To Address Flooding in Miami, the Best Way Forward Might be Back

After a day or two of heavy rain, Marvin Ramsey starts shooting worried glances out of his front window. Heavy rain is a fact of life in North Miami, so he does this fairly often. But it’s when the storm drain across the street starts backing up that Ramsey knows he has a problem.

Two municipal pumps usually push the water uphill, into a canal and out of mind. When they don’t, Ramsey calls up Miami-Dade County to let them know the pumps have broken. Outside, he puts sandbags around the base of the house, and starts bailing with his private collection of electric pumps. Then he gets everything inside — couches, computers, everything — up on cinderblocks and off the floor.

With Hurricane Matthew bearing down on south Florida, the hard lessons of the region’s geography might once again be on display.

Visual by iStock.com

Ramsey, a retired corrections officer, owns the lowest house on his block — part of a majority black community where 26 percent of residents live below the poverty line. He is a grandfather of three and likes to go drag racing and fishing. He just finished paying off this house, which he estimates has flooded 15 times since he bought it in 1994.

“It’s pretty much traumatized my wife and my 18-year-old daughter,” Ramsey said. “To live like that is something I have to apologize to them for. We didn’t want to move, and we thought things were going to be better.”

In recent years, residents from Ramsey’s community have applied for buyouts from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to escape the repeated flooding, but those applications have yet to be funded.

This is life on the front lines of climate change in Miami, where residents and urban planners alike searching for new ways to cope. With rising seas and a warmer atmosphere fueling heavier rainstorms, the city’s water management system is forever struggling to keep up, and that system will be challenged again in coming days with the arrival of Hurricane Matthew.

It is a problem that’s been long in the making — and one that researchers like Ryan Vogel say will require creative thinking to fix. In 2014, while working as a researcher at Florida International University, Vogel paddled 23 miles in a kayak from the Everglades down the Miami River, through downtown Miami and at last into Biscayne Bay. He had charted his course using old city maps in search of the original paths of primordial wetlands.

What he saw on his trip was sobering. Almost the entire route had been dredged, widened, dammed, and crisscrossed with bridges. Where water used to seep through the landscape, it was plunging toward the sea as through a chute. “Any historical plants or trees were destroyed,” Vogel said, “and much of the geological formations alongside these routes have been disturbed.”

Prior to the 20th century, a heavy rain in South Florida meant that water would overflow the southern ridge of Lake Okeechobee to spill down into through Everglades. Then in 1928, a hurricane punched a wall of water over the inadequately reinforced southern rim of the lake, killing thousands of mostly black farmhands. (The event is recounted in Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God.”)

In response to that storm and another in 1947, the Army Corps of Engineers spent two decades developing a system of canals, levees, dams, and spillways to control the water. That process dried out the Everglades, causing an ecological catastrophe that may never be reversed. But it did also succeed in stabilizing South Florida’s tendency to seesaw between drought and flood, and made the environment more predictable for farms and suburbs.

This system is the legacy left to the South Florida Water Management District, which manages water on a scale similar to that of the entire country of the Netherlands. And now that half-century old infrastructure is under threat from climate change, confirms Jayantha Obeysekera, chief modeler for the district.

Since the Army Corps of Engineers built the system, seas have already risen 5 or 6 inches. “If you look at their documents, there’s very little attention to sea level rise that should be incorporated into their designs,” Obeysekera said. “The past sea level rise is making management of the coastal infrastructure very challenging.”

Miami’s infrastructure won’t be getting a break anytime soon. The city is already locked in for another 6 to 12 inches of sea level rise by 2030, according to Ben Kirtman, a climate scientist at the University of Miami. This can’t be avoided even if we lower carbon emissions, he said. “What’s going to happen over the next 15, 30 years or so is already baked into this part of the physical system.”

As the oceans warm, thermodynamic logic dictates that the water expands. Warmer weather is also melting ice caps, which raises water levels further. And climate change tends to make the Gulf Stream sluggish, backing up more water along Florida’s east coast.

There, unique geology compounds the problems. Miami’s rising seas can’t be held at bay by bulwarks of concrete or enormous pumps. The city sits on a sponge cake of limestone, the buildup of ancient coral reefs and chalky shallow seas, which is so porous that it allows seawater to keep coming up from beneath. Miami’s paved-over wetlands are guaranteed to face an invasion of salt water from the east.

Also, crucially, climate change’s long-term impact on the rain forecast is uncertain. If rain increases 10 to 20 percent, as some models show, low-lying areas will face even more flooding, and the canal system could be overwhelmed.

This year’s El Niño offered a preview of that potential future. Rainfall was so extreme this past winter that the South Florida Water Management District had to discharge water from Lake Okeechobee, and as a consequence, the nutrients washed out to sea led to algal blooms along the Florida coast.

Alternatively, the climate modeling tools favored by Kirtman show rainfall may instead decrease by 10 to 20 percent while the ocean rises. If this happens, the Everglades will wither, groundwater tables will fall, and that underground wedge of salt water will press inland like an advancing weather front.

Ramsey is one of those at the mercy of the strain on the obsolete infrastructure, but he didn’t understand exactly why the flooding kept happening in his part of town.

It finally clicked this May, when New York-based landscape architect Walter Meyer gave a presentation at a local community center. Along with his wife, Jennifer Bolstad, Meyer teaches at the Parsons School of Design and runs a firm called Local Office Landscape Architecture in Brooklyn.

This year, Miami-Dade County invited Meyer and the Urban Land Institute, a nonprofit that focuses on land use and infrastructure, to study the Arch Creek Basin: a former drainage area split into a patchwork of unincorporated communities and pieces of four cities, including Ramsey’s neighborhood.

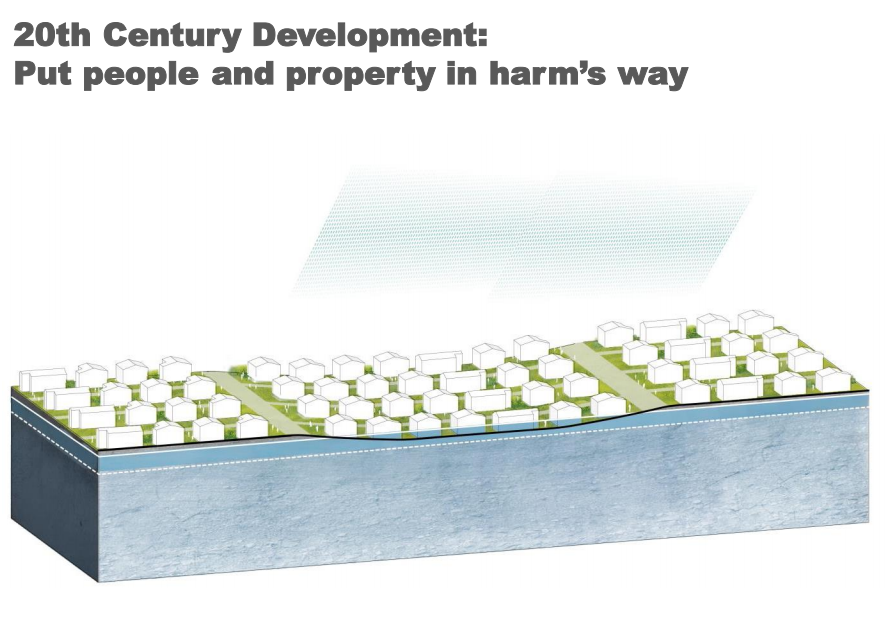

The issue, Meyer explained in his presentation, was that a series of west-to-east wetland channels called the “transverse glades” used to connect the Everglades to the Atlantic. Until they were filled in and built over, they sliced through what would become the Miami metro area like horizontal stripes.

Ramsey saw that his neighborhood was built exactly over where one such channel used to run. The city was a palimpsest, where an artificial, rectilinear pattern had been stamped on top of an older, natural grid.

It was enlightening but frustrating, Ramsey said. “My thought was, ‘Why did you let us continue to build if you knew about this issue years ago? Why didn’t you just start making the canal, or an exit for the water, the way it would naturally run?’”

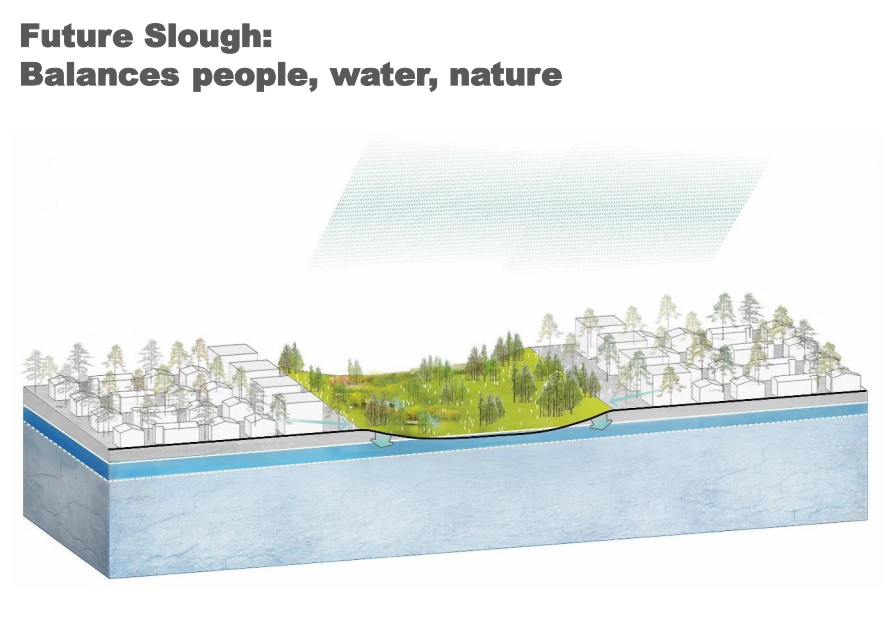

And then Meyer showed them the panel’s proposal to do just that: Where sloughs used to run, the best way forward might be back. Block by block, you could bring back the wetlands.

The idea, to be written up in a ULI study with a planned November release date, is to pick a flooding-prone inland area of three east-to-west blocks of perhaps a hundred homes. The lowest central block would be converted into what Meyer dubs a “city slough,” an artificial wetland that could hold onto water. Denser townhomes would be built on the two blocks to either side, allowing residents in the middle to swap their houses for uphill accommodations.

That would prevent flooding, provide a park for people and a more natural ecosystem for wildlife, and help fresh water percolate into the ground where it could fend off the saltwater advancing on well fields underneath. Eventually, if the pilot were to succeed, the new slough could be extended out to the east and west. Perhaps the same thing could be done for Miami’s other paved-over channels, replacing the hydrological function of the historic transverse glades with what Meyer calls the “Metro-glades.”

Meyer and Bolstad call their approach “forensic ecology.” “It’s not a study in nostalgia,” Meyer said. Instead, the idea is to build artificial environments that recapitulate what nature was doing well before.

It could help extend Miami’s lifespan for decades, until changes in global policy can tackle the carbon emissions causing this problem in the first place.

“What we’re doing now is simply buying time for the most vulnerable parts of the county with these sloughs,” Meyer said.

At the state level, climate change policy in Florida is stagnant. Even the words “climate change” are reportedly off-limits in the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. But in southeast Florida, where sea level rise is a nonpartisan reality, four counties containing over 5.5 million people have banded together to form an organization called the Climate Compact. Miami-Dade County even has a Chief Resilience Officer: Jim Murley, who invited ULI to Arch Creek in the first place.

Even so, that doesn’t mean the city sloughs pilot plan will immediately go into action when published in November. “There are so many caveats, I’m afraid,” Murley said. “[Meyer’s] ideas are very exciting. But they can’t be done overnight.”

In November, urban designers and architects plan to meet to brainstorm how the ideas might be implemented. Once the project has a budget, they’ll have to look for funding services and permits, Murley said. And then the city will have to speak with communities that might be open to such a move, like Arch Creek residents and Marvin Ramsey.

But it’s an attractive strategy to go with the area’s natural hydrology instead of against it, Murley said.

Kirtman, the climate scientist, agrees. Restored wetlands will help by holding on to fresh water instead of dumping it into canals. “I think that’s unambiguously a good idea,” he said. “Adaptation requires the recognition that some parts of where we have developed, and where people have built homes, are going to have to be returned to the natural environment to increase our ability to store water.”

This past June, three scientists from The Nature Conservancy met south of Miami, where a branch of the artificial Black Creek Canal meets the ocean. On one side of the canal is a wastewater treatment plant that serves over half a million people. On the other is a landfill. The only thing standing between either and the rising sea is a thin strip of sickly mangroves.

“The healthier these mangroves are, the bigger they are, the more branchy they are — the better job they will do of slowing down breaking waves,” said Chris Bergh, TNC’s Director of Conservation in South Florida, as he sloshed along a narrow path through the tree-filled swamp toward the ocean.

This was a scouting trip for Bergh and his colleagues, who are working with engineering firm CH2M Hill and Murley’s office to restore the ecosystem. The path they found was littered with human detritus: couch cushions, a shopping cart, somehow an entire abandoned white Mitsubishi. The chirps of Cuban tree frogs, an invasive species in Florida, filled the air.

But these are just superficial problems. Here, too, the real issue is from well-intentioned engineering projects that have wrecked the area’s hydrology. Thanks to the adjacent canal, rainfall that should be watering this ecosystem gets flushed out to sea instead. And decades ago, Bergh said, engineers cut ditches into this swamp to drain it faster, removing mosquito breeding grounds and letting in fish to eat the larvae.

Bergh and his collaborators plan to abstract the area with mathematical models, quantifying how high a storm surge could be resisted by a restored version of the ecosystem. Eventually, if stakeholders like the water treatment plant can be convinced, the ditches will be filled back in, allowing the area to hold on to fresh water.

The scientists never made it to the ocean, finding their way blocked by thicker and thicker vegetation after about half an hour. But on the way back, Bergh followed a stream to the side, where the claustrophobic path opened to a wide expanse of stunted, 2-foot-tall red mangroves, their roots in a few inches of salt water — the hump of the landfill low to the south. Here, a living seawall could thrive if water flows the way it used to.

Back in North Miami, Marvin Ramsey is going through the same calculus, thinking through the same sacrifices. “I can move this house up 7 feet, but with the water rising in 10, 15 years, where am I going to be? Where’s the neighborhood gonna be?”

“What is it somebody said — the best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago,” he said. “And the next best time is now.”

Joshua Sokol is a freelance science journalist based in Boston. His work has appeared in New Scientist, The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal and elsewhere. He earned his master’s degree in science writing from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Such nostalgia…