For Low-Income and Minority Americans, Oral Care Continues to Suffer

Two of America’s top government health chiefs of the past 30 years are opening their mouths to save yours.

“Drive-by dentistry, delivered out of a van, need not be the solution for the isolated poor.”

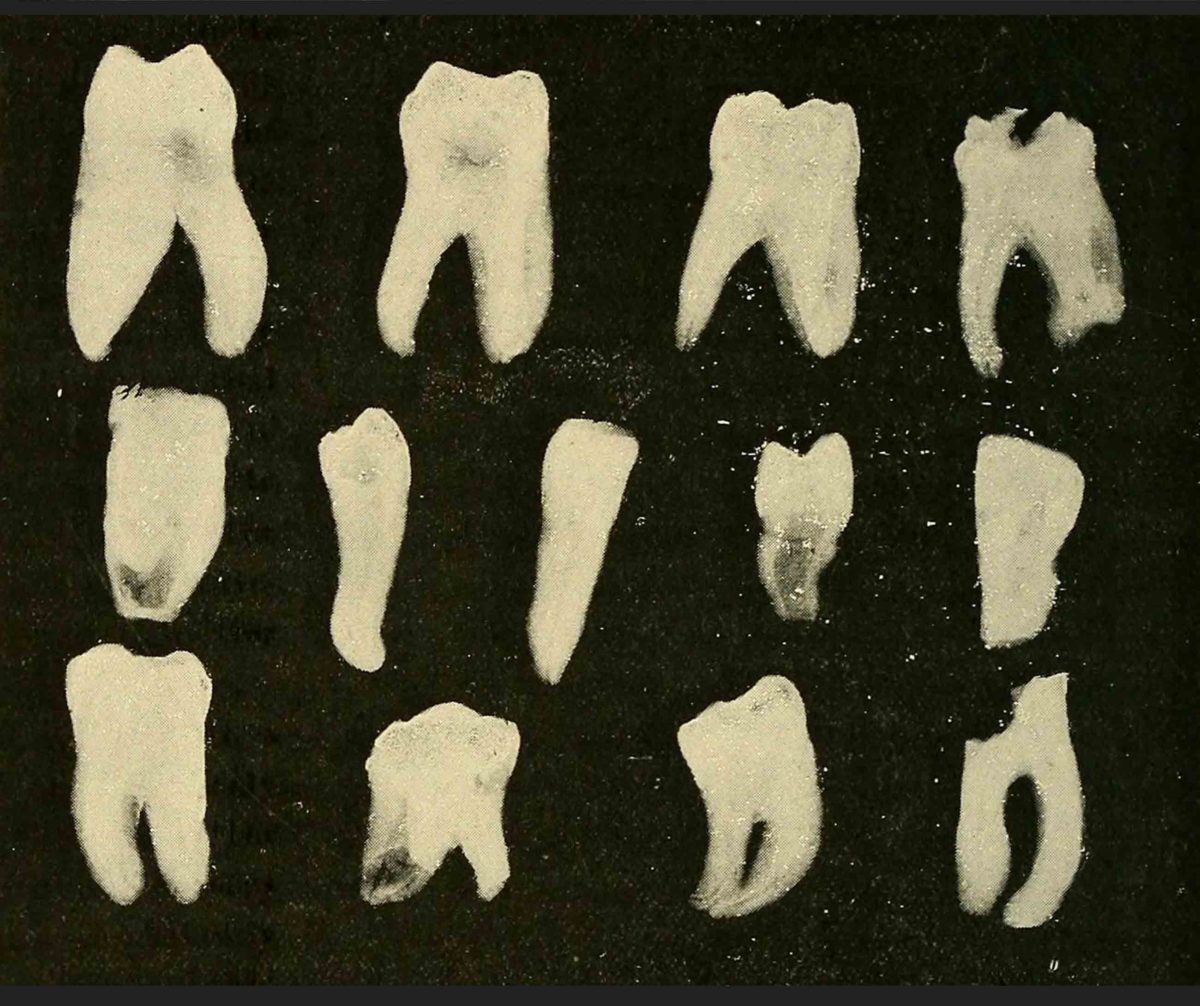

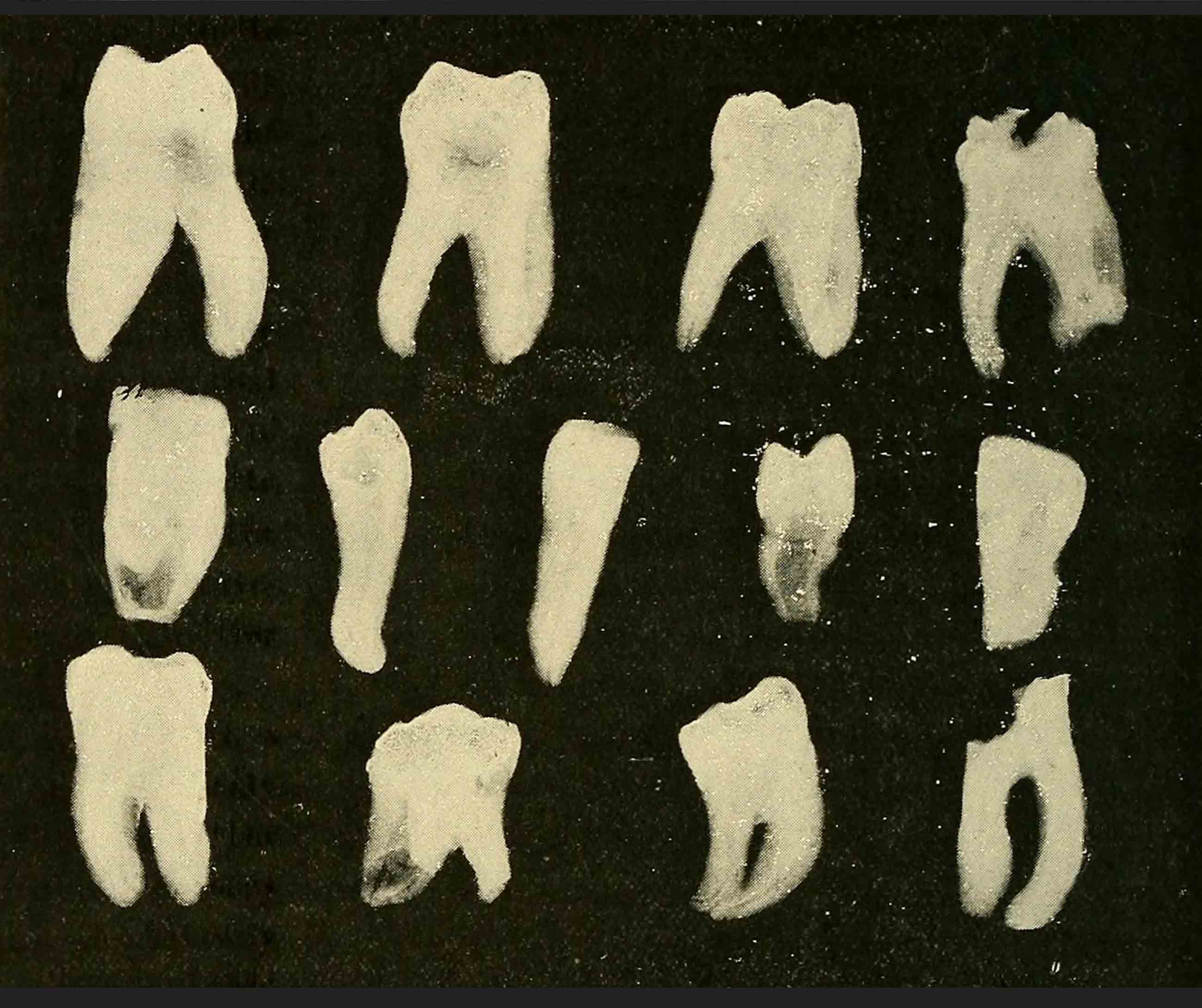

Visual: Internet Archive

For more than two decades, a clean bill of health for Americans’ teeth, gums, and surrounding tissue has been a priority for former Surgeon General Dr. David Satcher, who served during the second term of President Bill Clinton through the first year of President George W. Bush’s administration. Some of the inequities and disease trends that he brought to the nation’s attention for the first time with his “Oral Health in America” report in 2000 persist today. Satcher now spends his days as the senior advisor to the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

His colleague Dr. Louis Sullivan sees oral health in a similar light. There has been progress in the past 50 years in reducing tooth decay, but oral disease remains the most common chronic condition in children and adults, wrote the former Secretary of Health and Human Services, who served during the administration of President George H. W. Bush, in the June issue of the American Journal of Public Health. Sullivan currently is the chief executive officer of the Sullivan Alliance to Transform the Health Professions, based in Alexandria, Virginia.

Both Sullivan and Satcher call for policy changes to bring comprehensive oral healthcare to all Americans as part of a commitment to our general health.

Pervasive problems with oral health are unsurprising given the state of dental care coverage in the U.S., which far surpasses in numbers our shortage of medical insurance. A total of 130 million Americans lacked dental insurance as recently as 2009, according to the National Association of Dental Plans. Without help paying for the high cost of preventive cleanings at a private dentist’s office, let alone treatment for decaying teeth and gum disease, many people skip visits to the dentist. Over time, a social price for oral disease compounds. In a 2014 essay, journalist Sarah Smarsh explored the prejudice and other cultural messages that come with “poor teeth.”

America has yet to digest the primary message of Satcher’s 2000 report — that oral health is integral to overall health. Research links infected and decaying teeth and gums with such conditions as cancer, heart disease, stroke, sleep disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, pneumonia, and pancreatic disease.

The Surgeon General’s report detailed social disparities in oral health, which Satcher reiterated and compared with more recent figures in an essay in the same issue of the journal. For instance, poor children were found in the 2000 report to suffer twice as many cavities as did their better-off peers. And they were more likely not to get fillings or other treatment for rotting teeth. The essay also cited a 2004 report that found that black men were nearly twice as likely to have untreated dental problems and one and a half times more likely to have missing teeth than were white men.

Parallel racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic trends show up in more contemporary stats, Satcher noted. Nearly half of Americans aged 30 years or older suffer from gum disease, which disproportionately affects Hispanics, black people, Asians, and people of lesser means and lower education, according to a 2015 study. In a 2011-2012 government survey of Americans, 27 percent of adults ages 20 to 64 were found during that time to have untreated tooth decay. The rate was higher for Hispanic and black adults compared with non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic Asian adults in the same age range.

Satcher’s 2000 report noted dental coverage for all Americans as a solution. Then as now, Medicaid covers oral health care for millions of low-income people, but many dentists refuse to accept Medicaid patients, Satcher says. That leaves this population with few palatable options. As Henrie Monteith Treadwell wrote in the same issue of the journal, “Drive-by dentistry, delivered out of a van, need not be the solution for the isolated poor.”

The Affordable Care Act of 2010, which describes dental care as an essential benefit for children 18 years and under, did help to deliver routine dental care — and dental insurance — to a wider population of children under Obama. But “we still don’t have good insurance coverage for oral health care,” Satcher says. And the long-term future of the Affordable Care Act remains unclear under the nation’s current political environment.

Satcher supports Obamacare as a practical matter, but says he would prefer single-payer healthcare, like an expansion of our Medicare system that currently serves the elderly. Such an expansion would also cover visits to specialists who treat the entire body, including the mouth. “I’m not saying that as a political person,” Satcher says. “When I talk about single-payer, I’m for whatever system is going to get the most people the most care.”

But Satcher’s main concern is the oral health of children, which he learned about from direct experience. “I suffered greatly in college because I had decaying teeth,” he says. “We can’t afford to let our children go through that experience.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Scare tactics as part of marketing strategies dont help either. My dental plan resides 10,000 miles/24 hours away. I rely on herbal remedies until I can get there. My airfare, plus stay, and maybe some shopping, will all add up to the expense needed for treatment here!

Recent visit to a dentist was an amazing diagnosis for fifty dollars. She scared me by promoting the urgency of getting the “root canal done today itself, otherwise it will hurt more on the weekend. Two caps … dont get it done in that country, they leave tools in the mouth. Our treatment is good for 15 years, there’s no guarantee for their treatment lasting till your next trip.” Two months later, I am still pain free and researching other ways to management. The oath is more hippocratic to enable the doctors to buy mansions, besides their ranches and feeding herds of deer.

Most Americans have fluoride pollution deliberately dumped into their public water supplies. There is no credible evidence that taking fluoride in water has ever prevented a single dental cavity. The forced-fluoridation fanatics often try to claim that the low rates of dental caries in western European countries which do not have artificially fluoridated public water supplies are due to naturally occurring fluoride in water, or some other kind of artificial fluoridation such as salt fluoridation. They are lying. They also rely on studies which do not measure individual fluoride exposure, are not randomised, are not blinded, do not properly account for confounding factors, are highly prone to systematic error, and are typically funded by corporations such as Colgate-Palmolive.