As another February draws to a close, so too does one of America’s most familiar winter rituals: For the past 28 days, prominent African American cultural figures of yesteryear have been extracted from the pages of history and temporarily planted in our consciousness as part of our nation’s celebration of Black History Month.

Black inventors and scientists hold a special place in this month-long celebration. People like Lewis Latimer, Madam C.J. Walker, Elijah McCoy, Annie Malone, Garrett Morgan, Mae Jemison, and others have become powerful symbols of African Americans’ intellectual capabilities — heroes who triumphed in the highly revered, male-dominated, fields of science and technology despite the long odds handed down by racial oppression. Their contributions figure not just into the story of scientific advancement, but into a larger history of racial liberation.

In elevating black inventors during Black History Month, however, it’s all too easy to reduce these complex figures to the simplest of forms — that of their contributions. We tend to forget that they were human, driven by their own individual motivations and desires. And in doing so, we miss out on a golden opportunity to understand context — of their lives and of the times in which they lived — and to broaden the power and appeal of their stories.

The reductionist view of black science history isn’t new. In fact, it was woven into the fabric of Black History Month from the very beginning — and for good reason. When Carter G. Woodson established Negro History Week, the forerunner to Black History Month, in 1926, he did so with an eye toward combatting perceptions of racial inferiority. For Woodson, history was the means by which African Americans could demonstrate their value to American society. As historian Rayvon Fouché writes in his book “Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation: Granville T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer, and Shelby J. Davidson,” that often meant emphasizing African Americans’ technological contributions over their biographies.

An example of that comes from a short announcement published in 1930 in the black-owned newspaper The Baltimore Afro-American. The segment, titled “Negro Inventor,” described a lubricating cup developed by Elijah McCoy for use on railroads and ships. In addition, the article announced that McCoy had produced 50 other patents. Nothing was mentioned about who Elijah McCoy was or why these inventions were important. The mere fact of his patents powerfully demonstrated black ingenuity and innovation — a message that carried particular significance in the Jim Crow era, where doubts about African American intellect were rampant. As Fouché notes, the fact that federally issued patents held by black inventors like McCoy and Granville T. Woods could be easily displayed and counted made them “powerful tools to destabilize concepts of black inferiority.”

Decades later, as the civil rights movement rose to its zenith, representations of black inventors and scientists became useful in a different way: At a time when black inventors were still largely overlooked by American society, the biographies of black inventors and scientists could be mobilized to inspire.

In his 1967 book “Where Do We Go from Here?,” Martin Luther King Jr. wrote that “the history books … have only served to intensify the Negroes’ sense of worthlessness.” He pointed to medical pioneers like Charles Drew and Daniel Hale Williams and insinuated that, had these figures been appropriately chronicled in American history, those feelings of worthlessness could have been avoided.

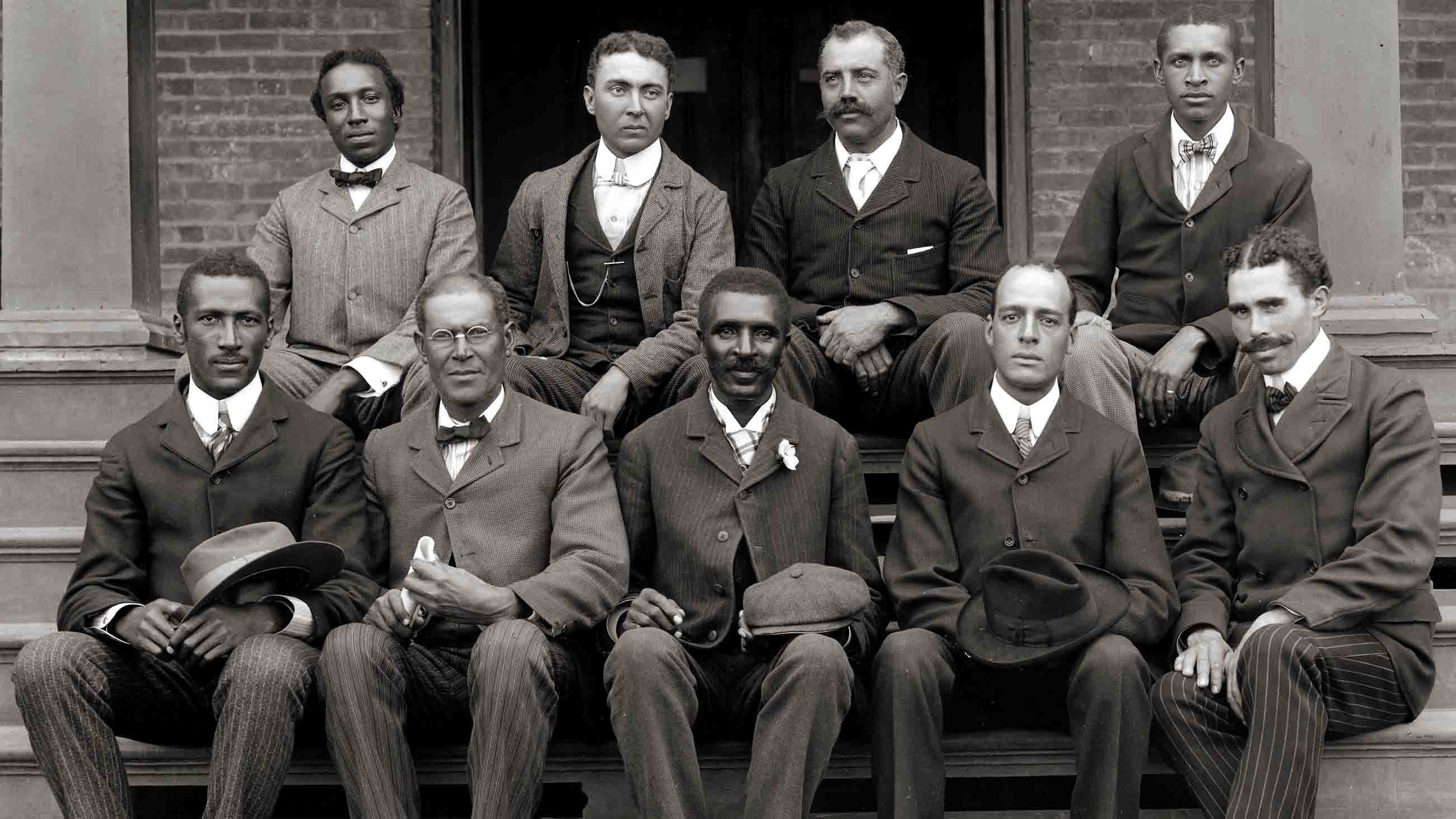

Drew and Williams were far from the only black scientists whose biographies would come to embody the twin narratives of triumph and struggle. Perhaps one of the best examples comes from Lawrence Elliott’s 1966 biography “George Washington Carver: The Man who Overcame.” In it, Elliot describes Carver’s struggles and triumphs as he transitioned from slave to one of America’s most prominent agricultural scientists. The biographer harnesses the American ideal of the “self-made man” and overlays a quintessentially African American theme of resilience.

At a moment of significant grassroots political activism, figures like Carver, Drew, and Williams offered hope. They were heroes — ideals to which the black “everyman” and “everywoman” could aspire. Such figures were necessary for black survival amid the resurgence of racial oppression and violence.

Today, the hero narratives of the 1960s have been condensed into their most compact possible form: the internet list. Sites featuring lists of black inventors from “A to Z” or the “top 10 black inventors (you didn’t know about)” reduce the canon of black scientific endeavor to a mere array of names and inventions. To be fair, the lists do a lot of work: They are effective in a fast-paced digital world overburdened with information. They are, in essence, portable amalgamations of black ingenuity that quickly communicate the breadth of African American technological contributions. But like the early 20th century representations of black inventors, the lists privilege the inventors’ inventions over their humanity.

And so it is that a figure like Carver — who was born to slaves during the Civil War, developed more than 100 uses for the peanut, sweet potato, and soybean, helped reshape the South’s agrarian economy, earned international acclaim for his work, and advised the nation’s leading politicians on agricultural policy — comes to be known simply as the man who invented peanut butter. (Peanut butter, contrary to popular belief, was not among Carver’s innovations.) By reducing Carver to the sum of his inventions, we discard many of the lessons his life could teach us.

There are signs that popular representations of black inventors and scientists in the 21st century are beginning to shift. For instance, Carver has recently been embraced not only as a black historical icon but also as an LGBT icon, bringing to light new questions about his legacy and the role of intersectional identities — and broadening his inspirational appeal. Films like “Hidden Figures” necessarily followed black women “computers” from the halls of NASA to the halls of their homes. These women triumphed not only in the face of racial oppression but also in the face of gendered oppression. And Rebecca Skloot’s “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” placed the life and monumental, but contested, contributions of an impoverished black woman at the heart of major scientific advancement in the mid-20th century. When we humanize black inventors, we see that their contributions to American society go much further than their inventions and even transcend the project of black liberation.

Our representations of black scientists and inventors over the past century have not been stable; rather, they have evolved over time to meet the pressing needs of an African American community fighting for racial equality and liberation. But it’s worth remembering that these inventors were more than the sum of their inventions. It’s worth asking who they were outside of their laboratories. And it’s worth critically examining the details and complexities of the lives they lived — and the times they lived in. By doing so, we may find new historical uses for the black inventor, and we just might breathe new life into the human beings that history left behind.

Ezelle Sanford III is currently completing a Ph.D. in the History of Science at Princeton University. His dissertation chronicles the history of Homer G. Phillips Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri. His twitter handle is @ezellesanford3.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Is very interesting. I like it!

Thank you for your work!

As with Jackie Robinson, the famous baseball player. Most of his fame centered around his skill of hitting/running on the baseball diamond. But HOW he related to his teammates and other players reflected in his humanity. As a military man he had to deal with discrimination. There is the incident where he was ordered to get off a bus because of his race. And he was an OFFICER. Can you imagine the Twitter messages he would get from bigots if that worthless communication medium had been invented back then!