A Little Less Science for EPA’s Science Advisory Boards

Revelations about relationships between industry and the Trump administration officials, and how they relate to policy, are emerging almost weekly. Those ties could grow even more complex and consequential with the reshaping of independent advisory panels that recommend public health standards on everything from ozone pollution to pesticide exposure.

The Environmental Protection Agency in particular has been culling scientific advisers, worrying many in the scientific community that the Trump administration intends to replace their voices with industry-friendly ones. More recently, agency officials have taken an axe to EPA’s Congressionally-mandated Scientific Advisory Board and its subsidiary Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee.

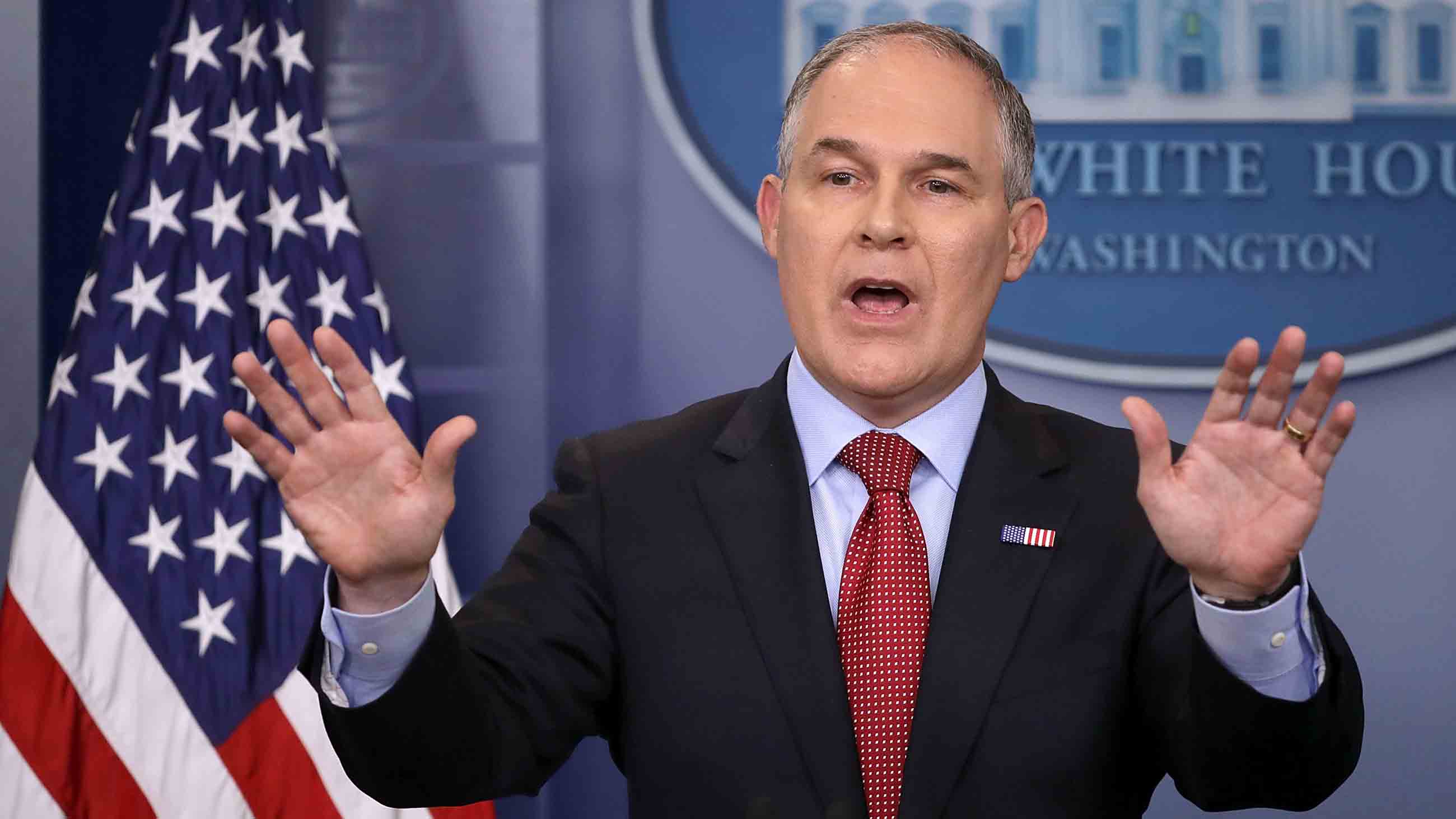

These advisory positions — often (though not always) unpaid — are influential in their ability to offer input on EPA rules, and members have traditionally been drawn from academia and the wider scientific and research communities. But in an announcement late last month seeking nominations for new advisers, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt expressed interest in “scientific viewpoints from a full range of stakeholders” — a phrasing that many observers took to be an open call for nominations of industry representatives.

The announcement also pointed explicitly to a recent Government Accountability Office report, which found that EPA’s Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC) “has never provided advice on adverse social, economic, or energy effects” of air pollution standards. “Moving forward,” the agency’s statement declared, “EPA will ensure the CASAC addresses this serious deficiency and fulfills its complete duties.”

While the administration has decried the financial costs of regulations on industry, environmental advocates note that the federal standards-setting process calls for protecting the public health first. Regulators then consider cost and technical capabilities to meet the standard through policy and risk and exposure analyses. Opening the scientific process to industry and state regulatory input would invite conflicts of interest, critics of the recent EPA moves argue — potentially allowing them to insist on weaker limits.

“We’ve heard those arguments before and essentially our response remains the same: The Clean Air Act says to consider public health, period. You don’t consider the cost,” Janice Nolen, assistant vice president of national policy with the American Lung Association, told Undark.

Nolen and other critics point to other worrying signs, including deep ties between industry and the administration’s government-wide deregulatory effort. A top scientist on the agency’s scientific review board has also publicly said that Pruitt’s chief of staff tried to influence her testimony at a Congressional hearing. Other reports have documented meetings between administration officials and business leaders preceding regulatory decisions that favored those firms. And a former American Chemistry Council official now at EPA reshaped a chemicals law to benefit industry clients for which she used to lobby.

At the same time, some stakeholders welcome a shakeup of the EPA’s science advisory boards because they say the panels are bereft of expertise in the actual implementation of environmental regulations and the social and economic impacts that come with them. Quite aside from industry representatives, that sort of expertise can be delivered by local, tribal, and state environmental regulators, said Clint Woods, executive director of the Association of Air Pollution Control Agencies, whose members are state and local air regulators.

“You have a fairly clear directive from Congress that you want to have diverse perspective,” Woods told Undark. “I would not undersell state environmental regulatory experts.”

Woods’ group is launching a website next week at www.cooperativefederalism.org, which he called a “one-stop shop” for his members to find out when and where federal advisory committees were meeting. Woods said the goal of the website, which is currently in a pilot run, is to enable state, local, and tribal officials to more easily make their voices heard.

The ongoing battle regarding standards for ground-level ozone, or smog, is perhaps the most instructive example of what’s at stake. The EPA delayed the Obama administration’s 2015 proposal to tighten the standard, arguing that states needed more time to craft implementation plans.

Industry, along with GOP-leaning states, contend that the new, tougher emissions standards would cripple manufacturing, and Congressional Republicans have long cited the ozone standard as a reason for overhauling the EPA’s advisory boards — an argument that Woods happens to agree with. He noted that of the 22 members on the science panel working on the ozone standard, just one came from a state or local perspective.

But public health and science experts are concerned the Pruitt-led EPA is less interested in a diversity of voices for its own sake, and more committed to simply convoluting the rulemaking process by including industry voices and state officials who might well be influenced by economically important businesses they regulate. That the EPA delayed implementation of the new ozone standard even though many states would have had to do very little — or in many cases, nothing — to meet the new limit sets a troubling precedent, environmental advocates say.

“We’re concerned about every step of the process,” Nolen said of the ozone standard process. “Including who reviews it.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

It’s not the scientists job to analyze implementation, it’s to determine harm. There are comment periods before regulations take effect. Industry can suggest costs and plans during this period along with cost analysis so the argument that they are not discussed is specious and misleading.

School test scores were higher in southern California prior to clean air rules. one has nothing to do with the other yet I’m sure someone will use it as an argument for orange skys. Is the fact that peoples health is improved more or less offset by the enormous costs?