Can the Airship Rise Again?

There is something romantic about the persistent dream of the airship, those lighter-than-air crafts, sometimes called dirigibles, that companies have tried for decades to turn into a commercially viable means of ferrying passengers – or freight – around the world.

Last month, in what was really just the latest in a steady supply of news articles highlighting efforts to rekindle dirigible transport in recent years, the New Yorker magazine spoke with several airship companies that, with new technology and new funding, are once again angling to turn their lofty dreams into reality.

Strangely missing from that story — which highlighted the efforts of blimp enthusiasts to solve longstanding problems like high winds and, arguably more nettlesome, high costs — was the fact that helium, the gas typically used to get these behemoths aloft, is an unstable, pricey commodity that cannot be manufactured.

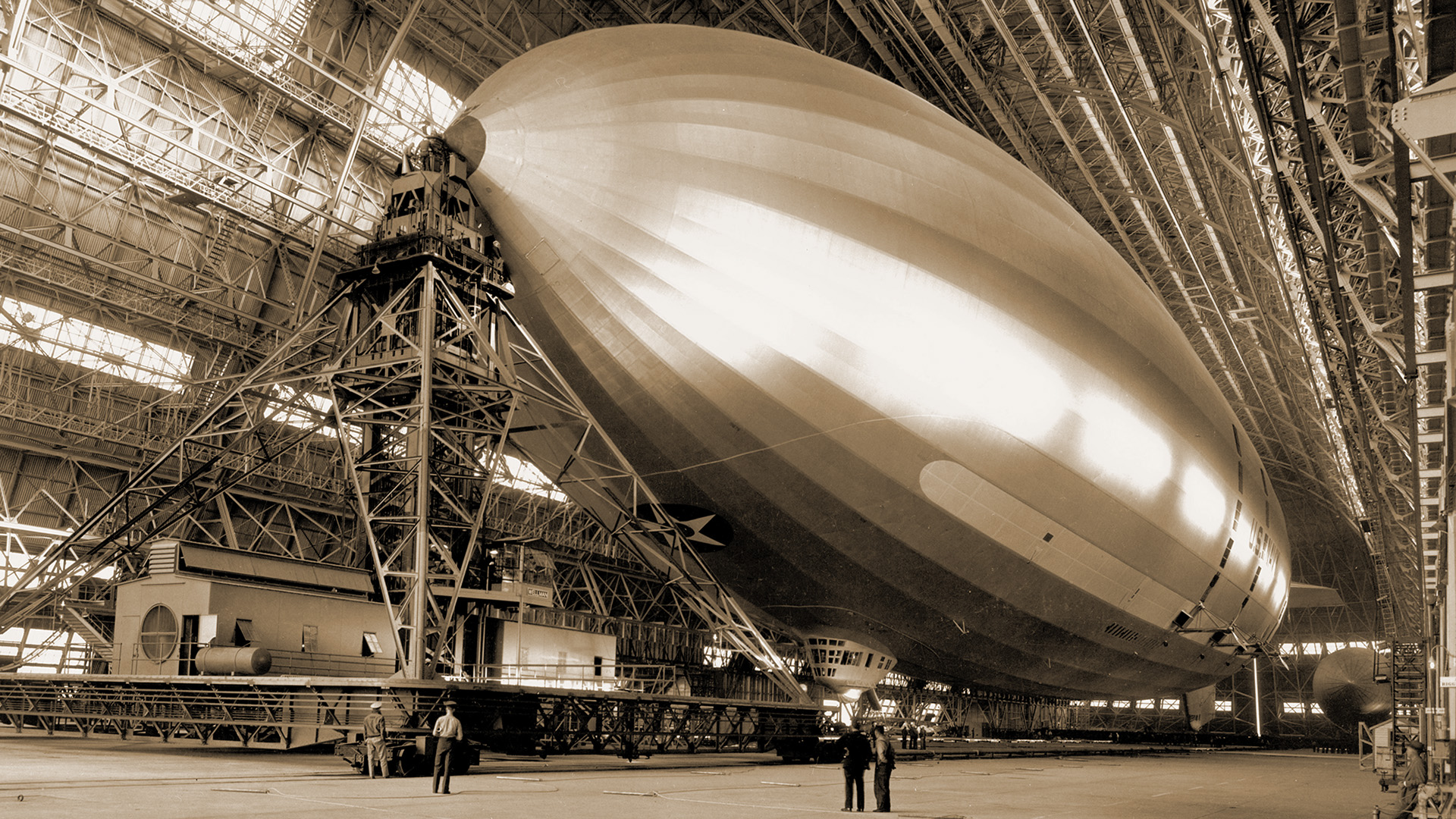

The infamous Hindenburg airship used flammable hydrogen for lift. Helium, while more scarce, is non-flammable. Visual: Flickr

In 1996, when the U.S. decided to sell off and close the world’s largest helium reserve in Amarillo, Texas – a site capable of storing helium and buffering global fluctuations in its supply – prices rose and the industry went into upheaval.

“For a while you couldn’t even get helium for your party balloons,” said Brandon Buerge, who teaches aerodynamics engineering at Wichita State University and is a consultant to the airship industry.

It’s not that the world is running out of helium, Buerge noted. It’s that helium is by its nature a volatile market. It’s got built-in scarcity, wide geographic variability in its abundance and quality, and wild swings in supply and demand.

Funny, for such an inert gas.

Today, the concerns over short supply have mostly been alleviated. That’s because the imminent shuttering of the U.S. government’s Amarillo site — and the resulting hike in the price of helium — has made room for new players.

“There are new sources that are either on-stream or ramping up,” said Tim Parker, operations product manager for helium supplier Airgas. With the U.S. government’s departure and higher prices making helium more profitable, producers new and old are getting into the game, he said. “As the cost of helium continues to escalate, there will be opportunities to mine for helium that weren’t previously economical. People are going back to old wells.”

Still, others warn that the helium market won’t lose its volatility — especially as new, less reliable producers come online in countries like Qatar, Russia, Poland and Algeria.

And that will continue to present a hurdle for dirigible enthusiasts who hope airships will one day replace the shipping infrastructure that clogs the world’s highways and waterways. Moving freight by blimp, they argue, is a potentially lucrative industry that would solve the inefficiencies of shipping cargo by road, rail and sea. They also note that, compared to conventional, fossil-fueled air cargo, dirigibles can carry significantly more freight with less crew, fewer planet-warming emissions, and little in the way of ancillary infrastructure (think long ribbons of asphalt tarmac and other necessary ground-based sprawl).

That sounds great, but one other hitch, aside from fickle helium supplies, in the age of Amazon.com: Dirigibles are mighty slow. Although some specimens likely moved faster, the swiftest airship ever officially recorded, according to the bookkeepers at Guinness, was just under 70 mph. That’s compared to speeds of roughly 300 to 500 mph for a typical cargo jet.

This means airships will have to find their niche in very specific shipping markets — and they’ll have to prove that they’ll be cost-effective just the same.

That part might not be so difficult, depending on the circumstances.

With refined helium price costing around $30 per hundred cubic feet, filling an airship the size of the Goodyear blimp could cost in the $75,000 range. Filling Lockheed Martin’s LMH-1 could cost $390,000. And filling a behemoth like Hybrid Air Vehicles’ proposed Airlander 50 could cost almost one million dollars, accounting for room left for the lifting gas to expand as those airships climbed.

While these numbers seem steep, the vehicles only need to be topped off occasionally, said Airgas’s Tim Parker. And unlike crafts running on jet fuel and related products, airships can run for years on a single fill-up of helium.

“Blimps generally consume very little helium,” said Parker, describing how Goodyear occasionally calls up a company like Airgas to request a couple of tanks of helium to top off the blimp. “It’s just a little bit of maintenance, that’s all.”