Jerry Jones Is Right: Science Is Lacking on C.T.E.

Earlier this month, the National Football League, for the very first time, publicly acknowledged what they and others describe as a clear link between football and a progressive brain injury known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or C.T.E. Some observers compared the admission to tobacco companies acknowledging a link between cigarettes and lung cancer.

But Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, called the link “absurd,” according to The Washington Post, and he demanded more data. From the article (quoted verbatim):

“We don’t have that knowledge and background and scientifically, so there’s no way in the world to say you have a relationship relative to anything here,” Jones said. “There’s no research. There’s no data…. There’s no data that in any way creates a knowledge. There’s no way that you could have made a comment that there is an association and some type of assertion. In most things, you have to back it up by studies. And in this particular case, we all know how medicine is. Medicine is evolving. I grew up being told that aspirin was not good. I’m told that one a day is good for you…. I’m saying that changed over the years as we’ve had more research and knowledge.”

It would be easy to dismiss the rambling discourse from an N.F.L. team owner as being purely self-serving — an effort to protect the bottom line by casting doubt on the science underlying a fatal neurodegenerative disease that could deeply change football as we know it. There is evidence, after all, that repetitive brain injury may be linked to depression, confusion, dementia-like symptoms, and in some cases, suicide in some former football players.

Autopsies of these athletes show substantial devastation of brain tissue and an accumulation of neurological tangles and clogging proteins – pathologies conspicuously similar to the hallmarks of other neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. This brain damage must be caused by repeated blows to the head, some scientists have reckoned.

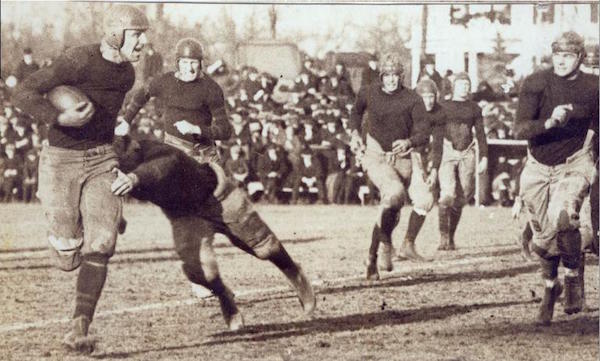

University of Maryland vs. Johns Hopkins football game in 1919. Visual by University of Maryland Libraries.

But is Jones wrong? Not about the paucity of studies on C.T.E., and not about what actually causes the degenerated tissues in these former athletes’ brains. Researchers who look at brain injury, it turns out, are divided on these issues.

“We’re talking about an ‘unconsensus’ here,” said Douglas Smith, director of the Center for Brain Injury and Repair at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. “None of these things are linked yet, but everyone feels that they are.”

One of the most troubling issues with C.T.E. studies today is selection bias, Smith said, meaning that the studies finding C.T.E. in the brains of deceased football players are limited by the singularity of their samples: That is, the brains of deceased football players. The sample size needs to be more representative of the general population, Smith said, in order to draw firmer conclusions. Studies based on the brains of athletes who committed suicide, he added, are even more limited in what they reveal about the disease and its connection to sports-related trauma.

“The problem with concussion is that when a dramatic life-changing event occurs and [an athlete] commits suicide, those are the brains that are looked at.”

If C.T.E. is indeed caused by repeat concussions, as the early evidence suggests, studies need to be designed that look at other populations, Smith said. What about non-football players who have experienced repeat concussions, for example?

“We have very high functioning, captains of industry with repeat concussions,” Smith said. Do they have C.T.E.? Researchers just don’t know.

The bottom line is that only more research will tell if concussions are linked to C.T.E., as Smith concluded in his 2013 review published in Nature Reviews Neurology. “Considerable work needs to be done,” Smith wrote, “to clearly define C.T.E. as a disease entity both pathologically and clinically.”

“We don’t have great epidemiology yet,” he told Undark in an interview. “That’s one of the main things we have to work towards.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

This study was pretty interesting and suggestive, though: http://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/mayo-clinic-cte-fl-release/

Chris, thanks for the link to the Mayo Clinic press release. The problem with these kinds of studies, Smith would point out, is that they’re filtering based on history of playing a contact sport to begin with.