New Orleans Knows Mosquitoes

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA – In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the city’s mosquito control board was worried about backyard swimming pools. Officials there had battled the mosquito-borne West Nile virus just three years prior—an outbreak in the state had infected hundreds of residents, killing 24. So they knew, in the wake of the historic hurricane and with temperatures soaring, that evacuated citizens would be returning to neighborhoods dotted with new mosquito breeding factories.

Their solution? Dropping hundreds of Gambusia affinis — a two-inch-long fish more commonly known as the mosquitofish — into thousands of abandoned swimming pools that harbored the Culex mosquito, the genus known to transmit West Nile. Today, 10 years after the storm, these mosquitofish are still out there, consuming scores of mosquito larvae every day in abandoned swimming pools across New Orleans.

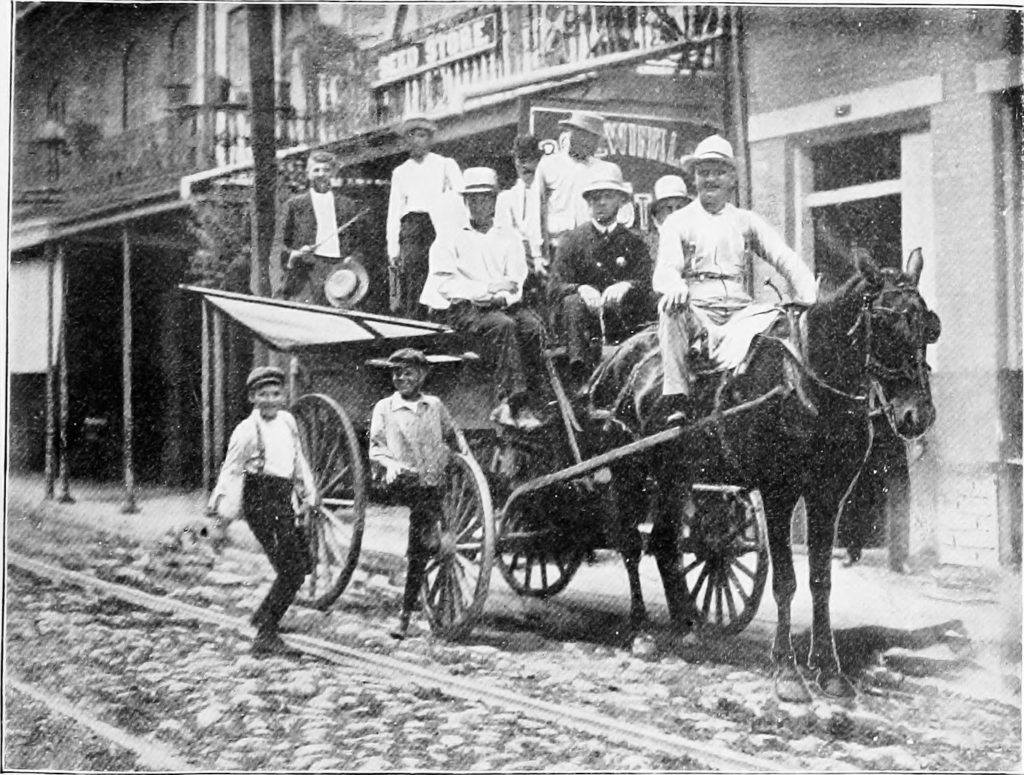

Screening gang about screen a room containing a yellow fever patient, New Orleans, 1905.

To be sure, cases of West Nile in Louisiana did go up after Katrina, according to Tulane researchers, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that these weren’t hurricane-related. Whether or not they’re directly responsible for limiting subsequent bouts of West Nile, the mosquitofish are considered an exemplary use of a biological control that mosquito boards around the country have adopted.

“Mosquitofish are incredibly effective and the practice is fairly widespread in Florida,” says Carlyn Porter, acting director of the mosquito board in Martin County, Florida, which experienced a locally-transmitted dengue outbreak in 2013. Porter and her colleagues have looked at New Orleans’ mosquito control efforts to inform their own. “New Orleans showed us the impact of storm damage and vacant properties on mosquito breeding, which has helped us learn and prepare for similar consequences of future storms.”

Now New Orleans faces a new public health threat: Two mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, have been spreading across the southern United States. They both can carry the dengue, chikungunya and Zika viruses that have infected millions across this hemisphere. The good news: The New Orleans mosquito control board, thanks to its institutional memory, academic partnerships, and a long history of fighting mosquitoes, is arming itself to control the bugs bringing new diseases to our doorstep.

“Aegypti’s been here basically since it came over on ships from Africa and has been with us all along,” says Sarah Michaels, an entomologist at the New Orleans Mosquito, Termite and Rodent Control Board. Over the centuries, the city’s Aedes aegypti mosquitoes have been the source of chikungunya, dengue and yellow fever outbreaks that killed thousands. But these mosquito-borne epidemics eventually stimulated novel mosquito control techniques — like using screens or pouring a layer of oil into standing water to prevent mosquito breeding — and public health awareness campaigns like the 1960s cartoons published by The Times-Picayune newspaper as Louisiana struggled to control mosquitoes.

New Orleans draws on this history, explains Michaels, to tackle new mosquito-borne disease scares. In 2011, after a dengue outbreak in Florida, Michaels and her team drew up a dengue response plan for New Orleans that included testing for both Aedes species at known breeding hotspots like the Bywater and Mid-City neighborhoods and outlining aerial spraying protocols if an outbreak were to occur. In 2014, her team closely followed three cases of chikungunya brought to New Orleans by travelers returning from the Caribbean. They were able to contain that virus.

Given this modern track record, should Zika hitch a ride to the Big Easy on a mosquito — or a human — the city might be better prepared than others to confront the virus.

“We’re lucky,” says Michaels. “We’re in a good position in that we’re ahead of most places.”

Still, pivoting to take on these other mosquito species will mean confronting several challenges. The turnaround time for testing mosquitoes for viruses, for example, is one week, and it involves shipping vials of mosquitoes to Baton Rouge. Aedes mosquitoes also have much smaller ranges and are attracted to different cues than the Culex mosquitoes that control boards across the country have been set up to capture while looking for West Nile.

These hurdles are not unique to New Orleans, points out David Morens, an epidemiologist and senior advisor at the National Institutes of Health. “In the face of these new diseases and fickle new species,” he says, “control boards across the United States will have to learn to adapt to find and control them.”

“It is probably true to say that there is no place in the world with truly effective Aedes control. To a certain extent, these epidemics tend to come and go when they please, and our public health ability to prevent and control them has become limited.”

Which is why control boards need to look at the lessons learned in places like New Orleans to beef up their own mosquito monitoring and control. This comes down to sharing what works and what doesn’t, which is what mosquito experts recently convened to do at the annual meeting of the American Mosquito Control Association.

“Sharing knowledge and experience is key in communicating the complexities of mosquito population dynamics and effective means of control,” says Porter.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Aleszu, here is a paper from that mosquito board’s efforts: http://www.albany.edu/faculty/fboscoe/papers/moise.pdf

Thanks for sharing the paper! Very interesting biological control.

Is there a link somewhere to 1960s Times-Picayune cartoons?

Hi Tim – You bet – and apologies for the oversight. We’ve added the link in the text. Best, -Tom

Mosquito-fish are native to Southeastern and Eastern US, but when introduced to water bodies elsewhere, they either compete destructively with native fish that eat mosquito larvae or they eat the insects that eat mosquito larvae. They are not a panacea for mosquito control. For more information, see http://www.gambusia.net/

Thanks, Ellen. That’s an important point you make. USFWS only granted New Orleans a permit for pools–and not natural waterways–because of this. Your point will definitely be a concern if the fish are proposed as a biological control in regions outside those endemic areas. Interestingly, though, the fish have been tested in places like New Jersey: http://vectorbio.rutgers.edu/outreach/ipm.php