to overturn stereotypes. “Some men are putting their heads above the parapet and saying, ‘This is my experience,’” as Hanna puts it. “And that is hugely valuable for other men.”

Will these still relatively few voices translate into greater openness about men’s reproductive issues? Some clinicians are hopeful, seeing fertility as a subject that fits neatly into broader mental health awareness. But men with infertility spoke of an enduring stigma; some had not talked about the issue with immediate family or friends.

Jayasena, the London-based endocrinologist, is bewildered by the lack of progress. He suggests that medicine’s failure to develop effective treatments for low sperm count is “slightly embarrassing.” Jayasena and his colleagues have conducted some of the recent work connecting men’s fertility to health issues like cancer, and they are studying the link between subfertility and being overweight. For Jayasena, solutions ought to be within reach. “It’s either an insurmountable task that is unique amongst medicine — or simply that we just haven’t bothered to research and find out,” he says.

In the absence of adequate progress, scientists warn that the gaping holes in our knowledge of male reproduction will hamper our understanding of how increasingly sophisticated reproductive technologies on the horizon — stem cell therapy, gene editing — could affect the children they produce. With evidence suggesting that the quality of a father’s sperm could affect the health of his children and even his grandchildren, these are important questions.

Since that moment with the gun, Adam Glogau and his wife adopted a baby boy, and more recently they began caring for a girl in the foster system, whom they also hope to adopt. The couple want to expand their family, and Glogau says that fatherhood offers him a chance to give back, to make the world a better place. But he continues to hope that he and his wife might have a biological child. When he put the gun down that day in 2014, it wasn’t because of God, he says, “but, the fact that there had to be something I hadn’t tried yet.” Even now that he and Mysti have successfully adopted a baby, when it comes to infertility treatment, he says, “I’m still looking.”

Frieda Klotz is a journalist based in Brussels covering culture, health care, and medical innovation. She has written for publications in Europe and the U.S., including the Guardian, Irish Times, Al Jazeera America, and Mosaic Science.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Men? Don’t you mean “people who ejaculate” or “testicle havers” or “people assigned male at birth”?

I mean, trans-activists don’t say “women”, right?

Male 64 UK based. Diagnosis when 22years,nothing much known then, tried testostrogel, gor rash, itching and aggressive tenancies, mood swings, anxiety issues. Stopped taking, not taking any medication for KS since.

I am one the person that is facing the problems

I am azoospermia patient.and testicle pain problem.

Can you help me.