Chile’s Salmon Industry Is Being Strangled by Algae

Earlier this year, warming ocean waters off the coast of southern Chile spurred an algal bloom that devastated salmon farms lining Patagonia’s picturesque fjords.

But what has international fish buyers most worried — and stock prices tumbling — is that the algal bloom appears to be ongoing. Salmon growers are still tallying their losses, and as of this week more than 20 million fish, representing 15 percent of Chile’s total annual salmon production, have been asphyxiated, or perhaps poisoned by the blooms (the jury is still out on that question). The figures are still climbing.

“This phenomenon of high temperatures and lots of sun is still prevalent,” said Humberto Fischer, director of AquaChile, which has reported 2.3 million dead salmon – almost 10 percent of his company’s production – at a value of $15 million. “This event hasn’t ended.”

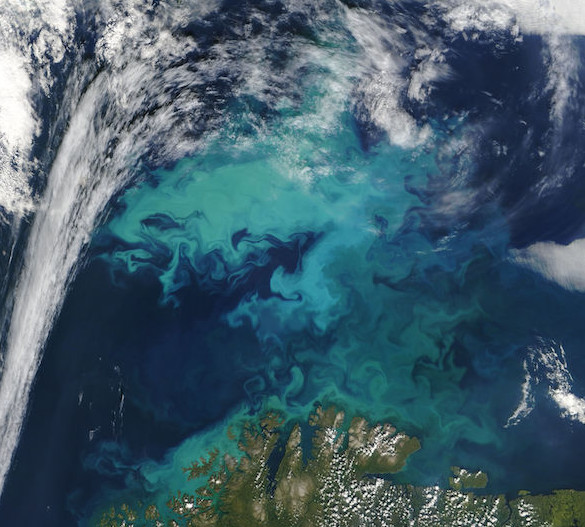

A phytoplankton bloom in the Barents Sea north of Norway in 2004.

Scientists are still trying to understand the exact mechanisms by which the phytoplankton implicated in Chile’s current algal bloom kills fish. There seem to be a few possibilities. First, the rapid proliferation of the photosynthetic plankton can starve the water of oxygen, effectively suffocating the fish. It’s also possible that the massive algal colony is producing neurotoxins like brevetoxin, which can be deadly to fish. Finally, the fish might well be suffocating not solely from oxygen depletion in the surrounding water, but also due to an associated accumulation of mucus on their gills.

Whatever the mechanism, Pseudochattonella verruculosa – which a team of Chilean and Norwegian scientists has identified as responsible for this bloom – and its similar-appearing cousin Chattonella, have historically been implicated in massive fish kills around the world. In 1972, Chattonella reportedly killed 14 million yellowtail in Japan — a loss of millions of dollars. In 1998, it first appeared in the North Sea, and by 2001 it had killed 1,100 tons of salmon. Pseudochattonella verruculosa, which was initially classified in the Chattonella genus, was first detected near Chilean salmon farms in 2004.

In a globalized salmon market, the losses underscore the vulnerabilities facing aquaculture not just in Chile, but around the world. If you eat farmed salmon in the United States, for example, you have almost certainly consumed Chilean salmon. Chile is the world’s second-largest producer of farmed salmon, just behind Norway. The U.S. imports more than 100,000 tons of the fish from Chile every year — about a third of all farmed salmon imported annually.

The current algal bloom is the latest setback in what has been a difficult year for Chile’s salmon farms. Last April, debris from the eruption of Chile’s Calbuco volcano killed an estimated 20 million, mostly juvenile, salmon. In October, Chile levied its largest fine ever on the salmon farming company Los Fiordos for environmental and sanitary violations.

But the biggest shakeup — aside from September’s 8.3 magnitude earthquake — came last July when U.S. retail giant Costco dropped the bulk of its Chilean contracts in favor of Norwegian-bred salmon, citing Chile’s heavy-handed use of antibiotics.

Together, these problems forced Chile’s 2015 salmon production to contract by 16 percent.

Last month, in an effort to warn investors, Chile’s salmon producers reported the gathering algal bloom to the country’s securities and insurance regulators. They also contacted their insurers — though not every company has insurance that will cover losses associated with toxic algae.

“This event will probably be the largest loss to ever hit the aquaculture insurance market,” said Daniel Fairweather, director of aquaculture and fisheries at insurance broker and risk consultancy Willis Towers Watson. Fairweather estimates Chile’s salmon losses from this event could be between 37,000 and 80,000 tons, and that insurers will probably pay out $175 million to those salmon farmers that have purchased biomass insurance coverage. Worldwide, only 3 percent of fish farms are insured, he said. That number is much higher in Chile, but not every company is covered.

That’s ill-advised in a country prone to earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes and red tides, as algal blooms like the one now unfolding are known, said Fairweather. “To be honest, it’s nuts not to get insurance in Chile.”

One of the first reports, filed early this year by salmon producer Multiexport, cited “important” losses of fish, but no firm number was provided. By the end of February, however, the firm Marine Harvest was reporting almost three million dead salmon, while competitors Camanchaca and Blumar had tallied 1.5 million and 110,000 fish, respectively.

How will they get rid of all the dead fish? According to industry publication IntraFish, the current plan is to dump them 60 miles offshore.